The Marmes Rock Shelter, one of the world’s most exciting archaeological sites, is buried under the waters of Lake Herbert G. West, the reservoir behind Lower Monumental Dam, one of four federal dams on the lower Snake River in southeastern Washington. How the site came to be lost for further research, a loss that occurred literally as the rising water lapped at the boots of scientists working at the site, is another chapter in the inexorable march of progress and economic development that was the rationale for dam-building in the Columbia River Basin.

In the summer of 1965 Roald Fryxell, a geologist with Washington State University’s Laboratory of Anthropology, discovered 9,000-11,000 year-old bones in a dusty cave on a hillside near the confluence of the Palouse and Snake rivers. These were the oldest scientifically documented human remains ever found in North America.

The property was owned by farmer Roland Marmes, hence the name. The cave had been known to local residents for decades; Washington State’s archaeologists first learned of the site from a resident in 1953, but serious excavations did not begin until 1965 when Lower Monumental Dam was under construction. Two other dams were planned farther upstream, and the lower Snake had a number of prehistoric sites that would be lost to flooding. The Marmes site was a high priority, and it did not disappoint Fryxell and his WSU colleague, Richard Daugherty.

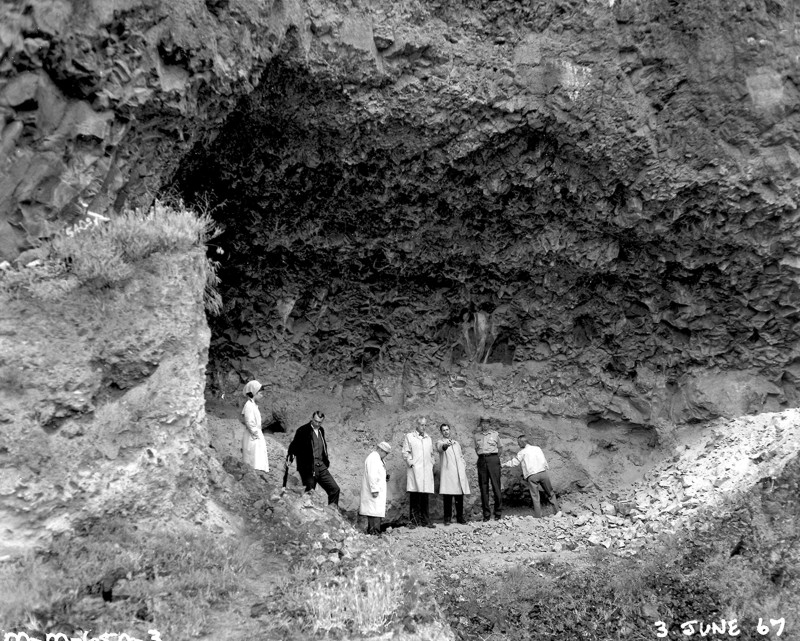

The special significance of the Marmes cave was that it had been used regularly for approximately 10,000 years. There , in a single compact location, was a record of regular use, layer upon layer, just waiting to be peeled away. The odds against finding such a site are astronomical. Fryxell and Daugherty found weapons, artifacts and the bones of animals and humans. They learned that the climate of the region once was much cooler — Marmes yielded the jawbone of an arctic fox — and forested — bones of forest animals including red fox and pine marten also were found. The archaeologists hired more workers, erected a tent city and a laboratory at the site and, by the summer of 1968, had removed some 5,000 cubic yards of material and were continuing to discover items of interest. Construction of Lower Monumental Dam continued at the same time, and soon the spillways at the dam would be closed and the water would rise.

Daugherty appealed to U.S. Sen. Warren Magnuson, an ardent supporter of the lower Snake River dams. Magnuson understood the archaeological importance of the excavation and sought $1.5 million from Congress to build a dike around the Marmes site. The request died in the House of Representatives. Magnuson, undeterred, appealed directly to President Lyndon Johnson. No president ever had ordered protection of an archaeological site, but in October 1968, Johnson did. The Corps of Engineers protested, as did fishery agencies. Construction of the dike would alter the schedule for filling the reservoir behind Lower Monumental Dam and testing its fish passage equipment in advance of the spring 1969 migration of juvenile salmon and steelhead to the ocean. The Corps had planned to begin filling the reservoir in December 1968. Johnson and Magnuson were adamant, however, and the Corps altered its schedule. The dike had to be completed by February 1969 in order to still test the fish passage equipment before the spring migration.

February arrived, and the dike was completed. But it leaked, and it leaked badly. Water poured into the enclosed area at the rate of 45,000 gallons per minute. Pumps were unable to stop the flooding. The Corps opened flood gates at Lower Monumental to lower the reservoir temporarily and allow investigation of the leaking dike. The problem was discovered, but it could not be fixed in advance of the salmon and steelhead migration. The Corps ordered the site abandoned, and the water rose. The dam officially began operation on May 28. Today the cave lies beneath 40 feet of water, enclosed by the ineffective dike.

In their history of the lower Snake River dams, Controversy, Conflict and Compromise: A History of the Lower Snake River Development, written for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, authors Keith Petersen and Mary Reed synopsize public reaction and sentiment about the flooding of the historic site:

Many newspapers throughout the Northwest blamed the [Corps of] engineers for the flooding. But in reality, Marmes was lost by an unfortunate series of events: If only archaeologists had begun excavating earlier. If only Congress had authorized money to construct the dike in the summer of 1968, allowing ample time to plan and build a suitable breakwater. If only Congress had provided funding to dewater the site once it flooded. If only fisheries people had not put so much pressure on the Corps. If only these circumstances had changed, archaeologists might know much more about the early people who came to settle the lower Snake River after the last Missoula flood.

Marmes was a significant loss, but not a fatal a blow to the accumulation of archaeological knowledge about early human habitation of the lower Snake canyon. Dozens of other sites also have been excavated and many significant objects recovered, including a Jefferson peace medal presented to a Palus chief by Lewis and Clark. Marmes simply has an ironic distinction: a treasure chest of knowledge about early human culture in the Northwest that laid undisturbed for thousands of years was lost in a comparative sprint of activity to protect migrating fish and provide hydropower and slackwater navigation.

Read an excellent story about Marmes in the Pacific Magazine of The Seattle Times for Nov. 22, 2017.