The hydroelectric potential of the Columbia River and its tributaries was vast. Viewed from the perspective of the Great Depression the potential appeared limitless, but it was not.

Dams, particularly the huge hydropower projects on the mainstem Columbia, brought inexpensive electricity, industrial growth, irrigation, jobs and industrial expansion to the region from the late 1930s through the 1950s. By then, however, it was evident that the power production potential of the Columbia would be tapped out soon and new sources of electricity would be needed to augment the hydropower supply. The logical choice was thermal power, electricity produced by burning a fossil fuel, such as coal or natural gas, and using the heat to boil water to produce steam to drive turbines. Nuclear power also is thermal power. The uranium reaction releases heat that is used to boil water to make steam.

By the mid-1950s the idea of a hydro-thermal power system for the Northwest was receiving serious consideration. In 1956, the Washington State Power Commission reported that the “use of steam generation in conjunction with hydro plants makes it possible in some cases to increase the firm output of a power system at lesser cost than by construction of new hydroelectric projects or by the use of steam plants alone.” In 1957 the Corps of Engineers’ update of its “308” Review Report on river and dam operations predicted that if demand for electricity continued to grow at the forecasted rate, all economically feasible hydropower dams in the Northwest would be built by 1975, thus bringing to an end the first — hydroelectric — phase of the region’s electric power development. The second — hydro-thermal — phase would add thermal plants to the region’s supply system. The 308 Report also talked about a third phase, in which thermal generation would come to dominate.

The hopeful predictions of rapid regional growth in the federal report did not come true, however, and the effort to meld thermal power, particularly nuclear power, with hydropower in the 1970s and early 1980s was remarkable for its wrong turns, faulty forecasts, management blunders, betrayal of public trust and huge cost overruns that resulted in the largest municipal bond default in United States history to that time.

If this series of events were traced to a single moment, the starting point of a string of events that ultimately would force the region’s electricity consumers to pay debt service on bonds for uncompleted nuclear plants 44 years into the 21st Century, it might well be this: In May 1965 Owen Hurd, managing director of the Washington Public Power Supply System (WPPSS), announced that nuclear power was the resource of the future for the Pacific Northwest.

WPPSS, based in Richland, Washington, near the Hanford Nuclear Reservation, had been organized by 17 public utilities in the state in February 1957 for the purpose of consolidating their assets to build power plants. WPPSS owned and operated the 27.5-megawatt Packwood Dam, completed in 1963 at Packwood Lake on the west side of the Cascade Mountains. In 1962, with the support of the Bonneville Power Administration, WPPSS was selected to build and operate the 800-megawatt Hanford Generating Project at the New Production Reactor (N Reactor) at Hanford, which Congress had authorized in 1958. In May 1965, when the Hanford power plant still was under construction (it would begin generating power in 1966 and continue in operation until 1987) Hurd predicted that all of the new power plants in the Northwest would be nuclear plants by 1985.

Owen Hurd believed in nuclear power, and he was not alone. At the time, there was general agreement among the region’s public utilities that nuclear power was the power of the future. Many Northwest utilities, public and private, touted nuclear power and promoted their own sites for the next nuclear plant.

Owen Hurd also was a believer in public power, and he understood that nuclear plants, typically large and expensive, could not be financed solely by the region’s small public utilities, even by pooling their resources through WPPSS. So he turned to Bonneville, the biggest power supplier and deepest pocket of electricity revenues in the Northwest. And Bonneville was willing to lead the stampede to nuclear power.

Predictions of shortages

In October 1966, the newly appointed administrator of Bonneville, David S. Black, told utility officials meeting in Portland that the agency was “looking toward the region’s very imminent transition into a new era of thermal-electric generation.” Demand for power was growing in the region, Black said. He warned that the region would develop most of the available hydropower sites by 1975, which was just nine years in the future, and therefore would need “at least one million kilowatts of new thermal generation each year thereafter.” He said that without new thermal plants, Bonneville would not be able to meet the demand of its customers after the mid-1980s and would gradually reduce and ultimately halt power sales to privately owned utilities. But Black had a plan, a staggering construction project of new dams and thermal plants, both coal and nuclear, that would result in 32,000 megawatts of new generating capacity over 20 years, huge plants that would take advantage, he said, of economies of scale and solve the region’s growing energy crisis. Supporters were fond of saying nuclear power would be “too cheap to meter.”

All that was lacking was a means of paying for the new plants.

Under federal law, Bonneville could not build its own power plants. Congress considered the matter in 1951 and 1958, but public power agencies were opposed, as they wanted to build and operate their own plants free of competition from the federal government. In 1966 public power remained opposed. So Bonneville came up with a unique financing scheme. Or, more precisely, Bernard Goldhammer, Bonneville’s visionary director of power management, did. In short, Goldhammer adapted the multiple-partners financing plan for the Hanford Generating Project so that Bonneville would underwrite the construction of new thermal plants but not actually own them.

The scheme was called net billing, and it worked like this: a utility customer of Bonneville would agree to buy a portion of the generating capability of a new nuclear plant to be built by the Washington Public Power Supply System and its partners. The Supply System would issue revenue bonds to cover the share. Bonneville would assume the share and credit the utility’s future power purchases by that amount, and then bill the utility for the net difference between the share amount and its actual purchases over time. Hence, “net billing.” Bonneville did not actually buy the shares and so did not actually own the net-billed plants. Net billing relieved utilities of the financial risk of building plants on their own. In essence, money to pay for the WPPSS bonds was supplied by Bonneville through its general wholesale rates — costs and financial risks were spread among all Bonneville customers — and flowed through the Supply System to the bondholders.

By assuming the utilities’ shares, Bonneville also assumed their share of the debt and ensured the revenue bonds would be paid back with revenue from Bonneville’s power sales. As well, because the WPPSS bonds were backed by Bonneville, and thus the United States government, the interest rate was lower than if the bonds had been backed only by WPPSS. In theory, at least, this further reduced the financial risk to the utilities and ratepayers.

Net billing is a complex subject, difficult to describe simply. In a document from the 2014 Integrated Program Review–2 process, Bonneville answered questions posed by Argus Media, including one regarding net billing. Here is how Bonneville described it:

“The net billing agreements obligate the project participants, consisting of numerous public utility districts and municipal and electric cooperative utilities, to pay Energy Northwest a proportionate share of the project's annual costs, including debt service, in accordance with each participant's purchase of project capability. BPA, in turn, is obligated to pay (or credit) the participants identical amounts by reducing amounts the participants owe for power and service purchased from BPA under their power-sales agreements. Even after project termination, such as in the case of Projects 1 and 3 (the construction of the nuclear units was terminated), the obligation for debt service remains until the Energy Northwest nuclear bonds are retired.”

Gary Miller, an employee of Energy Northwest, offered this practical explanation in his 2001 history of the agency, “Energy Northwest: A History of the Washington Public Power Supply System:”

“If a participating utility were obligated to pay $15,000 a month for its share of a WPPSS project’s cost and it owed Bonneville $20,000 a month for wholesale power, it would send BPA a check for $5,000 and the Supply System a check for $15,000.”

That was how the arrangement worked on paper, but in reality utilities did not make separate payments. Bonneville collected the entire amount and sent the Supply System its share. In other words, the utilities took out mortgages with WPPSS and Bonneville made the payments. It’s important to note that the debt incurred by the utilities was not related to the power output, or lack of it, from the three plants but to the debt issued to finance their construction.

Some of Bonneville’s customers utilities balked at net billing because by handing over their shares to Bonneville they handed over management control for constructing and operating the plants — to Bonneville's partner, WPPSS. The management issue eventually proved to be critical, as Bonneville ultimately was responsible for the shares it acquired — repaying the debt — even if the plants were not built. In order to avoid actually subsidizing construction, Bonneville would have to raise the rates it charged its customers if the cost of a net-billed plant escalated. Potential rate increases aside, Bonneville liked net-billing and so did its utility customers. It kept Bonneville in charge of the region’s electricity supply, and it allowed the utilities to build their own plants.

In October 1968, Bonneville and its advisory committee that represented the agency’s 108 customers, the Joint Power Planning Council, unveiled their vision of the future: The Hydro-Thermal Power Program. Together, Bonneville and its customers would build 21,400 megawatts of thermal power — two coal-fired plants and 20 nuclear plants — and 20,000 megawatts of new hydropower between 1971 and 1990, at an estimated cost of $15 billion, to supplement the Columbia River power system. That same year, the utilities decided the first projects would be the twin coal-fired plants at Centralia, Washington (these were completed in 1971 and 1972) and the Trojan nuclear plant on the Columbia River near St. Helens, Oregon (completed in 1976; closed in 1993). Public utilities would own 33 percent of each project. In 1969, it was decided that Phase I would include a total of seven projects: the two Centralia coal plants and five nuclear plants that would be built over a period of 10 years. Owen Hurd wanted WPPSS to build at least one of the nuclear plants, and he was supported by the Public Power Council, which represented Bonneville’s public utility customers.

In Washington, D.C., at this time Bonneville was lobbying for approval of the net-billing concept. A new administrator, H.R. Richmond, repeated the now-familiar warnings of impending power shortages as justification for the new plants. He spoke of brownouts, blackouts and power-rationing if new plants were not built. He said demand for power would overtake Bonneville’s supply sometime between 1971 and 1975. He estimated the seven Phase I plants would cost only $1.7 billion total, which equated to a power cost from the plants of one-half of one cent per kilowatt-hour. Even in 1970, that was very inexpensive electricity.

Congress approved the concept and authorized Bonneville to use net billing for all of the Phase I plants. Contracts fell into place quickly. Bonneville and 94 utilities signed contracts for the 1,100-megawatt WPPSS Project 2, at Hanford, on Jan. 4, 1971. Bonneville and 104 utilities signed contracts for the 1,250-megawatt WPPSS Project 1, also as Hanford, on Feb. 6, 1973. Bonneville and 103 utilities signed contracts for WPPSS Project 3, at Satsop, Washington, west of the Cascades in Grays Harbor County, on Sept. 25, 1973 (investor-owned utilities signed up for 30 percent of the output of this plant). These three WPPSS projects, along with the Centralia coal plants and the Trojan nuclear plant, were the six net-billed projects of Phase I (a fifth nuclear plant never got off the drawing board).

Cost overruns and opposition

Net billing proved to be problematic. Publicly, net billing was perceived as a federal subsidy for the WPPSS nuclear plants, although it wasn’t intended to be. Bonneville intended net billing as a creative way to avoid federal ownership of power plants and spread the financial risk of new construction among a broad base of utilities. Ratepayers were advised that the nuclear plants would be an inexpensive way to meet future demand for power. The message from Bonneville was: “Trust us.” But Bonneville and its utility partners hadn’t planned on the fact that ratepayers might not support construction of nuclear power plants as their costs rose. And the costs did rise: ultimately by about 600 percent.

Almost immediately after the utilities signed contracts with Bonneville, cost overruns began to plague the construction effort. Bonneville, as the backer of the plants, soon had to raise its rates to cover the rising costs, something it had done only once (in 1965) since the agency was created in 1938. The 1974 rate increase was tied directly to cost-overruns at the net-billed plants. With the increase, Bonneville’s residential rate was .325-cent per kilowatt-hour, or about one-third of a cent and still far below the national average. Public support for the Phase I plants began to wane as WPPSS began what would become periodic announcements of new — and always higher — cost estimates for the plants.

In August 1972, the Internal Revenue Service issued regulations that killed net-billing, at least for the future. The regulations prohibited government tax-exempt financing of power plants from which the government would buy more than 25 percent of the output. The IRS allowed net-billing to continue for the Phase I plants because it already was in place. But the new regulations meant future projects of the Hydro-Thermal Power Program would have to be financed differently. At this time, Bonneville was close to exhausting its net-billing capacity, as the cost of the nuclear power that Bonneville would buy from the plants might become greater than the revenue Bonneville collected from its customer utilities.

This caused Bonneville to rethink its role as the region’s central power authority and long-term power-planning agency. But Bonneville still supported the construction of more thermal plants, particularly nuclear plants, to supplement the hydropower supply in the long term. And if Bonneville could not underwrite new plants through net billing, then its utility customers would have to underwrite new plants themselves. After all, the impending power-supply crisis still loomed and new power would be needed, or so Bonneville believed.

The Treaty of Seattle

Bonneville’s had an ally in the Public Power Council (PPC), which had issued a request in May 1973 that WPPSS build a fourth nuclear plant financed collectively by all of the region’s public utilities. In November, Public Power Council Manager Ken Dyer said at a PPC membership meeting that utilities that did not participate in Plant 4 “may find themselves without ability to meet their load growth after the date of insufficiency.” The next month, Bonneville developed a financing scheme for this plant and others that would be built in the future. Bonneville labeled the plan Phase II of the Hydro-Thermal Power Program. Informally, the plan was known as the Treaty of Seattle, in honor of the city where it was negotiated, and also in recognition of the fact that the WPPSS cost overruns at the Phase I plants were fraying nerves and souring relations among the region’s utilities.

As envisioned, Phase II would include 1,800 megawatts of coal-fired plants, 5,800 megawatts of nuclear power and 3,700 megawatts of new hydropower. The construction would include WPPSS Plant 4 — the one proposed by the Public Power Council — plus three other nuclear plants, four coal plants and power from the Hanford Generating Project, which WPPSS operated. Another of the new nuclear plants was Plant 5, which the WPPSS board of directors agreed to build on May 10, 1974, again in response to a request from the Public Power Council. Where possible, new plants should be twins of existing plants, the Public Power Council advised, and WPPSS agreed.

Ultimately, construction would begin on only two of the envisioned Phase II nuclear plants, but they would be twins of two Phase I plants already under construction. WPPSS Project 5 would be a twin of Project 3 at Satsop, and Project 4 would be a twin of Project 1 at Hanford. Plants 4 and 5 were to be completed by 1982.

Phase II represented a big change for the region and for Bonneville. Unlike Phase I, the utilities, not Bonneville, would bear the financial risk of the new plants, and Bonneville would only buy power from the plants and resell it to other utilities. The owners of the plants were free to sell their power to anyone. As well, speculation that Bonneville might be able to provide financial backing for the plants even without net-billing made the decision to participate a little easier.

With Bonneville continuing to predict looming power shortages, the early 1970s were marked by a frenzy of power-project planning. Investor-owned utilities planned their own new projects. Public utilities wanted to be players, too, and they rallied around WPPSS and the Public Power Council. They envisioned Plants 4 and 5, totaling 2,500 megawatts of generating capacity, as their contribution to the region’s future power supply. In 1974, WPPSS agreed to build them.

Faulty demand forecasting

In retrospect, one has to wonder why WPPSS agreed. As well, why did Northwest utilities rush to embrace nuclear power at a time when the rest of the country was beginning to back away from it? In 1974, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission counted 14 nuclear plants elsewhere in the country that had been proposed for construction and then canceled, and by 1976 the number stood at 26. WPPSS Project 2 had been under construction for two years in 1974, and it was plagued by cost overruns. So why did 88 public utilities sign contracts to build WPPSS projects 4 and 5?

According to reporter Howard Gleckman, who wrote a series of articles about WPPSS in the Bond Buyer newsletter in 1984, the utilities were convinced by their consulting engineers that the plants were feasible and cost-effective, based on figures provided by WPPSS. Also, some of the participants simply wanted to build their own, large power plants. They wanted to be players in the regional power game. They wanted to reduce Bonneville’s control over the regional power system. They were afraid of losing customers to investor-owned utilities if they did not build their own plants and get into the power-sales business. And of course, they believed their own forecasts that the region would need the power in the future.

Warnings of future shortages had been the drumbeat behind the region’s crash construction program for at least 10 years by 1974. And the utilities didn’t have to take Bonneville’s word for it. In the early 1970s, the Pacific Northwest Utilities Conference Committee (PNUCC), a consortium of Northwest utilities, compiled electricity forecasts for the region from its members, whose forecasting abilities varied from utility to utility. Some relied on Bonneville, some relied on consultants, some relied on their staffs, and some simply guessed. There was a certain circularity in this arrangement: Bonneville did forecasting for many of its customer utilities — these were small and lacked demand forecasting expertise, these utilities then reported their forecasts to PNUCC, and PNUCC compiled the forecasts and reported the results to Bonneville.

Additionally, demand forecasting in the early 1970s was pretty much straight-line thinking. If power demand had increased at a certain rate over the last two or three years, it would continue at the same rate in the future. But what if the economy soured? And what about the region’s nascent environmental ethic, which had played such an important role during the 1960s in the fight over hydroelectric dams in Hells Canyon and during the Oil Embargo of 1973. What if people simply refused to pay for nuclear power, particularly if its cost continued to rise? In general, the region’s utilities believed electricity rates were so low that people would absorb rate increases and not reduce their consumption. This would prove to be a big miscalculation.

In hindsight, PNUCC’s energy-demand forecasts of the 1970s, the forecasts that assured the region’s utilities that new power plants were necessary, were wildly optimistic. The PNUCC forecasts would prove to be too high by as much as 600 to 1,600 megawatts per year. That’s a difference of between one-half and 1.5 nuclear plants. At the same time, the Public Power Council continued to push its members to sign up for shares of Projects 4 and 5. Bonneville helped. In November 1974, Administrator Don Hodel wrote to Bonneville’s utility customers advising them to sign up for power from Projects 4 and 5, and quickly: “Any utility which needs additional power resources in the mid-1980s will need to enter the participants’ agreements with WPPSS at this time,” Hodel wrote. In 1975, Hodel began warning his customers that without the new plants Bonneville might not be able to meet its firm-load requirements by the mid-1980s. In a speech to the Portland City Club on July 11, 1975, Hodel chastised the critics of nuclear power:

This new environmental movement is on a collision course with the growing demand for energy . . it has fallen into the hands of a small, arrogant faction which has dedicated itself to bringing our society to a halt. They are the anti-producers, and anti-achievers. The doctrine they preach is that of scarcity and self-denial. I call this faction the Prophets of Shortage.

Hodel assistant Dan Schausten, who drafted much of that speech, later told author Gene Tollefson that Hodel lived to regret the name-calling because it created a cleavage between Bonneville and its critics rather than a new dialogue. Schausten maintained this was contrary to Hodel’s usual style with people, but Hodel also was known to be quite impatient with those who did not see the world the way he did. At any rate, his message to the utilities was terse and unwavering: sign up for nuclear power or face shortages.

On June 24, 1976, Hodel issued a “notice of insufficiency” to Bonneville’s customers, declaring that if Bonneville did not acquire new power resources it would not be able to meet the future growth requirements of its firm-power utility customers by the mid-1980s. If it was a threat, it was not lost on the customers. Some of Bonneville’s larger customers would sue the agency in 1982, charging they were “seduced” into supporting the plants. But in truth, fears of future power shortages were widespread in the mid to late 1970s. PNUCC, Bonneville and the Public Power Council, whose expertise really was not questioned at the time, all were predicting future shortages. In his Bond Buyer articles, Gleckman quotes Robert McKinney, general manager of Cowlitz Public Utility District in Longview, Washington, who had said at the time Bonneville issued its notice of insufficiency: “We were only in [Projects 4 and 5] to avert a regional power shortage.” The hand of Bonneville was heavy on the utilities to join up. Gleckman quotes an unnamed utility official who commented, in retrospect: “Don’t you understand? Bonneville was the Godfather. They made the offer you couldn’t refuse.”

While it could be argued that inaccurate demand forecasts and growing public opposition to nuclear power, combined with cost overruns at the WPPSS plants that were under construction in the 1970s, doomed Projects 4 and 5, it is more likely that the beginning of the end came in the form of a lawsuit aimed at Bonneville. The lawsuit challenged the plants under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), which Congress had approved in 1969. And it wasn’t environmentalists or utilities that sued Bonneville. It was the Port of Astoria.

Legal challenges

Alumax Pacific Corporation had proposed to build a smelter at Astoria, and many people there supported it. But many others didn’t, including environmentalists and the Oregon Environmental Quality Commission, which had concerns about the unavoidable fluoride emissions from an aluminum smelter and their impact on the Youngs Bay Estuary adjacent to the proposed smelter site. Alumax decided to build the plant in Umatilla County in eastern Oregon rather than face the local opposition. At the same time, Alumax signed a contract with Bonneville for power. Hoping to keep the smelter in Astoria, the Port of Astoria sued Bonneville under NEPA, which requires an environmental impact statement before proceeding with major federal decisions that affect the environment. In August 1975, U.S. District Judge Otto Skopil sided with the Port and the Natural Resources Defense Council, which had filed a similar NEPA lawsuit to block Phase II, and ordered Bonneville to complete an environmental impact statement (EIS) on its power sales contract with Alumax for the Umatilla site. Bonneville complied, but the focus of the EIS was much broader than the contract with Alumax, addressing Bonneville's role in regional power supply. It took five years, until 1980, to complete. This effectively killed Phase II because the utilities were anxious to build plants 4 and 5 and would not wait for Bonneville to guarantee the debt through long-term power sales contracts.

Meanwhile, assuming Phase II would go ahead Bonneville worked in Congress to win authority to buy the output of plants 4 and 5. The Columbia River Transmission Act of 1974 gave Bonneville the authority to spend its revenues on transmission system upgrades and also to borrow up to $1.25 billion from the federal Treasury for that purpose. In 1976, at about the same time that the public utilities agreed to back the debt of plants 4 and 5, PNUCC proposed legislation that would have given Bonneville authority to buy the output of the two plants directly. It was introduced in the Senate in September 1977 by Henry Jackson of Washington. Ironically, the bill was opposed by the senator’s hometown utility, the Snohomish County Public Utility District, whose manager thought the bill would force the region’s public utilities to shoulder too much of the cost of future plants, including plants 4 and 5. This opposition, and the growing anti-nuclear settlement, doomed the PNUCC bill.

There were other problems, as well. In 1976, the Seattle City Council authorized the municipal utility, City Light, to participate in an interim agreement authorizing a $100 million bond sale to begin construction of plants 4 and 5. It was not a commitment to pay for the plants — not yet, at least, but it would have given Seattle a 10-percent share of their output. The Washington Environmental Council sued the city to force an environmental impact statement. The two parties negotiated a deal, however, in which the environmental group would drop the suit if the city would commission an independent study of Seattle’s future demand for energy. The dispute was not only about nuclear power, it was about power-demand forecasting. It was evident that many people in the region did not trust or accept PNUCC’s view of the future, which predicted annual demand growth of nearly 5 percent per year in the region far into the future.

The conservation revolution

The Seattle study, called Energy 1990, demonstrated that energy conservation could reduce Seattle’s demand for power and, therefore, reduce the number of new power plants that would have to be built in the future. Importantly, the study also predicted that people would use less electricity as its cost increased. This, too, was a radical notion, as PNUCC and the utilities simply assumed that people would pay for electricity regardless of its cost. After all, the region enjoyed the lowest-cost electricity in the nation, and the utilities assumed that a few extra pennies per kilowatt-hour would not be noticed. However, given how low power rates were in the Northwest at the time, those few extra pennies per kilowatt-hour would mean a huge percentage increase in electricity bills. Certainly, ratepayers would have noticed.

Energy 1990 was made public in January 1976. In July, after contentious public hearings, the City Council rejected City Light’s participation in plants 4 and 5, convinced by the Energy 1990 study that Seattle could meet its future energy needs largely through conservation and certainly without plants 4 and 5.

The vote was a turning point. Many perceived the vote as anti-nuclear, many perceived it as anti-development, and many perceived it for what it arguably really was — a careful decision based on Seattle’s specific future energy needs and potential to reduce demand for power through conservation. For WPPSS, it was another blow.

Meanwhile, Plant 2 continued to suffer cost overruns. In February 1976, a month after the public release of Energy 1990, WPPSS fired its prime contractor at Plant 2 because of the continuing construction cost overruns. It could be argued that if the Seattle City Council’s vote on plants 4 and 5 was not a sort of referendum on nuclear power, it was at least informed by the developing crisis at WPPSS. And the vote didn’t dissuade other participants in Plants 4 and 5; in July 1976, 88 public utilities signed agreements to finance the plants. It was the same month Seattle decided not to participate. WPPSS told the participants that plants 4 and 5 would cost a total of $2.366 billion — $1.095 billion for Plant 4, planned for completion by March 1982, and $1.271 billion for Plant 5, planned for completion by April 1984. Just one month later, WPPSS announced the first cost increase for the two plants — a whopping $540 million — and blamed construction delays and cost increases that already had developed, as well as unanticipated “cost contingencies.” The participants were concerned, as were their customers. Key staffers at Bonneville were concerned that WPPSS might be overextended.

The Energy 1990 study made public a sentiment that had been developing for several years in the Northwest, that conservation could significantly reduce the region’s future need for power and do so at a cost less than the cost of new nuclear plants. That is, why build thermal plants when conservation costs the same or less, uses no fuel and, therefore, doesn’t pollute? Others weighed in with their own forecasts of declining future energy demand, including the Natural Resources Defense Council, The Oregon Department of Energy and the Northwest Energy Policy Project, the latter on behalf of the region’s governors. At about the same time, PNUCC adjusted its own forecast of future demand downward by a full percentage point, from annual growth rates of 4.9 percent to 3.9 percent. This still was much higher than the other forecasts, however.

Beginning of the end

It is difficult to pinpoint a precise event that signaled the beginning of the end for the WPPSS plants. All but Plant 2 ultimately were canceled during construction. However, the events of 1976 were critical. It is not an exaggeration to say that the region was in turmoil about its energy future. WPPSS, the Public Power Council and their two law firms were trying to ensure that the participants’ agreements for plants 4 and 5 were legal, but neither WPPSS nor Bonneville would allow a court test of the “take-or-pay” style of contracts for the plants (this means the utilities were obligated to pay for the plants even if they were not completed or their energy not needed) before the contracts were signed, as had been done in other states. Bonneville, PNUCC and the Public Power Council continued to warn that the plants were needed to avoid future power shortages, but the reports on conservation were widely perceived as warnings that they were not. WPPSS, meanwhile, needed signed contracts in order to arrange financing.

The 88 participants had signed up for 100 percent of Plant 4 and 90 percent of Plant 5, with the remaining 10 percent sold to Pacific Power & Light Company, but the same month the agreements were signed, July 1976, a consultant completed a study for Bonneville that seemed to confirm that the plants were not needed. It was a bombshell.

Bonneville paid Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, an engineering firm, to study the region’s energy conservation potential, and the firm reported — actually just before the deadline for the 88 utilities to sign the contracts for plants 4 and 5 — that conservation would be as much as six times less expensive than building an equivalent amount of nuclear power. Bonneville allowed the contracts to be signed and sat on the Skidmore/Owings report until October, even though its conclusions had been leaked to reporters shortly after it was completed. Bonneville then attacked the study as “full of holes,” and said the nuclear plants would be needed even if the region undertook an aggressive conservation program.

Public opinion was split over the need for the plants and the need for nuclear power generally; public and private utilities expressed concern about future power costs and supplies. The construction costs of plants 1, 2 and 3 continued to increase. In the midst of this chaos, WPPSS forged ahead, issuing the first long-term bonds for plants 4 and 5 in February 1977, despite a problem that ultimately would bring down the plants. The problem was that the time, WPPSS’ lawyers had been able to review and certify the legality of only 72 of the 88 participant contracts. The remaining participants, who collectively represented 4 percent of the total subscription, might have legal problems with the contracts, the lawyers determined. But WPPSS assumed the shares could be absorbed by the other participants if necessary, as their contracts obligated them to pick up as much as 25 percent of the total power from the two plants if other participants had to drop out.

But WPPSS was wrong. Once construction got under way at plants 4 and 5, WPPSS almost immediately suffered the same construction cost escalations and management problems that were plaguing the other plants. As WPPSS’ financial woes mounted and WPPSS responded by issuing more bonds to cover its increasing costs, the participants revolted. They refused to obligate their ratepayers to the ever-growing costs of nuclear plants that were looking more and more like black holes. They sued WPPSS to get out of their contracts, and courts in Idaho, Oregon and Wyoming sided with them. The death blow, however, came in June 1983, when the Washington Supreme Court ruled that public utilities in the state, which owned nearly all of the potential output of the two plants, were not obligated to repay the debt because they did not have the authority in state law to sign the contracts in the first place. Less than two months later, WPPSS defaulted on $2.25 billion in bonds for the plants. That was just the principal amount. Interest added $5 billion.

Faulty financing

At the root of the financial meltdown was WPPSS’ unique history of borrowing money to pay for construction. WPPSS had to increase its borrowing, of course, as cost overruns mounted at the plants. The cost overruns occurred for a number of reasons, but a major factor was the design/build nature of the construction. The plants were designed as they were built, which worked well as long as it wasn’t necessary to stop and repair or change something that already had been built. But that is precisely what happened, time and time again. The biggest problem WPPSS faced, though, was financing and the cost of money. Interest rates were at record high levels in the late 1970s, and WPPSS decided to capitalize the debt, which meant it would borrow money for repayment later rather than directly charge ratepayers of the participating utilities while the plants were under construction. This made the utilities happy because it pushed payments into the future, but it proved to be a nightmare for WPPSS. As its costs rose, WPPSS was forced to borrow money to pay interest on the bonds it had sold earlier. WPPSS sold its last bonds for plants 4 and 5 in March 1981, five years before construction was expected to be completed. By that time, 45 cents of every dollar WPPSS borrowed went to capitalize its interest costs. In July 1981, WPPSS learned that its bankers no longer would authorize borrowing unless the participants agreed to help pay the interest costs, and they refused.

Ultimately, the cost of the WPPSS nuclear plants ballooned to far beyond original estimates. Plant 2, planned at $465 million, cost $3.2 billion. Estimates of the costs of the other projects shot up over time, as well: Plant 1, from $1 billion to $4.3 billion; Plant 3, from $1.4 billion to $4.6 billion; Plant 4, from $1.4 billion to $3.6 billion; and Plant 5, from $1.3 billion to a staggering $6.2 billion. In 1975, WPPSS had estimated the total cost of the five plants at $5 billion. In 1981, it was $24 billion. The rapidly escalating costs led Bonneville to raise its rates to cover its WPPSS-related costs. Rates went up 107 percent in December 1979, 61 percent in July 1981, 54 percent in October 1982 and 22 percent in November 1983. Using the 1979 rates as a base, the cumulative increase over just four years was 526 percent.

Congress steps in

The cost overruns; the cost of money; the practice of capitalizing interest, which helped its member utilities avoid raising rates; the increasing public acceptance of energy conservation as an alternative to generation; all of these influenced the future of WPPSS and the region’s energy supply in the late 1970s. The legislation that PNUCC proposed in 1976, legislation that would have given Bonneville authority to acquire the output of plants 4 and 5, was revised in light of these concerns to become the Northwest Power Act of 1980, which still allowed Bonneville to acquire the nuclear energy, but only with approval of the Northwest Power Planning Council (later renamed the Northwest Power and Conservation Council), which the Act created, and only after Bonneville proved to the satisfaction of the Council that it had acquired other less-expensive resources, particularly cost-effective conservation, first.

The cost-effectiveness test showed that nuclear power was much less cost-effective than conservation in the Northwest. In fact, the Act listed generating and conservation resources by priority for future acquisition by Bonneville, and nuclear was lumped with traditional coal-fired power plants at the bottom of the list.

Meltdown

In 1981, the nuclear dream clearly was turning to nightmare. WPPSS continued to borrow money to finance construction of plants 1, 2 and 3, but at high interest rates — more than 10 percent — and with increasingly lower bond ratings, a reflection of Wall Street’s wariness. The rate-paying public, like many financial analysts, was increasingly skeptical. Electricity usage was going down in the region, not up as the utilities had predicted. By October, even Bonneville had decided, informally, at least, that plants 4 and 5 would not be needed until the 1990s. Increasingly, the public saw the WPPSS plants as extraordinarily expensive and unnecessary.

In the summer of 1981, a citizens’ ratepayer group, Don’t Bankrupt Washington, filed enough petitions in Olympia, the state capital, to place an initiative on the November ballot. The initiative would require a public vote on financing new large power plants, including the WPPSS plants. It was approved by a wide margin. Interestingly, the public opposition was not so much to nuclear power per se, but to the mismanagement and economic chaos that WPPSS, Bonneville and its utility partners created.

In May 1981, having determined it would have to borrow $3 billion to keep plants 4 and 5 alive, and realizing it probably could not borrow that much, WPPSS imposed a one-year moratorium on construction of the two plants. The participants were shocked, not the least because they already were into the plants for more $2.25 billion. Despite attempts to keep the plants alive through financing mechanisms that would delay construction but not end it, WPPSS officially abandoned the plants on January 22, 1982. Courts in all four Northwest states took up the matter, ultimately ruling that the utilities did not have to pay. WPPSS defaulted on the bonds for plants 4 and 5 in August 1983, following the Washington Supreme Court decision, when WPPSS was unable to pay the debt as ordered by Chemical Bank of New York, the bond trustee. Chemical Bank sued WPPSS on behalf of the bondholders and, following the court decisions discussed above, a settlement was reached in 1989.

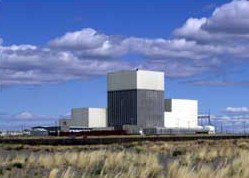

Meanwhile, courts also upheld the net-billing contracts for Plants 1, 2 and 3. But the plants were not needed, at least not right away, and their costs continued to rise. WPPSS and Bonneville suspended construction at Plant 1 in May 1982 when it was 65 percent complete, and at Plant 3 in July 1983 when it was 76 percent complete. Bonneville continued to pay the costs of keeping the plants in mothballs, as it was termed at the time, but both plants finally were terminated in May 1994. Plant 2, with 1,216 megawatts of generating capacity, was completed in 1984 and continues to operate. Today it is called the Columbia Generating Station.

Thus in 1983, 18 years after Owen Hurd envisioned an energy future for the Northwest where nuclear power electrons and hydropower electrons would mix and be sold to consumers at rates so low they would be the envy of the nation, the future was entirely different: the largest municipal bond default in history; only one of five nuclear plants completed — in addition, of course, to the net-billed (and at the time non-operating) Trojan Nuclear Plant from Phase 1; cost overruns that boosted the price of the five WPPSS plants by more than 400 percent; and Bonneville’s debt for plants 1, 2 and 3 — 1 and 3 never completed — that will not be paid off until 2044 (when Plant 2 — the Columbia Generating Station — debt is retired).

World events also played a role in the downfall of the Hydro-Thermal Power Program, at least in terms of public perception. The Arab oil embargo of 1974 was a fresh memory in the late 1970s, and while the concept of energy self-sufficiency was generally accepted — indeed, it was the nation’s policy following the oil embargo — there also were concerns that self-sufficiency should not be achieved at any cost. Installing energy conservation measures was faster and less expensive than building nuclear power plants, and conservation did not depend on any foreign country, utility, coal mine or technology for its fuel. Conservation would not meet all of the region’s future energy needs, but it could delay the construction of new power plants. It was a technology that could provide breathing room for careful decision-making and demand forecasting, a much different approach than the impending-doom drive of the 1970s to build the WPPSS plants.

Historian Richard White, in his 1996 book The Organic Machine, quotes an unnamed Bonneville official commenting on the WPPSS plants: “No one anticipated how hard it would be to build those turkeys.” White comments: “WPPSS was an astonishing failure, an amazing exercise in irresponsibility. But this was the 1980s, and at certain levels of American society, there was apparently no such thing as responsibility for failure. Donald Hodel, the head of the BPA, having left the agency in financial shambles and the power system in chaos, went on to become Secretary of Energy in the Reagan administration.”

Since then, WPPSS has evolved with a new name, Energy Northwest, and new leadership, and the Columbia Generating Station has continued to be an integral part of the region’s power supply. The plant produces on average about 3 percent of the electricity generated in the Northwest and accounts for about 12 percent of the electricity marketed by Bonneville, which purchases the plant’s entire output. In a December 2013 letter to employees, Energy Northwest Chief Executive Officer Mark Reddemann wrote: “The new year brings a good deal of good news with it – Columbia Generating Station moved into the top quartile for industry performance, [and] we surpassed the safety milestone of 10 million hours with no lost-time injuries…”

But controversy continues to dog the region’s only operating nuclear plant. Also in December 2013 two reports — one commissioned by the Oregon and Washington chapters of Physicians for Social Responsibility (PSR) and the other commissioned by Energy Northwest — arrived at starkly opposite conclusions about the future costs of the plant.

Portland-based energy consultant Robert McCullough produced the report issued by PSR, which concludes that power from CGS is significantly more expensive than power from other sources. According to the report, if Bonneville had purchased an amount of electricity equal to the CGS output in Fiscal Year 2013 from the wholesale market rather than from CGS the cost would have been more than $200 million less, and continuing to rely on market purchases until the end of its anticipated life in 2043 would save at least $1.7 billion. This report recommends that CGS be decommissioned beginning in 2015.

The other report, prepared by Cambridge Energy Research Associates of Cambridge, Mass., concludes that the plant is economical to operate. This report finds that the continued operation of CGS will save consumers $1.6 billion over that same timeframe, compared to the lowest-cost alternative of closing the plant and replacing its output with a natural gas-fired power plant.

Clearly, the two studies were prepared by experts and assess an important resource in the Northwest power supply. The fact that they arrive at polar opposite conclusions is a puzzle but also is an important issue for the region. Independent analysis of future resource costs is critical to making the best decisions about future sources of electricity. There are uncertainties on both sides of the issue, such as the future cost and performance of CGS, safety considerations of nuclear power, and costs of alternative power supplies.

The two sides — McCullough criticizing CGS and Brent Ridge of Energy Northwest defending it — continued their disagreements in a series of opinion pieces in The Oregonian newspaper of Portland into the summer of 2016.

Meanwhile, Bonneville continues to pay for the three plants – Columbia Generating Station and plants 1 and 2. The 2020 debt service payment for all three plants (principal and interest total) is $591,634,160.88. Of that amount, $87,002,040.18 is for the two partially built, never-completed plants. The total paid for all three plants since 1978 is more than $2 billion. Bonneville has refinanced its nuclear debt several times, which has the effect of freeing up space under its federal borrowing cap but also pushing the final payoff dates farther into the future. As of November 2019, the total remaining debt is $6,681,952,912. Of this, $1,083,530,438 is for Plant 1 (principal and interest combined), and $1,246,504,736 is for Plant 3. The final payment for the debt on plants 1 and 3 currently is in 2028; the debt on Plant 2, the Columbia Generating Station, continues to 2044.

From 2019 through early 2022, the Council is revising its Northwest Power Plan in a public process, which the Council does every five years. The Council’s responsibility in the power plan is to forecast demand for the next 20 years and develop a least-cost resource strategy to meet that demand, with highest priority going to energy efficiency, then cost-effective renewable resources. Bonneville implements the Council's power plan.

In February 2016, the Council completed work on the Seventh Northwest Power Plan. The resource strategy is heavy on energy efficiency and light on thermal power. The strategy calls for developing about 4,500 average megawatts of new efficiency by 2035, acquiring demand response resources to meet extreme winter and summer peak loads when needed, and using existing natural gas-fired generators to replace three coal-fired power plants in the region as they retire between 2020 and 2026.

New nuclear power is not in the mix.

However, in Chapter 3, Resource strategy, of the plan the Council looks to the future and encourages the region to expand its resource alternatives by exploring additional sources of renewable energy, especially technologies that can provide both energy and winter capacity, improved regional transmission, new conservation technologies, new energy-storage techniques, smart-grid technologies, and demand-response resources, and new or advanced low-carbon generating technologies, including advanced nuclear energy. Elsewhere in that chapter, the Council notes that currently it is not possible to entirely eliminate carbon dioxide emissions from the power system without the development and deployment of nuclear power and/or emerging technologies for both energy efficiency and power generation that do not emit carbon dioxide. Experiments with modular nuclear plants have been under way since at least the early 2000s, but that technology, in which small nuclear plants, or modules, could be connected to generate larger amounts of electricity, has not been proven to be available and cost-effective at utility scale.

Yet.