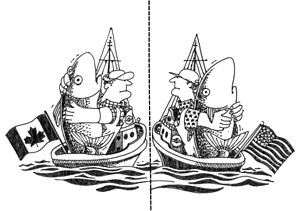

Salmon spawn in rivers from California to Alaska, but in the ocean they mix and become, in essence, a common resource. While political jurisdictions can regulate salmon harvest in their own waters, it impossible to regulate the capture of one jurisdiction’s fish as opposed to another’s in the ocean. For decades, this led to overfishing of some stocks in the ocean and tensions among the state, provincial and federal governments of the United States and Canada.

In 1985, the two countries signed the Pacific Salmon Treaty, which sought to limit harvest of Columbia River fish in Canada and Alaska, and harvest of Fraser River fish in United States waters. The treaty also committed the two countries to enhance their salmon stocks through improvements in the freshwater spawning and rearing habitat. It was not the first treaty the two countries signed regarding harvest of their west-coast salmon stocks, but it was the most comprehensive. In 1930, the two countries signed the Fraser River Convention, which divided the harvest of Fraser River salmon equally among U.S. and Canadian fishers. The Fraser drainage is entirely within British Columbia, but it flows into salt water at Vancouver, and the two countries had long-established fisheries in the border areas between Washington, British Columbia and Alaska.

In the 1970s, both countries extended their fisheries management from three miles to 200 miles off their coasts and attempted to strengthen regulation of cross-border harvests. The two countries signed a draft salmon treaty in 1982, which was ratified as the Pacific Salmon Treaty in 1985. Two key elements of the treaty are to 1) conserve salmon by preventing overharvest and providing for optimal production and 2) share the harvest benefits to the extent that each country contributes salmon to the fisheries. “State of origin” principles would have limited harvest of a country’s fish to the Exclusive Economic Zone of that country, but the Pacific Salmon Treaty allows the harvest of one country’s salmon by the other country and commits the countries to share information on fish production and run sizes. The treaty also created the Pacific Salmon Commission to manage provisions of the treaty.

The Commission, based in Vancouver, B.C., has struggled with one of the significant disagreements that led to the treaty and which was not fully resolved by it — overharvest by one country of the other country’s fish. Salmon from the Columbia River are harvested in great numbers by Canadian fishers off the west coast of Vancouver Island, and salmon from British Columbia are harvested in great numbers by fishers in Alaskan waters, as are Columbia River fish. This is a separate issue that pits Alaska against the Pacific Northwest states. In the Treaty, the two countries commit to consider reducing interceptions of each other’s fish, but the Treaty also discourages disruption of existing fisheries. Caught in this Catch-22, the Commission has focused its attention on harvest allocations and data collection.