Sturgeon are native to rivers of the west coast of North America from central California to Alaska. The greatest number of sturgeon are in the Columbia River Basin. There are two types: green and white. Green sturgeon inhabit the salt water estuary and brackish backwaters up to about 40 miles inland from the ocean. They are known to be in the estuary in the summer and early fall, but spawning has not been documented. White sturgeon are far more numerous and historically inhabited the Columbia from the lower river to British Columbia, the Snake River to Shoshone Falls, and the Kootenai River from Kootenay Lake, British Columbia, to Kootenai Falls, Montana

Sturgeon below Bonneville Dam have access to the ocean; some populations are isolated between dams, and sturgeon in the Kootenai River are landlocked upstream of Bonnington Falls, which blocks anadromous fish passage into Kootenay Lake.

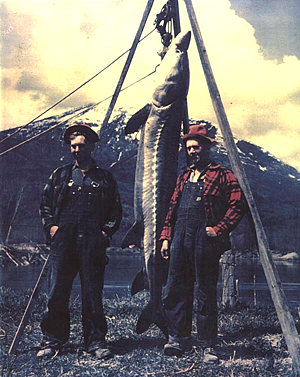

Sturgeon are the largest freshwater fish, capable of growing to more than 1,000 pounds and 10 feet in length. Commercial fishing for sturgeon began in the Columbia in the 1880s and peaked in 1892, when 5.5 million pounds (2.2 million kilograms) were harvested. Overfishing decimated the population by 1899; harvest remained low into the 1940s, but the population recovered and the commercial fishery expanded — with restrictions on the maximum size of fish that could be legally harvested. Total harvest increased steadily in the 1970s and 1980s.

Sturgeon grow slowly and live long lives — 80 to even 100 years. Female sturgeon do not reach spawning maturity until about age 15 or later, and they may spawn only every two to 11 years after that.

Hydropower dams have impacted sturgeon by altering the velocity and timing of river flows, which are important for spawning. Sturgeon also are susceptible to changes in water temperature, turbidity and depth, all of which are affected by dam operations. Of all the sturgeon populations in the Columbia Basin, those in the lower river are the most stable, possibly because they can utilize habitat in the river and the estuary, where there are abundant food fish for sturgeon.

In Idaho, a sturgeon rescue effort is under way for the most remote and isolated of the Columbia River Basin sturgeon, those in the Kootenai River. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service listed Kootenai River white sturgeon as an endangered species on September 6, 1994. Four years earlier, the Kootenai Tribe of Idaho initiated the Kootenai River White Sturgeon Study and Conservation Aquaculture Project to preserve the genetic variability of the population, begin rebuilding natural age class structure with hatchery-reared fish, and prevent extinction while measures are implemented to restore natural production of fish. Consistent with the project’s breeding plan and the Fish and Wildlife Service’s recovery plan, the tribe has been successfully incubating, hatching, raising and releasing sturgeon using the eggs and sperm of adult fish taken from the river — and later returned. Subsequent monitoring shows the juveniles are surviving.

In a shed on the Kootenai Tribe reservation, south of Bonner’s Ferry along the Kootenai River, a half-dozen blue tanks hold juvenile sturgeon that will be released into the river in an attempt to rebuild the population, which has been declining since the mid-1970s. The tanks are large---more than 10 feet across and four feet deep. In one, the fish range in size from about 12 inches to nearly three feet in length. Some of the juveniles are 12 years old. The fish swim lazily, circling the tank; some roll on their sides to eye curious visitors leaning over the edge.

“We are looking back in time,” Sue Ireland said. She manages the tribe’s sturgeon production and recovery effort. “From what we know of the archaeological record, this is what sturgeon looked like a million years ago — their eyes and nostrils, the pointy scutes on their backs and sides. These are survivors. If they could speak, they might say to us, ‘we’ve survived for a million years, including two extinctions; what have you humans done?’”

Ireland said the goal of the sturgeon aquaculture project is to protect the fish from extinction until suitable habitat conditions are re-established in the Kootenai River ecosystem so that sturgeon survival can improve beyond the egg/larval stage, and natural recruitment of juvenile fish into the population can be restored. The program is designed to produce four to 12 separate sturgeon families per year and up to 100 adults per family that survive to breeding age. The work is being coordinated with U.S. federal and state fish and wildlife agencies, and also with counterpart agencies in British Columbia, as Kootenai River sturgeon migrate back and forth across the border.

During the 11 years between 1992 and 2003, the conservation aquaculture program released more than 40,000 juvenile sturgeon of ages between 1 and 4 years. Subsequent studies showed that survival was about 60 percent for the first year in the river and 90 percent after that. The studies also showed that most of the fish in the river were bred in the hatchery. In 2003 the Idaho Department of Fish and Game sampled more than 600 sturgeon and determined that only 39 were of wild origin.

In light of the low number of wild juvenile sturgeon and the decline in the wild adult population, the tribe and its partners in the recovery effort decided to revise the breeding program. The new program, issued in 2004, called for spawning more fish and releasing more families, representing 3,000 - 4,500 fish per family annually — about double the previous amount — and releasing them at smaller sizes and younger ages. This is appropriate, Ireland said, because the next generation of fish will be almost entirely of hatchery origin. Producing more families and releasing larger numbers of fish per family should ensure that genetic diversity of the species is maintained and that sufficient numbers of fish survive the 20 or more years to spawning maturity, she said. The revised program also calls for releasing fish at more locations to take advantage of suitable habitat.

Related: 2018 Storymap on sturgeon