Kettle Falls (map) in present-day northeastern Washington was one of the most important Indian fishing sites on the Columbia River. Historical eyewitness accounts suggest the fishery at Kettle Falls might have been larger than the one at Celilo Falls several hundred miles downriver

Between 1,000 and 2,000 Indian fishers regularly used the site. Kettle Falls was located about 50 miles south of the Canadian border. The Kettle River flows into the Columbia from the west just above the falls, which today are under water. Lake Roosevelt, the reservoir behind Grand Coulee Dam, flooded the falls in 1940.

For centuries, Kettle Falls was the site of a vibrant fishery. Local Indian bands caught salmon and steelhead for their own use and also to trade for buffalo robes, horses and other goods brought by Indians who traveled to the falls from as far away as present-day Montana.

North West Company fur agent David Thompson was the first person to make a written description of Kettle Falls (various voyageurs and mixed-blood trappers probably preceded him, but left no record). In the spring of 1807 Thompson crossed the Rocky Mountains from present-day Alberta, charged with the twin tasks of establishing a viable trade circuit in the Interior and charting the Columbia River to the Pacific. From the source lakes of the Columbia in southeastern British Columbia, Kootenay (Ktunaxa) headmen directed him downstream on the Kootenay River, then south to the Clark Fork and Flathead drainages. Saleesh speakers there steered him farther south to the Spokane country, then back north through the Colville Valley to Kettle Falls.

It was June 1811 before Thompson arrived at this most important mid-Columbia fishery, crowded with people from all over the region waiting for the beginning of the year’s salmon runs. He and a trusted team of voyageurs retreated a few miles up the Colville River to build one of Thompson’s personally engineered cedar plank “batteaus” then, utilizing every bit of his four years of Columbia experience, made the 700-mile run from Kettle Falls to the ocean in only ten days. When Thompson returned to the falls two months later he built another large canoe and paddled north to the Columbia’s uppermost turn, thus completing the first formal survey of the river’s entire 1,243-mile length.

Viewing Kettle Falls in the summer of 1811, he named the place Ilthkoyape Falls and the Indians who fished there Ilthkoyape Indians. These are among the forebears of Indians who are today organized as the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation.

The origin of the word Ilthkoyape is unclear, but it probably came from “Ilth-kape,” the Salish word for “kettle,” and “hoy-ape,” the Salish word for “trap” or “net.” At the falls, Thompson observed Indians fishing with basket-like nets, catching the salmon as they fell back after trying to leap the falls. Thompson was the only one to use this designation. Other explorers who came later, among them Ross Cox, Alexander Ross and Gabriel Franchere, called the falls La Chaudiere (the caldron) because of the boiling appearance of the water as it plunged into pools below the falls.

Thompson found the local Indians friendly; they shared their food. But it wasn’t enough for Thompson’s hungry men, he wrote:

“On our arrival, the Chief presented us with a roasted Salmon and some Roots, but what was this small supply to nine hungry men, and as we found the Village had no provisions to spare we had to kill a Horse for provisions; this was a meat I never could relish, but my Canadians had strong stomachs, and a fat Horse appeared as much relished as a Deer.”

Thompson observed that the stomachs of salmon caught at the falls were empty. This he ascribed to their presence in freshwater, “which now has no food adapted to them [as they] ascend to the very place where they became alive.” And he recognized the importance of salmon in the diet of the Indians:

“The Salmon are about from 15 to 25 to 30 pounds weight here, well-tasted, but have lost all their fat, retaining still all their meat. Their flesh is red, and they are extremely well-made. . . .Whatever the history and the habits of the Salmon may be, they form the principal support of all the Natives of this River, from season to season.”

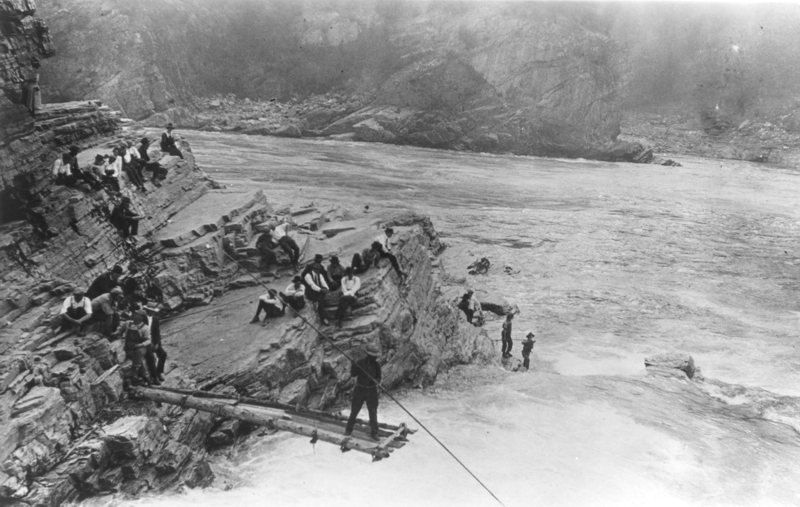

In 1841 Explorer Charles Wilkes observed Indians trapping salmon in baskets at the falls. He wrote that the Indians frequently caught as many as 900 salmon in 24 hours. That same year, 1841, Jesuit missionary Pierre-Jean De Smet established the St. Mary’s Mission in the Bitterroot Valley of present-day Montana, one of six missions he ultimately would found. In the summer of 1845 De Smet traveled to Fort Vancouver for supplies. His return journey took him past Kettle Falls. “The beautiful falls of the Columbia,” as he called them, were a two-day journey over the mountains from the St. Ignatius mission in the Flathead valley, and Indians from that area were among those who fished at Kettle Falls. De Smet estimated 800-900 Indians were gathered at the falls that August to fish for salmon. He spent nine days there. The respite afforded him the opportunity to carefully observe the salmon fishery. In a letter dated August 7, 1845, he wrote about his travels through the Oregon country, and described the Kettle Falls fishery:

“My presence among the Indians did not interrupt their fine and abundant fishery. An enormous basket was fastened to a projecting rock, and the finest fish of the Columbia, as if by fascination, cast themselves by dozens into the snare. Seven or eight times a day, these baskets were examined, and each time were found to contain about two hundred and fifty salmon. The Indians, meanwhile, were seen on every projecting rock, piercing the fish with the greatest dexterity.”

Colville Indians and others from the upper Columbia River continued to fish at the falls until the late 1930s, when Grand Coulee Dam finally exterminated the upper Columbia salmon runs and the falls were inundated by Lake Roosevelt. In June 1940, the Colville tribe feted the annual spring return of the salmon for the last time at an event they called the Ceremony of Tears . From time to time, when the level of Lake Roosevelt is extraordinarily low, the river swirls around the highest remnant rocks of the falls, creating a brief reminder of the tremendous cataract that once was there.