Indians of the Columbia River Basin were salmon fishers. Salmon spawned as far inland as the headwaters of the Columbia River, 1,200 miles from the ocean and were an important food to the people who lived along the river, and also to those who traveled far to trade for fish at established fisheries like those at Kettle Falls and Celilo Falls.

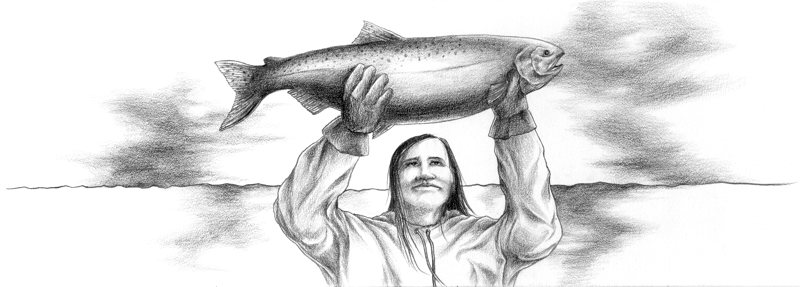

By about 1,500 years ago, Northwest Indians were arranged in tribes and identified themselves with specific areas or watersheds. Salmon was an important resource for many of the tribes, particularly those in the lower reaches of the Columbia River west of the Cascades, where salmon and steelhead were more plentiful than in rivers east of the mountains. The annual return of salmon and steelhead from the ocean had spiritual and cultural significance for tribes, and the fish had economic importance as a trade and food item. Tribes developed elaborate rituals to celebrate the return of the first fish. These first-salmon ceremonies were intended to ensure that abundant runs and good harvests would follow.

There is archaeological evidence of fishing at Kettle Falls on the Columbia in northeastern Washington as long as 9,000 years ago, but it is not clear that fish was being dried for winter consumption at that time.

At the time of the first contacts with Europeans, in the late 1700s and early 1800s, Columbia River Indians had well-established fisheries using nets and traps. Particularly in the lower river, from Celilo Falls to the ocean, the abundant salmon runs supplied a reliable and abundant source of protein in the Indians’ diet. Farther inland, where salmon were less numerous, other forms of animal protein, from deer, elk, and waterfowl, were as important or more so than salmon.

Indians were able to fish the salmon runs heavily and still enjoy multitudes of salmon year after year because they practiced a form of management in the form of rules and rituals that limited the catch at the same time it supplied their needs. Historian Joseph Taylor writes:

“In the Oregon Country, historical, ethnological and archaeological evidence suggests that aboriginal spiritual beliefs, ritual expressions, social sanctions and territorial claims effectively moderated salmon harvests. Myths, ceremonies and taboos restrained individual and social consumption, while settlement patterns and usufruct rights restricted access to salmon.”

According to Taylor, Indians developed a respect for salmon because it sustained their lives, and this respect shaped actions that moderated harvest and consumption. The salmon runs appeared at predictable times and places throughout the year, every year. Fishing, therefore, was a more efficient way to secure protein than through hunting land animals. “It is no wonder that salmon was a staple of aboriginal diets,” Taylor says.

West of the Cascades, where the Columbia and its tributaries ran thick with salmon in the spring, summer and fall, Indians lived in well-established and semi-permanent groups; east of the Cascades, Indians lived in smaller groups and migrated more frequently in search of food. Fishing sites on salmon-bearing rivers were traditional seasonal gathering places and permanent communities existed at important fishing locales such as Celilo Falls and Kettle Falls. Generally, Indians that lived east of the Columbia Plateau relied less on salmon than did Indians living to the west. But the plateau is not an absolute demarcation of the salmon culture. Some plateau tributaries of the Columbia, like the Spokane, and others to the east, like the Salmon and the Clearwater, supported large annual salmon runs that provided an important food source for tribes. Some of the largest salmon ever caught in the Columbia River Basin were fall Chinooks from the Spokane River, a plateau tributary. These were among the giants that non-Indian fishers in the lower Columbia River nicknamed “June hogs” because of the timing of their appearance in the river and their sheer size. Some weighed more than 100 pounds and were close to five feet long.

Interior Columbia Basin salmon fishing

There were a number of important fishing sites in the upper Columbia River Basin, and large numbers of Indian fishers. Eyewitness accounts described 1,000-2,000 fishers at Kettle Falls, 1,000-1,400 at Little Falls on the Spokane River, 1,000 at a site on the Little Spokane River, more than 1,000 at Spokane Falls and 250 on the Sanpoil River, a Columbia River tributary downstream from the Spokane. In fact, these accounts suggest that the highest concentrations of Indian fishers in the Columbia River Basin were at these interior sites, not in the lower Columbia area.

The Spokane Indians, for example, were salmon people. The tribe was arranged into three distinct bands along the lower, middle and upper reaches of the river according to the location of historic salmon fishing sites. While relations with their neighboring tribes, particularly the Coeur d’Alenes, at times were strained, salmon fishing and salmon trading brought the Spokanes into contact with many other tribes, sometimes from far away.

Historians Robert Ruby and John Brown write that when the Spokanes encountered a tribe whose language was not familiar, they would identify themselves with hand movements that suggested the side-to-side movement of a fish tail, as with a spawning salmon. They also put their hands to their mouths and patted their stomachs with satisfaction to demonstrate that fish fulfilled their hunger. In 1866, an Indian agent estimated that salmon make up five-eighths of the total diet of the Spokane Tribe.

The Spokanes were effective salmon fishers. The first big fishery on the Spokane was just below Little Falls, where the Indians built a rock wall part way across the river and a weir of willow poles just upstream, thus funneling the returning fish into an area where they could be trapped and speared when the weir was closed. In 1839, Christian missionary Rev. Elkanah Walker observed Indians fishing at Little Falls and wrote, “It is not uncommon for them to take 1,000 in a day. It is an interesting sight to see the salmon pass a rapid. The number was so great that there were constantly hundreds out of the water.”

In the spring, when the salmon began to return up the Spokane River, news of their arrival traveled quickly to other tribes in the area, including the Coeur d’Alene, Kalispel, Colville, Palouse, San Poil and Columbia tribes, and it was not unusual for 1,000 or more Indians to participate in the Spokane River fisheries. In addition to the fishery at Little Falls, there was a fishery at the mouth of the river, another near the mouth of the Little Spokane River and another at the base of the Spokane Falls in what is now downtown Spokane.

The Spokane Falls fishery was claimed by the Coeur d’Alene Tribe as well as the Spokanes. In 1826, botanist David Douglas watched Spokane Indians fishing near the Little Spokane River and wrote, “The natives constructed a barrier across the Little Spokane [where it enters the Spokane River]. . .After the traps were filled with salmon, the Indians would spear them. 1,700 salmon were taken this day, now 2 o’clock; how many more may still be in the snare, I do not know.”

At some of these fisheries, the catch regularly topped 800 salmon in a day, many weighing 40 pounds or more. The Spokanes traded dried salmon to Blackfeet Indians, who lived east of the Rocky Mountains in present-day Montana, for buffalo hides. In the modern era, salmon are gone from the Spokane River as the result of Grand Coulee Dam.

A sizeable harvest

The size of the total harvest by Indians in the Columbia River Basin is difficult to estimate. In 1940, researchers Joseph A. Craig and Robert L. Hacker estimated the catch at 18 million pounds per year, or more than half the size of the commercial harvest in 1933, which was 26 million pounds. The Indian harvest before the first contact with Europeans was a “very significant proportion” of the commercial catch of the modern era, the authors wrote. They based their estimate on an Indian population of 50,000 and consumption of one pound of salmon per day. Another researcher used a larger estimate of the Indian population (61,500) and, accounting for wastage (Craig and Hacker did not), estimated a Columbia River annual catch of 22, 274,500 pounds, which made the aboriginal fishery about the same size as the fishery of the 1940s. Estimates in the 1980s, using further revised population and consumption estimates, were even higher — more than 41 million pounds on average. Taylor points out that this would make the aboriginal fishery “fully comparable to the industrial fishery during its heyday between 1883 and 1919, which surpassed 41 million pounds only nine times.”

Decline of the fishery

While the biggest and most important Indian fishing sites were at Celilo and Kettle Falls, there were hundreds of smaller but nonetheless important fishing sites on the Columbia and its salmon and steelhead-bearing tributaries. As non-Indian settlers steadily moved into the Columbia River Basin beginning in the 1840s, Indians increasingly were crowded off their traditional fishing and village sites. In 1850 near The Dalles, artist George Catlin observed:

“The fresh fish for current food and the dried fish for their winter consumption, which had been from time immemorial a good and certain living for the surrounding tribes, like everything else of value belonging to the poor Indian, has attracted the cupidity of the ‘better class,’ and is now being ‘turned into money,’ whilst the ancient and real owners of it may be said to be starving to death; dying in sight of what they have lost, and in a country where there is actually nothing else to eat.”

Through the Treaties of 1855, negotiated during a time of escalating tension between Euro-Americans and Columbia River tribes, the federal government attempted to secure title to Indian land and create reservations for tribes. The tribes sought to reserve for themselves access to their usual and accustomed fishing places, and the United States agreed. But the tide of immigration and lax enforcement of fishing rights overwhelmed traditional practices. Author Click Relander wrote, “The days [were] long past when the River People [specifically, the Wanapum Tribe near Priest Rapids] were able to spear or net most of their food from the river. The old men say that the last runs of the big red-fleshed salmon ended around 1905. That was when the fish wheels were dragging salmon out of the water by the hundreds of thousands and the commercial slaughter was at its height.”

In 1942, Edward J. Swindell, an attorney who was investigating Columbia River fishing sites as part of the proceedings in a lawsuit, observed the fishing activity in the vicinity of Celilo Falls and later wrote that if a dam were built at The Dalles, as was under consideration at the time,

“. . .the few remaining places in the mid-Columbia River area which constitute the bulk of the commercial Indian fishery on that river will be inundated by the backwater from such dam. Since they are practically the only places in that area where the Indian’s catch can be disposed of commercially, they are of inestimable value to the Indians. The loss of such places would be as calamitous to them as was the loss they sustained as a result of the flooding of a considerable number of commercial and subsistence fishing grounds on account of the construction of the Bonneville and Grand Coulee dams.”

In fact, that is precisely what would happen. On April 27, 1945, the Colonel in charge of the Portland district of the U.S. Army Engineers met with local Indians at The Dalles to listen to their concerns about the government’s proposal to build The Dalles Dam, which indeed would flood the historic fishing grounds at Celilo Falls about five miles upstream of the dam site.

Francis Seufert, a fish buyer for his family’s local salmon fishing and canning business, was invited to attend the meeting by a friend, an attorney representing the Indians. In Wheels of Fortune, Seufert’s book of recollections about the Seufert family business and salmon fishing, he recalls the meeting, which took place in a room in The Dalles City Hall:

“The Indian chiefs were all old men, very dignified. Each of the old chiefs came forward, one at a time, shook the colonel’s hand and talked through an interpreter giving the Indians’ story of their dependence on Columbia River salmon, and the serious effect that the building of the dam at The Dalles would have on the Indians’ livelihood. The old chiefs made many references to the Indian Treaty of 1855, the terms of the treaty and the obligations of the U.S. government to uphold the sacredness of the treaty and not build The Dalles Dam.

“The elegance and dignity of the old Indian chiefs in stating the Indians’ case, their choice of words, the beautifully put phrases, excellent prose, their poetic way of using picturesque and yet descriptive speech, was something that no one present would ever forget. The simplicity of the old chiefs’ speech was a moving thing to hear. I was impressed with the respect that the old chiefs were held in by the younger Indians. I had never seen anything like it before. After all the old chiefs had spoken, a number of the old women also addressed the colonel, these old Indian women telling the Indians’ side of the story of previous promises, and only receiving broken promises and excuses from the U.S. government. These old women pleaded with the colonel not to let that history from the Indian standpoint repeat itself again.

“After the old chiefs and the old Indian women had all had their say, the good colonel expressed extreme sympathy for the Indians, and wanted them to know that the Army Engineers would have nothing to do with the decision to build a dam at The Dalles, only Congress could do that.

“As I left the meeting and walked down the stairs, I couldn’t help feeling I had witnessed another bit of history in our government’s dealing with the American Indian, and I was sure of one thing at the time: if local merchants saw a chance to make money through the building of a dam at The Dalles, then nothing as simple as an Indian treaty signed some 90 years before was going to stand in the way.”

Seufert believed the government treated Indians and non-Indians equally in providing compensation for the impacts of The Dalles Dam. Compensating Indians for the loss of fishing opportunities at Celilo Falls was no different than compensating his business for the loss of fishing sites when the reservoir rose behind The Dalles Dam, he wrote. To Seufert and other non-Indian fish processors, salmon were a commodity; the historic cultural significance of the Celilo fishery to Indians was important, but not an overriding concern. Fishing was a business, whether the fishers were Indians or not.

As a consequence of the construction of The Dalles Dam and the impending blockage of the river, 1956 was the last year for the treaty Indian fishery at Celilo Falls. Until that year, commercial fishing above Bonneville Dam was open to both Indians and non-Indians. Using dip nets, the Indian fishers caught 910,000 pounds of salmon and steelhead in 1956, the second-lowest catch since 1938 (also in 1956, non-Indian commercial fishers caught 1,023,000 pounds of salmon and steelhead above Bonneville Dam). The lowest Celilo catch of the 1938-1956 period was 796,000 pounds in 1954. In 1955, the Celilo fishers took 1,983,100 pounds. The greatest Celilo catch between 1938 and 1956 was in 1941: 3,464,900 pounds.

Litigation

In 1957, Washington and Oregon closed the fishery above Bonneville Dam, the fishing area designated by the states as Zone 6, to all commercial fishing. Indian-only fisheries occurred in Zone 6 between 1957 and 1968, but these were for ceremonial and subsistence purposes, not commercial purposes, and were regulated by the treaty tribes, not by the states. Meanwhile, tribes battled in court to restore their commercial fisheries in Zone 6. In 1968, responding to a lawsuit, Oregon and Washington re-established the Indian-only commercial fishery in the Columbia mainstem above Bonneville Dam. In 1969, responding to another lawsuit, the states defined the area of the fishery, extending the eastern limit from the mouth of the Deschutes River, which was the limit prior to 1957, to McNary Dam. It is 140 miles between the two dams. The Zone 6 fishery is conducted primarily with set nets — nets that are anchored in the river — and with dip nets from fishing platforms along the shore.

In the 1960s, Oregon decided to regulate Indian fishing and non-Indian fishing in the same way, believing that language in the 1855 treaties guaranteeing Indians the right to fish “in common with” non-Indian citizens meant all had equal rights to the fishery, and that all could be regulated equally. A group of Indians led by Richard Sohappy, a Yakama member, sued the state. The United States government joined the Indians as plaintiffs, and the case was named U.S. v. Oregon.

The case was argued before U.S. District Judge Robert Belloni of Portland. In his decision, handed down on July 8, 1969, Belloni ruled that the Indians have “an absolute right” to the fishery and are entitled to “a fair share of the fish produced by the Columbia River system.” Accordingly, Belloni ruled, Oregon:

“. . .must so regulate the taking of fish that, except for unforeseen circumstances beyond its control, the treaty tribes and their members will be accorded an opportunity to take, at their usual and accustomed fishing places, by reasonable means feasible to them, a fair and equitable share of all the fish which it permits to be taken from any given runs.”

Belloni wrote that most of the argument in the lawsuit centered around Oregon’s interpretation of that “fair and equitable” provision. Attorneys for the state argued that the provision only gave the Yakamas and other treaty Indians the same rights as all other citizens. The judge dismissed that argument, commenting: “There is no evidence in this case that the defendants have given any consideration to the treaty rights of Indians as an interest to be recognized or a fishery to be promoted in the state’s regulatory and developmental program.” He called the state’s actions “discriminatory,” and added: “Such a reading would not seem unreasonable if all history, anthropology, biology, prior case law and the intent of the parties to the treaty were to be ignored.” Belloni held the state’s argument that the treaties only gave the Indians an equal right to fish with other residents of the state simply was not fair compensation for the lands they had ceded to the United States in the treaties, which amounted to more than 64 million acres. There were far more non-Indian fishers than Indian fishers, and the judge declared that the effect of the state’s approach was to “crowd the Indians out” of their historic fishing sites. This was a violation of the treaties, Belloni said. It was not the intent of the parties to the treaties that the Columbia River Indians should “occasionally dip their nets,” he wrote, but that they fish, according to the language of the treaties, “in common with” non-Indians.

In 1974, U.S. District Judge George Boldt of Tacoma refined Belloni’s “fair and equitable share” rule in United States v. Washington to mean 50 percent, and in 1975 Judge Belloni applied the 50-percent rule to the Indian fishery on the Columbia. In 1979, the 50-percent issue reached the United States Supreme Court in Washington v. Washington State Commercial Passenger Fishing Vessel Association. The Supreme Court rejected Washington’s argument that Indians and non-Indians had an “equal opportunity” to the fishery, stating: “In our view, the purpose and language of the treaties are unambiguous; they secure the Indians' right to take a share of each run of fish that passes through tribal fishing areas.”

Harvest management complexities

As tribes sought to defend and clarify their fishing rights in court, fisheries management became increasingly complex. The Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife described the problem in a 1976 press release:

“Legal decisions have substantially increased the complexity of the management problems facing state agencies. In the course of clarifying basic legal issues, the courts have been interjected into the entire scope of fisheries management. The final results have rarely been satisfactory to either side. . . .[The role of Indian tribes] has been to secure and preserve fishing rights provided by the treaties with the United States. The role of the states . . .has been to balance biological, legal, cultural, political and economic realities of uneven proportions.”

In February 1977, the four Columbia River treaty tribes — Yakama, Warm Springs, Umatilla and Nez Perce — and the states of Washington and Oregon completed negotiations on “A Plan for Managing Fisheries on Stocks Originating from the Columbia River and its Tributaries Above Bonneville Dam.” For five years, the 1977 Plan, as it was called, was the basis for salmon harvest management decisions in the tribal-only fishing zone between Bonneville and McNary dams. The agreement expired in 1982. Nonetheless, Indian commercial fishing in Zone 6 continues to be regulated jointly by the states of Oregon and Washington under the 1977 Plan and the continuing supervision of the federal court in U.S. v. Oregon. On this same stretch of river, ceremonial and subsistence fisheries also are regulated under U.S. v. Oregon. It is up to the tribes to allocate between commercial and ceremonial/subsistence fisheries within the confines of U.S. v. Oregon.

In Phase II of United States v. Washington, decided in 1980, U.S. District Judge William Orrick of Tacoma ruled that the treaty promise is meaningless if there are no fish to harvest and that the tribes were entitled to more than the “right to dip one’s net into the water . . .and bring it out empty.” Orrick ruled that the treaty right extended to environmental conservation, as the tribes have a right “not to have the fishery habitat degraded by the actions of man which cause environmental damage resulting in such a reduction of available harvestable fish that the moderate living standard, as implemented through the allocation orders of the District Court in Phase I, cannot be met.”

In 1988, the U.S. District Court in Portland approved the Columbia River Fish Management Plan negotiated by Oregon, Washington, the United States and the four mid-Columbia River treaty tribes. In essence a renegotiation of the plan that expired in 1982, the goal of the new plan was to restore runs and allocate harvest of fish in the Columbia River. All management of Columbia River fish runs and fisheries by the states of Oregon and Washington is based on the plan. Idaho and the Shoshone-Bannock Tribe dissent from certain features of the plan.

Harvest in an era of scarcity

As management plans and their complexity increased, the number of fish available for harvest continued to decline. In December 1992, Bob Tomanawash, a Wanapum Indian living at Priest Rapids, Washington, on the Columbia, told the Tri-City Herald newspaper of Kennewick, “Now, you catch fish just a little here and little there.” It was a sentiment that would be expressed over and over as Indian fishers, like their non-Indian counterparts, confronted the problem of declining runs in the middle and late 1990s.

Over time, many creative responses were attempted to allow harvest while also permitting enough fish to escape capture to spawn and preserve the runs. In the lower Columbia, a terminal fishery was developed for non-Indian commercial fishers. Salmon are raised in floating net pens in bays and sloughs and released the appropriate age to go to the ocean. The fish instinctively return to the same bays and sloughs to spawn, and are harvested by commercial fishers using their traditional gillnets. This reduces the harvest pressure on the upriver stocks, some of which are threatened and endangered species, and allows for a greater harvest in Zone 6.

Meanwhile in Zone 6, there were experiments to fish more selectively. In September 2000, Indian fishers tried a new kind of net in Zone 6. This one had larger-mesh (eight or nine inches) than the nets the fishers used previously (six or seven inches). The intent was that Endangered Species Act-listed wild B-run steelhead from the Snake River would escape capture and return to Idaho to spawn. The fish are smaller than fall Chinook salmon, which are fished at the same time. The alternative was to shut down all fishing in Zone 6 until the steelhead had passed. On the opening day of the season, the agency counted 626 nets in the river. Of these, only 191 were of the new variety (the nets could be identified by their color-coded floats). The nets were purchased for the fishers by the Bonneville Power Administration, as part of its legal requirement to mitigate the impacts of hydropower dams on fish and wildlife of the Columbia River Basin. Researchers who monitored the deployment of the nets for Bonneville were not discouraged by the initial deployment, even though it was lower than anticipated. In a report, issued a year later, in September 2001, they commented that “fishers did not have time to complete assembly of all nets, but remaining nets are expected to be phased into future fisheries.” In all, the experiment was considered a success. The larger-mesh nets allowed Indians to fish longer for fall Chinook because fewer of the wild, and less numerous, steelhead were caught.

Another experiment that also proved successful was the deployment of nets with a very small mesh that entangle fish by their teeth. Unlike traditional gillnets, in which fish suffocate, so-called tangle nets ensnare but do not kill the fish, allowing the fisher to release fish that are not designated for harvest.

Fishing is more than a livelihood for Columbia River Indians. It is culture. Not only is harvest important for Indians, but restoring salmon and steelhead runs is, too. The tribes manage important habitat restoration programs and hatcheries. These are having successes. Salmon are returning back up the Umatilla River of Oregon after being eliminated for more than 60 years because irrigation withdrawals drained the lower reaches of the river dry every spring and summer. But thanks to an innovative water exchange program negotiated by the tribe, irrigators, and state and federal officials, water is flowing in the river again, and the tribe operates a state-of-the-art hatchery with the goal of rebuilding naturally spawning runs and improving fishing opportunities on the reservation over time. The same thing is happening in the Yakima River Basin, where the Yakama Nation operates a hatchery that is producing fish to repopulate streams throughout the Yakima Basin, which once was one of the largest contributors of salmon and steelhead to the Columbia River runs. Another large tribal facility is being planned and constructed by the Nez Perce in the Clearwater and Salmon river basins of Idaho, tributaries of the once-prolific Snake River.

It is hoped that over time, these facilities and activities will rebuild salmon and steelhead runs and increase harvest opportunities for both Indians and non-Indians. The importance of the salmon culture to Columbia River Indians, the culture that is the driving force behind the long history of litigation over fishing rights, the tribes’ fisheries management, and the efforts to both conserve and produce fish, cannot be understated. In 1992, Louie Dick, Jr., a member of the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Reservation, commented on the cultural legacy of fishing:

“Don’t call us a minority. We come from the land. We are the earth, we are the land. The others occupy the land. When you destroy the salmon, you destroy me. The salmon made a commitment to return and to give life. He’s following his law by coming. We are violating our own law by not doing everything we can to get him back.”