Sea lions are feasting on Columbia River spring Chinook salmon and may be killing as much as 40 percent of the annual run

Over the last decade or so, more and more of the marine mammals have crowded into the Columbia River estuary, where in 2018 they numbered an estimated 4,000 animals, most of them California sea lions. The others are Steller sea lions. That’s up from a few hundred, at most, 10-15 years ago.

Sea lions are so prolific in the lower Columbia in the spring that they take over boat docks to rest; in response the Port of Astoria has closed the East Mooring Basin docks, where curious onlookers line the rails of a pier with their cameras and cell phones to snap photos amid the cacophonous barking and snarling as the huge animals, some weighing well over 700 pounds, lie shoulder to shoulder and sometimes climb over each other to gain a small piece of open dock. Often two can be seen bumping each other chest to chest, heads up, teeth bared, each trying push the other into the water.

Sea lions, awkward on land as they propel themselves in a jerky, ambling, rumbly-blubbery three-point ramble balanced between their two flippers and tail, are sleek, swift, and graceful in the water.

And hungry.

The California sea lions that annually swell the Columbia River estuary population in the spring are males that migrate up the West Coast to feast on fish, including salmon, steelhead, sturgeon, and lamprey, before returning to several islands off the coast of Southern California in June to mate. Steller sea lions come to the Columbia River from breeding grounds in Alaska.

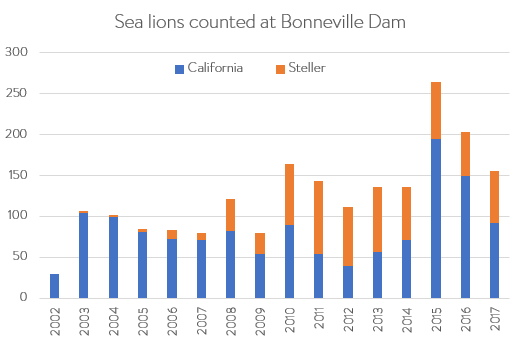

Sea lions, Californias and Stellers, have been roaming the West Coast for probably hundreds of years, possibly venturing into the Columbia River from time to time. But they only began entering the Columbia en masse to hunt and feed in the 1980s, according to a fact sheet by the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife. They began showing up at Bonneville Dam, 146 miles inland from the ocean, in 2003, an area they had not frequented before.

Of the two, Californias are more numerous and Stellers are larger. California sea lions can grow to about seven feet in length and weigh up to 850 pounds. Stellers can grow to 11 feet and weigh 2,500 pounds. Both species are managed under the federal Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972. Stellers were divided into two populations, one west of 144 degrees west longitude (approximately as far west as Anchorage, Alaska), and one east of that line. In 1997, the western population, primarily in Alaska, was listed as endangered and the eastern population was listed as threatened. In 2013, the eastern population, the one that frequents the Columbia River, was removed from the list and their threatened status canceled because the population had rebounded.

In a January 2018 news release, NOAA Fisheries, which has management authority over sea lions, wrote that the West Coast population of California sea lions has “fully rebounded” under the protection of the 1972 Marine Mammal Protection Act. Today, the population is healthy and robust, NOAA researchers said, citing the results of a study that found the species increased from fewer than 90,000 animals in 1975 to an estimated 281,450 in 2008, which was roughly the carrying capacity for sea lions in the California Current Ecosystem at that time. The population then fluctuated around that level, reaching a high of 306,220 in 2012 before declining below the carrying capacity in the years since as ocean conditions changed and prey became less abundant. As the overall population declined, the number of animals in the Columbia River estuary steadily increased.

Threat to listed species, threat to regional investments

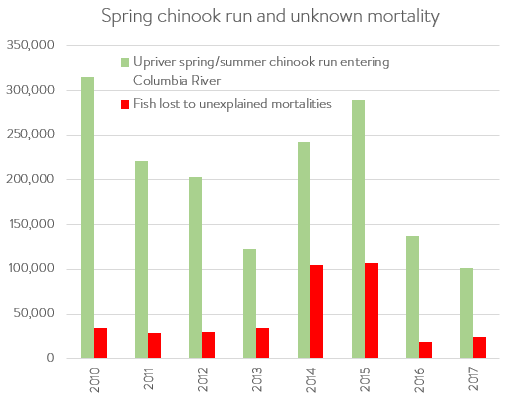

The population rebound is very good news for the species, but the way in which the population has expanded its presence in the Columbia River is not good news for Columbia River spring Chinook, an endangered species. NOAA Fisheries research conducted since 2010 between Astoria and Bonneville Dam has identified an “unexplained mortality” of the fish that varies from year to year but has not been lower than 11 percent of the run (in 2010), which translated to 34,688 fish in that year. In 2017, the unexplained mortality was estimated at 24 percent, which given the below-average run size, translated to 24,242 fish. The highest mortality as a percentage of the run was in 2014, when an estimated 104,333 fish, or 43 percent of the Upper Columbia spring Chinook run entering the river that year (242,635 fish), were lost between Astoria and the dam to the unexplained mortality, which the chief researcher, Dr. Michelle Wargo-Rub, said can be attributed to sea lions.

In contrast, Columbia River fisheries – sport, commercial, and tribal – are much more constrained in terms of protecting weak species. Commercial and recreational fisheries in the lower Columbia River, the same area where sea lions prey on salmon and steelhead, target hatchery fish and are restricted to an incidental take of no more than 2 percent of the annual wild-fish return.

Video: U.S. Army Corp of Engineers

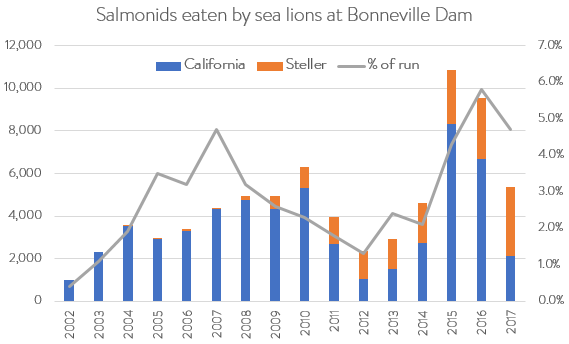

Every year since 2002, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers has observed sea lions killing salmon, sturgeon, and lamprey in the area immediately downstream of Bonneville Dam between the first of January and the end of March, the time period when the largest number of sea lions are present and adult spring Chinook are migrating upriver. In 2017, the Corps estimated that sea lions consumed between 4,759 and 5,227 salmonids (salmon and steelhead) at that location. During that period, NOAA researcher Dr. Wargo-Rub estimated that 24,242 salmonids were consumed by sea lions, about 6,000 of them within four miles of the dam, which is farther downriver than the Corps observers are able to see from their positions around the dam. So the numbers are similar.

Salmon and steelhead recovery in the Columbia River Basin costs around $300 million a year, and nearly all of that is paid by electricity ratepayers of the Bonneville Power Administration, which has a legal obligation to protect and enhance fish and wildlife affected by hydropower dams in the basin. Bonneville Dam blocks the river, and while adult fish are able to pass using fish ladders, the presence of the dam and the limited number of fish ladders provide an ideal location for sea lions to prey on fish. NOAA Fisheries, Bonneville, the Council, and others are concerned that the increasing sea lion predation on ESA-listed species is offsetting the large investments in salmon recovery associated with habitat, dam operations, harvest, and hatcheries.

The Columbia River spring salmon run includes 32 distinct populations of Chinook that are listed as threatened or endangered under the federal Endangered Species Act, as well as many non-listed populations. Of particular concern are upper Columbia spring Chinook, listed as endangered, and Snake River spring/summer Chinook, listed as threatened.

“Our panel of independent scientists is alarmed by the steady decline in survival of ESA-listed, upper Columbia spring Chinook salmon in the Columbia River estuary, where research indicates predation by sea lions on these fish is intense,” said Guy Norman, a Washington member of the Council and chair of the Council’s Fish and Wildlife Committee. Before being appointed to the Council in 2016, Norman directed the Southwest Washington division of the state Department of Fish and Wildlife.

The danger to these runs, particularly upper Columbia spring Chinook, was highlighted in a February 2018 report by the Independent Scientific Review Board, a panel of scientists that advises the Council, NOAA Fisheries, and Columbia River Indian tribes. In their report, the ISAB cited predation by sea lions in the lower Columbia River as one of the threats that may be contributing to the continuing low numbers of Chinook.

“The continuing temporal increase in pinniped [sea lion] numbers [in the lower Columbia] may be an important factor limiting Upper Columbia spring Chinook abundance,” The ISAB reported. The ISAB report continued: “Surprising new evidence indicated a steady decline in estuarine survival of the combined runs of adult middle and Upper Columbia River spring Chinook and Snake River spring/summer Chinook (from 90 percent in 2010 to 69 percent in 2013). Survival was consistently higher for Chinook arriving late in the run compared to those returning early or at the peak, when predation by pinnipeds would have been more intense. The declining survival rates also coincided with the growing presence of sea lions and seals in the estuary.”

Not everyone agrees predatory sea lions need to be removed. The Humane Society of the United States, which has litigated to prevent the lethal removal of the most aggressive sea lions in the Columbia, say sea lions are unfairly targeted because they contribute only a small percentage of the total take of Chinook salmon. In an April 2016 blog post headlined "Eating Salmon Is A Crime – But Only If You’re a Sea Lion," the Society stated, “We humans are responsible for a far larger share of the mortality” through impacts such as sport and commercial fishing, hydropower dam operations, predation by introduced non-native species like Bass and Walleye, and failed culverts that block fish passage to spawning and rearing habitat.

Data for tables: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, NOAA Fisheries

There is no question the population of upper Columbia Spring Chinook has been historically impacted by a number of factors including dam passage, habitat degradation, bird predation, and fishing, but the impacts from those factors have been reduced to aid recovery while sea lion predation on adult salmon is increasing at alarming levels. According to the 2018 Joint Staff Report: Stock Status and Fisheries for Spring Chinook, Summer Chinook, sockeye, steelhead, and other species issued by the Oregon and Washington departments of fish and wildlife in February, the 2017 upriver (destined to spawn upriver from Bonneville Dam) spring Chinook return to the mouth of the Columbia River, which includes fish destined for Snake River tributaries, totaled 115,821 adult fish. Of these, 11,156 were designated upper Columbia River fish, and of these, 2,514 were considered "natural origin" (wild) fish.

According to the recovery plan for ESA-listed upper Columbia spring Chinook, developed by the Upper Columbia Salmon Recovery Board in coordination with NOAA Fisheries, the species will be considered recovered when annual returns are at least 4,500 successfully spawning natural-origin adult fish across the three primary populations — 2,000 in the Wenatchee, 500 in the Entiat, and 2,000 in the Methow. These numbers are considered reasonable considering the estimated smolt production capacities and smolt/spawner ratios, historical production levels, and general conservation guidelines of the rivers.

Current numbers provided by NOAA and reported on the Council’s website, are far lower. In 2017 the number of natural origin spawners was estimated at 154 (excluding jacks) in the Methow; 121 (excluding Jacks) in the Wenatchee, and no adults but 63 jacks in the Entiat.

Legislation aims at better control of aggressive predators

The plight of these fish has drawn the concern of the region’s political leaders. The governors of Washington, Oregon, and Idaho wrote a letter to the Northwest members of the House of Representatives in January 2018 urging them to support bipartisan legislation introduced by Rep. Jaime Herrera-Beutler (R-WA) and Rep. Kurt Schrader (D-OR), H.R. 2083, the Endangered Salmon and Fisheries Protection Act. The legislation would allow NOAA Fisheries to issue one-year permits to Washington, Oregon, Idaho, the Nez Perce Tribe, the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation, the Confederated Tribes of the Warm Springs Reservation of Oregon, the Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation, the Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission, and the Cowlitz Indian Tribe to kill the most aggressive, problematic sea lions in the Columbia River near Bonneville Dam and in certain tributaries in order to protect fish from sea lion predation. Washington Council member Guy Norman acknowledged the team effort, noting that the Corps of Engineers “has been a true partner,” and that observations of predatory sea lions by the Corps at Bonneville Dam "are key to helping the states identify animals for branding and removal."

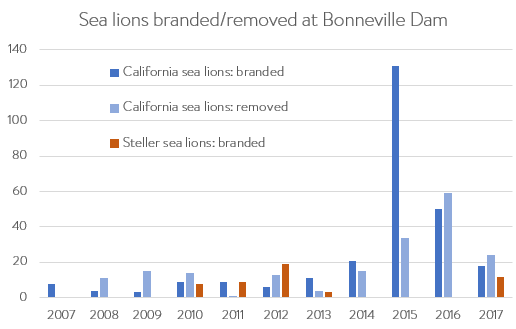

The targeted animals must be individually identifiable (problem animals are first captured, branded, and released), not listed for protection – thus, the proposed law does not affect Steller sea lions – and must have been observed repeatedly preying on fish.

“As Governors who are working to recover Columbia Basin salmon and steelhead, we urge you to support legislation aimed at reducing sea lion predation on threatened and endangered and other at-risk fish populations,” the governors wrote in their letter. “Although several hundred million dollars are invested annually to rebuild these native fish runs, their health and sustainability is threatened unless Congress acts to enhance protection from increasing sea lion predation.”

The bill passed the House in the fall of 2018. After that, a bipartisan companion bill in the Senate, S.3119, introduced by Sen. James Risch (R-ID) and Sen. Maria Cantwell (D-WA) was approved. President Donald Trump signed the bill into law on Dec. 18, 2018. The Council has long supported legislation to improve the control of the most predatory sea lions in order to improve adult salmon survival. In a May 2018 letter to Sen. Risch, the Council commented: “All other sources of mortality are being reduced while predation by sea lions increases. It is time to update the Marine Mammal Protection Act to speed the process of removing the most problematic sea lions.”

In the recovery plan for upper Columbia spring Chinook, the Upper Columbia Salmon Recovery Board supports the “…immediate adoption of more effective predator control programs, including lethal removal when necessary, of the marine and avian predators that have the most significant negative impacts on returns of Upper Columbia Basin ESA-listed salmonid fish stocks.”

The Marine Mammal Protection Act was amended in 1994 to provide a means for states to kill California sea lions that threaten recovery of ESA-listed salmon and steelhead. In March 2008 fish and wildlife agencies in Washington, Oregon, and Idaho received permission under Section 120 of the Act to remove as many as 92 individually identifiable sea lions annually that have been observed preying on salmon and steelhead below Bonneville Dam. Lethal removal is allowed if specific criteria are met – the animals must be individually identifiable and must have been observed repeatedly killing fish – but the states prefer to send the animals to zoos or aquariums.

Meanwhile, Oregon’s two senators, Ron Wyden and Jeff Merkley, introduced their own sea lion bill, which differs from the Risch and Cantwell bill in at least two important ways. First, the Oregon bill would allow tribes with “historic interests” in the river, as opposed to treaties, to help manage sea lions. This provision concerns other tribes and states because it could be seen as conferring management authorities to tribes that do not currently have them. Second, the bill would prohibit the use of firearms to lethally remove the most problematic sea lions.

Trouble at Willamette Falls

Sea lions are showing up at the base of Willamette Falls on the Willamette River a dozen miles south of Portland in increasing numbers, feeding on spring Chinook, steelhead, and lamprey. According to a 2017 report by the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife (ODFW), the predation is pushing wild winter steelhead to the brink of extinction — up to a 90-percent probability that at least one population of the species will go extinct in the near future unless predation by sea lions is reduced.

“The near-term risk of wild steelhead extinction can be significantly reduced or avoided by limiting sea lion access to Willamette Falls,” according to the ODFW report.

Predation adds to other problems the Willamette steelhead face, including harvest, interactions with hatchery fish, and lost or degraded habitat. ODFW biologists believe sea lions consumed one-quarter of the 2017 wild winter steelhead run, which sunk to an all-time low of just 512 fish crossing the falls.

In February 2018, ODFW captured two California sea lions at the base of the falls. One had been there regularly since 2009, eating salmon and steelhead. Relocated 200 miles away to a beach south of Newport, Oregon, he was back at the falls in three days. The other, relocated a day after the first one, was back in six days. The agency has permission to kill predatory sea lions at Bonneville Dam and sought the same authority for Willamette Falls. ODFW applied to NOAA Fisheries for that permission in October 2017, and NOAA granted permission in November 2018. See also the ODFW news release.

In its application, the department acknowledged that other factors contributed to the decline of Willamette salmon and steelhead, such as dams that block access to historic habitat, for example, but noted: “In areas where salmonid abundance is low, even a modest increase in predation by pinnipeds can result in serious negative impacts to the survival and recovery of individual salmonid populations.”

A cautionary tale

The Council, in its letter supporting the Risch/Cantwell bill, reminded the senators of what happened to wild Lake Washington steelhead when predation by sea lions at the Ballard Locks in Seattle was not effectively controlled. The locks connect the freshwater lake to the salt water of Puget Sound. It was the mid-1980s, and sea lions discovered the Sound-side entrance to the locks was a great place to prey on adult salmon and steelhead migrating from the ocean to the lake to spawn.

The dire warnings of fishery scientists were not heeded, the most aggressive predator sea lions were not removed, and so many winter steelhead were killed that the run became functionally extinct. At the time, the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife used various methods of non-lethal hazing, to no effect. Similarly today, in response to the spring onslaught at Bonneville Dam, the Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission and the U.S. Department of Agriculture harass sea lions from small boats and from shore to try to keep them away from salmon, but the effect is only temporary.

In October 2018, the Corps of Engineers published a draft report on sea lion predation on fall Chinook in the Columbia River, the first time recently the Corps has reported on fall predation. Final reports on spring, summer, and fall predation in 2018 are due in January 2019. The fall report responds to concerns, notably from NOAA Fisheries, that sea lion numbers are rising at the dam, along with the numbers of fish they are killing, and the fact that some sea lions appear to be more or less permanent residents at Bonneville Dam, particularly Stellers.

The last Steller of the summer left the area of the dam on June 24, but as the fall Chinook began to return in July and August, the Stellers returned, too. By October, the daily average number of Stellers was between 16 and 17; there were no California sea lions. The number of Stellers arriving with the fall Chinook run was higher than the 10-year average, and their numbers increased more rapidly than usual, the Corps reported.

Meanwhile, the fall Chinook run was smaller than usual. Stellers were observed taking Chinook, coho, steelhead, and sturgeon. Harassment, which includes firing at them with rubber buckshot, chasing them in small powerboats, and lobbing underwater firecrackers at them, has little effect, and under the law Stellers cannot be lethally removed.

The Corps concludes its draft 2018 report, as it did in its 2017 final report on predation at Bonneville, with a reminder of the near-eradication of Lake Washington steelhead by sea lions, and a warning:

“As the winter Steelhead passing Ballard Locks are now functionally extinct, in part, due to pinniped predation, the Upper Willamette River winter Steelhead are reportedly facing the same challenges to some extent due to pinniped predation. Data collected this year suggest the winter Steelhead near Bonneville Dam are also at risk. Fish and wildlife managers need to take action to ensure the continued existence of Steelhead, and other threatened and endangered anadromous fish species.”

According to the draft report, more than 5 percent of the winter steelhead run at Bonneville was consumed by Steller sea lions in 2018. That’s higher than in the past, and kelts – steelhead that spawn, go back to the ocean and return to spawn a second time – may be part of the take. According to the draft report, “It is plausible that the large number of adults consumed in each powerhouse tailrace includes some kelts.”

This, combined with the increasing numbers of Steller sea lions at Bonneville Dam, is cause for concern. According to the draft report:

"The tides of pinniped predation on threatened and endangered fish have changed at Bonneville, wherein the primary predator of these fish is now the Steller sea lion, a species for which the fish and wildlife managers have no plan to control or manage. Preliminary data from the fall and winter period and the current data from the spring sampling period found striking evidence for a biologically significant impact to ESA-listed B-run and winter Steelhead. The potential impact to ESA listed Chum salmon downstream of Bonneville further highlights the issue of the prolonged residency and increased abundance of quasi-resident Steller sea lions foraging near Bonneville, and provide reason for concern.”

The draft 2018 report recommends, as did the final 2017 report, a review of the current California Sea Lion management plan and the development of an “equitable Steller Sea Lion management plan,” and stresses the importance of adaptive management of the predation problem: “For it is now through adaptive management that an ecological balance of interspecific competition can be found to ensure the continued survival of ESA-listed Pacific salmon.”

In the final report on 2017 predation at Bonneville, and again in the draft 2018 report, the Corps confirmed that non-lethal hazing is largely ineffective, typically driving sea lions away from the tailrace area for only a short time, if at all. Steller sea lions seem to be particularly habituated despite repeated hazings.

In both reports, the Corps advises, “the short-term effects of hazing call to question the relative value of such techniques and beg for better, more effective alternatives.” Both reports conclude with encouragement to fishery managers to pursue an adaptive management approach to dealing with predation by sea lions.

In language only a scientist could love, the reports read: "Without such management, anthropogenic and pinniped predatory pressures may synergistically function to extirpate runs of a vital prey resource.”

Translation: The human species and the pinniped species are competing for the same limited resource, the salmonid species. Without effective management, the combination of human-caused impacts and predation by sea lions will doom some fish runs.

Links:

- Endangered Species Act Section 7(a)(2) Consultation, Supplemental Biological Opinion, Supplemental Consultation on Reducing the Impacts on At-risk Salmon and Steelhead by California Sea Lions in the Area Downstream of Bonneville Dam on the Columbia River, Oregon and Washington, February 29, 2012.

- The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers policy documents and annual reports on sea lion predation

- The 2017 Corps of Engineers report on sea lion predation at Bonneville Dam, Evaluation of Pinniped Predation on Adult Salmonids and Other Fish in the Bonneville Dam Tailrace, 2017

- Booklet from the Council's 2017 Congressional tour on Sea Lions at Bonneville Dam

- All Council news and reports tagged "sea lion"

Notes on chart data:

- Sea lions counted at Bonneville Dam: 1) For 2005, observations did not begin until March 18; 2) In 2015, 2016, 2017, the minimum estimated number of Stellers was 55, 41, 32, which were less than the maximum number of Stellers observed on one day, so the maximum number was used as the minimum. This difference is driven by a focus on California sea lions and a lack of brands or unique markers on Stellers.

- Sea lions branded/removed at Bonneville Dam: For 2008 and 2015, the California Sea Lions removed figures do not include 2 accidental mortalities not listed for removal.

- Spring chinook run and unknown mortality: Measured at tailrace between January 1 and June 15. Passage counts of Chinook salmon includes both adult and jack salmon.

- Summer and winter steelhead at Bonneville Dam: Measured at tailrace from January 1 to June 2. Consumption estimate for 2007 is an expanded estimate, as adjusted estimates did not start until 2008.

- Salmonids eaten by sea lions at Bonneville Dam: Adjusted estimates of consumption from January 1 to June 2