Report: Mid-Columbia Utilities are Meeting Salmon and Steelhead Mitigation Requirements for Dam Impacts

- February 12, 2021

- John Harrison

Five dams on the Columbia River owned by three public utility districts in central Washington are meeting the terms of salmon-survival agreements that require 93 percent survival for juvenile fish migrating downstream past the dams and through their reservoirs, representatives of the districts told the Council at its February meeting.

The agreement stipulates ‘no net impact’ from the dams and reservoirs, and incorporates hatcheries and predator management to mitigate for allowable mortalities – that is, fish losses are balanced with fish mitigation.

For example, the salmon and steelhead juvenile survival standard is 93 percent, meaning that 7 percent mortality is acceptable. The standard for combined juvenile and adult fish is 91 percent, meaning that mortalities cannot exceed 9 percent.

To compensate for mortality caused by either dam and reservoir passage or predation, the districts adjust hatchery operations, improve spawning and rearing habitat in tributary rivers, manage predators, notably fish-eating birds, and invest in fisheries science research.

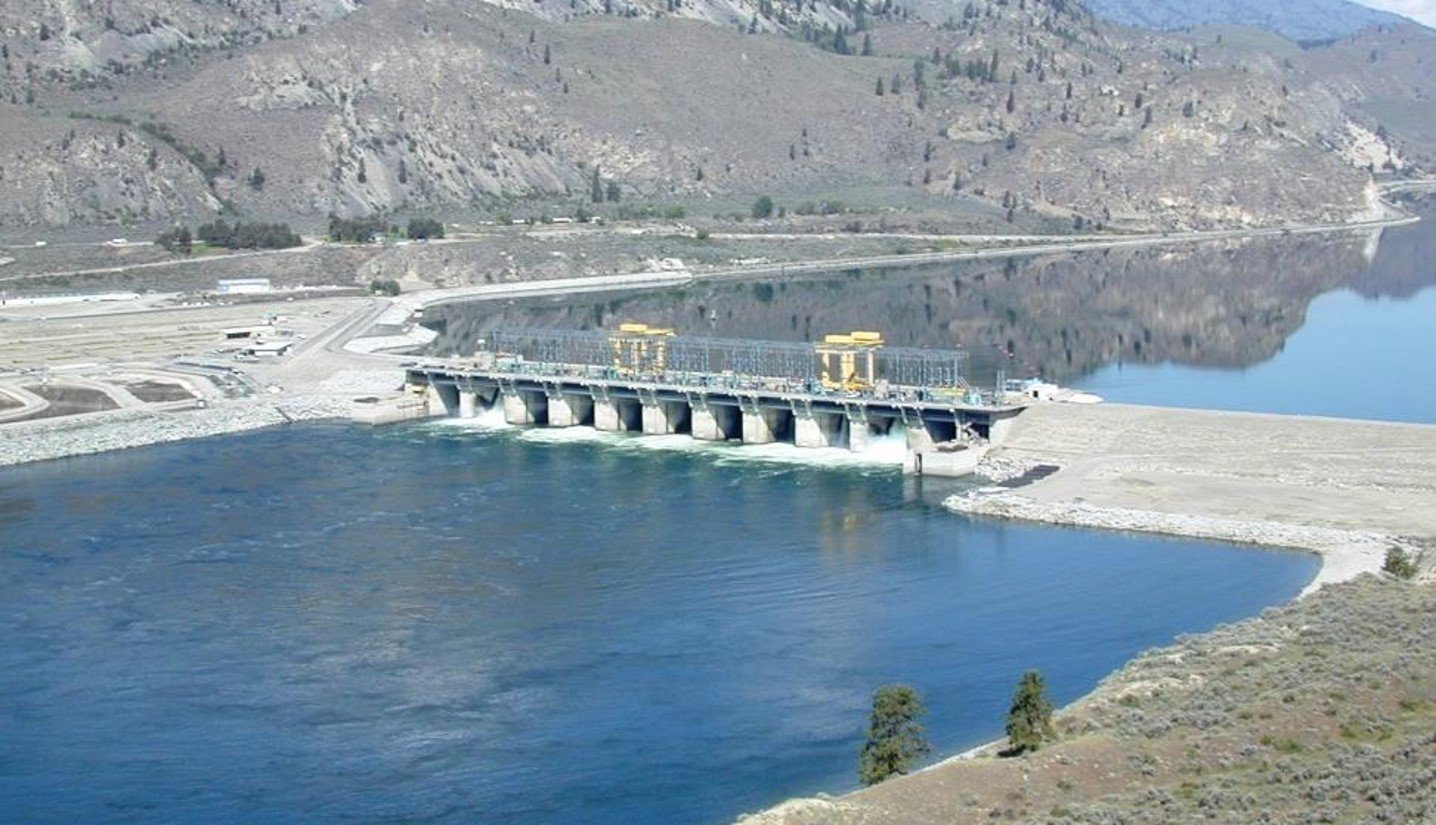

The three public utility districts (PUDs) and the dams they own and operate are Douglas County (Wells Dam), Chelan County (Rocky Reach and Rock Island dams), and Grant County (Wanapum and Priest Rapids dams). Douglas and Chelan have individual habitat conservation plans for their dams, and Grant has a salmon and steelhead agreement that includes Wanapum and Priest Rapids dams. The districts signed the agreements, which last for 40-50 years, in 2002. The five dams and reservoirs include 143 miles of river.

For just one example of outcomes, Peter Graf, a fisheries scientist with the Grant County PUD, said the combined adult and juvenile survival standard for the Wanapum and Priest Rapids projects is 82.8 percent. Monitoring results show the standard is being exceeded – combined survival for steelhead is 85.3 percent, for spring Chinook 86 percent, for summer Chinook, 83.2 percent, and for sockeye, 84.2 percent.

For another example, Lance Keller, senior fisheries biologist with the Chelan County PUD, said mitigation hatcheries annually release nearly 290,000 spring Chinook smolts and about 1.1 million summer Chinook smolts into the Wenatchee, Methow, and upper Columbia rivers. The hatcheries also release about 250,000 steelhead smolts into the Wenatchee River, and about 590,000 sockeye smolts into the Okanagan River in British Columbia. The PUD also contributes to production of coho salmon by the Yakama Indian Nation.

The sockeye production is a success story, largely due to improvements in habitat, artificial production, and Okanagan River water management. From adult fish returns of less than 50,000 – much less in some years – to British Columbia from the late 1970s through 2007, returns jumped up to an average of around 200,000 between 2008 and 2020.

Predation on juvenile fish by fish-eating birds continues to be significant, particularly for upper Columbia steelhead. The PUDs are contributing to an effort to improve management of bird populations on islands in the Columbia and in the Potholes Reservoir to reduce their impact on juvenile fish. Predation on adult fish returning to spawn also is a problem, but the predators are sea lions in the lower Columbia River below Bonneville Dam. Sea lion predation is greatest in the spring and early summer, when upper Columbia salmon and steelhead return. Of the top-four earliest returning populations, three return to the upper Columbia, Graf said.