Snowpack bodes well, for some

Snowpack is good for hydropower this year, but some areas are flooding

- May 09, 2018

- John Harrison

There’s good water news in the mountains of Northern Idaho, Northwestern Montana, and British Columbia as the valley snows of winter melt and the higher mountain snowpack begins to be affected by warming temperatures.

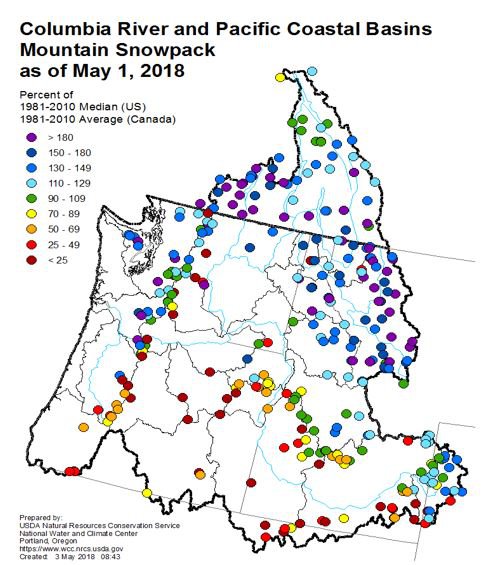

Snow is melting, rivers are rising. The above-average snowpack in the far reaches of the upper Columbia River Basin bodes well for future hydropower generation as the water flows downstream through dams, but it’s not necessarily good news everywhere.

In fact, there is too much of a good thing in Northwestern Montana, as the Clark Fork and Blackfoot rivers are running high and causing localized flooding in and around Missoula, and the Pend Oreille River downstream of Albeni Falls Dam at the outlet of Lake Pend Oreille is at or approaching flood stage. The heavy snowpack in the Clark Fork River drainage, which flows into the northeast corner of the lake, bodes more water to come. Meanwhile, parts of the southern Columbia River Basin, in southern Idaho and southeastern Oregon are drier than average as the result of below-normal rainfall.

It’s a typical pattern and what meteorologists would expect after the dry and warm El Nino condition in the Pacific Ocean during the winter of 2015-2016, and the cool and extremely wet La Nina weather pattern that followed in the winter of 2016-2017, said meteorologist Ron Abramovich of the Boise office of the Natural Resources Conservation Service. Abramovich briefed the Council on current weather trends at a meeting in Boise.

Blue and green dots are good, orange and red dots not so much.

“To understand this year you have to understand the last couple of years,” he said.

The strong La Nina weather pattern of 2016-2017, in which sea surface temperatures along the Equator cool and cause cool, rainy weather in the North Pacific, resulted in more than 40 so-called “atmospheric river” storms that slammed the Northwest with record rain and snow. An atmospheric river is a continuous band of storms sweeping across the Pacific from near Hawaii to the Northwest. These ‘rivers’ were followed last winter by another strong La Nina event, but not as severe as the previous year’s.

“Forty-five atmospheric rivers made landfall on the West Coast,” Abramovich said. “This activity was unprecedented in the 70-year record. The take-home point, he said, is that the ocean and atmosphere are very active following strong El Nino years, when temperatures along the Equator are warmer than normal, causing warmer and drier conditions in the North Pacific.

Rain and snow this past winter left parts of the basin soggy and snowy, and the runoff may be dramatic.

“Rivers are going big in Idaho’s northern basins and parts of Montana, primarily along the Continental Divide,” he said. Last year it was southern Idaho that experienced high water and flooding, and this year, he said, “it’s Montana’s turn.”

He offered some free advice to rafters and kayakers: Don’t, now, unless you like a wild ride. There will be plenty of water for water sports once the rivers calm down, he said.

The precipitation this year and the outlook for irrigation is so favorable that the Idaho Power Company stopped its annual cloud seeding early; irrigation reservoirs in the southern part of the state are full or nearly so.

This year’s runoff provides next year’s surplus, and so it is important to manage water as a resource in wet years to be ready to mitigate impacts in dry years, Abramovich said. While Northwest weather patterns have been normal since February, the trends of recent years are an aberration. “What we’ve seen more recently is the greater degree of climate variability,” he said. “We are living in extremes now.”

The North Pacific Ocean used to oscillate between decades-long periods of warm and cool sea surface temperatures, but more recently the oscillation has changed to become much more frequent – periods of just a few years, influenced by brief El Ninos followed by brief La Ninas.