Warm ocean, small salmon: Why?

- March 07, 2016

- John Harrison

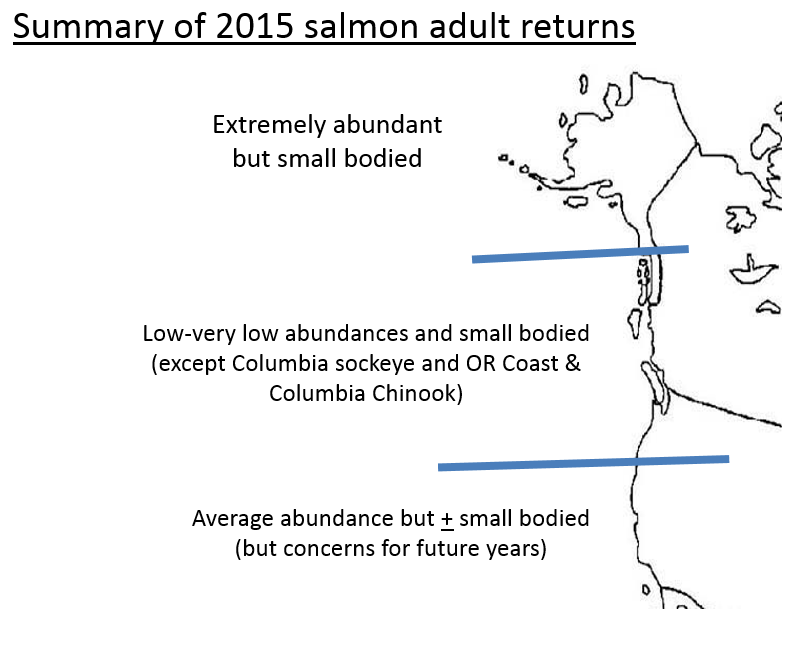

Scientists who study the northern Pacific Ocean are finding some disturbing, if not alarming trends: the ocean has been warming for several years; salmon sampled in 2015 from Alaska to California were smaller than normal; warmer water affects the types and distribution of food species for salmon – in general, there is less nutritious food, and that’s bad news for juvenile salmon as they enter the ocean.

At the same time, though, some salmon runs boomed last year, notably those in Alaska. Others crashed, notably Columbia River coho.

Why?

No one can say with certainty, but research is producing data that will help further understand the inscrutable ocean environment and inform salmon management in fresh water. At a meeting last week of the Council’s Ocean and Plume Science Management Forum, ocean researchers with NOAA Fisheries’ Northwest Fisheries Science Center in Seattle reported their latest findings and discussed the implications with state and tribal fish managers. The Council established the forum several years ago to encourage coordination between ocean researchers and state and tribal fish managers who produce and protect salmon in the hatcheries and freshwater streams where they reproduce.

Map: NOAA Fisheries

Laurie Weitkamp, a research fisheries biologist at the Science Center, noted the apparent effects of the warming ocean on Columbia River salmon: high returns in 2015 of adult Chinook and sockeye, which entered the ocean in 2013 or earlier when the sea was cooler, and low returns of coho adults and jacks, and Chinook jacks, which entered later when it was warmer.

Doug Olson, a supervisory biologist with the Columbia River Fisheries Program Office of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, said it appears that when ocean conditions are poor, salmon tend to return in greater numbers as adults when fewer are released as juveniles. If this is true, he said, the implication is a huge paradigm shift in hatchery management, which traditionally focuses on releasing large numbers of juvenile fish.

He said that if hatchery managers knew two years in advance what ocean conditions will be, hatchery production could be adjusted – some salmon spend up to two years in hatcheries before being released to go to the ocean. But it is difficult, if not impossible, to predict conditions that far in advance with much certainty, the scientists said. There is a lot to learn about all of the ocean and freshwater variables and how they interact. Models based on ocean indicators developed today may not be best for predicting future conditions, Weitkamp said.

It could be true that the size and success of salmon in the ocean is influenced by their sheer numbers and competition for a food base that also may fluctuate in quality and abundance. But trawl data suggests the density of salmon in the ocean already is pretty low, which could be the result of insufficient prey species or some other factors.

“It appears we need to look at this more closely; clearly is something going on, but we haven’t had the resources to look at it in depth,” she said.

Links: