Warm Water Blamed for Huge Columbia River Sockeye Die-off

- July 31, 2015

- John Harrison

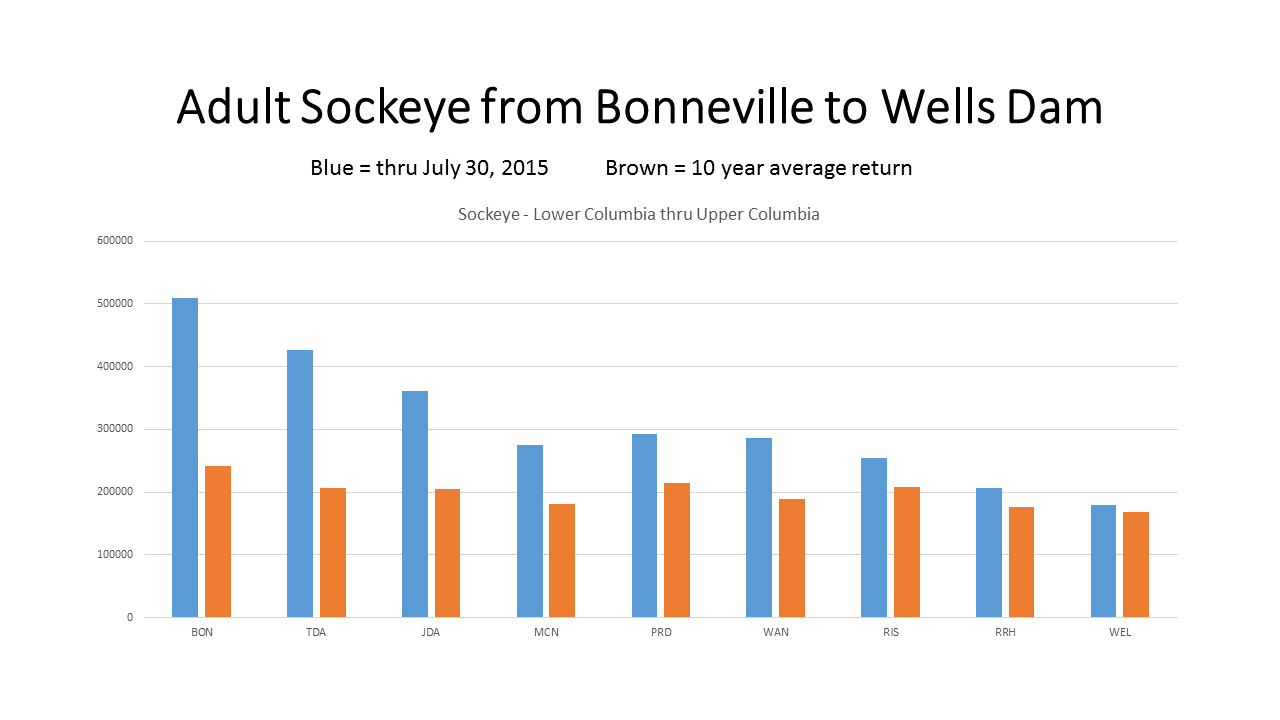

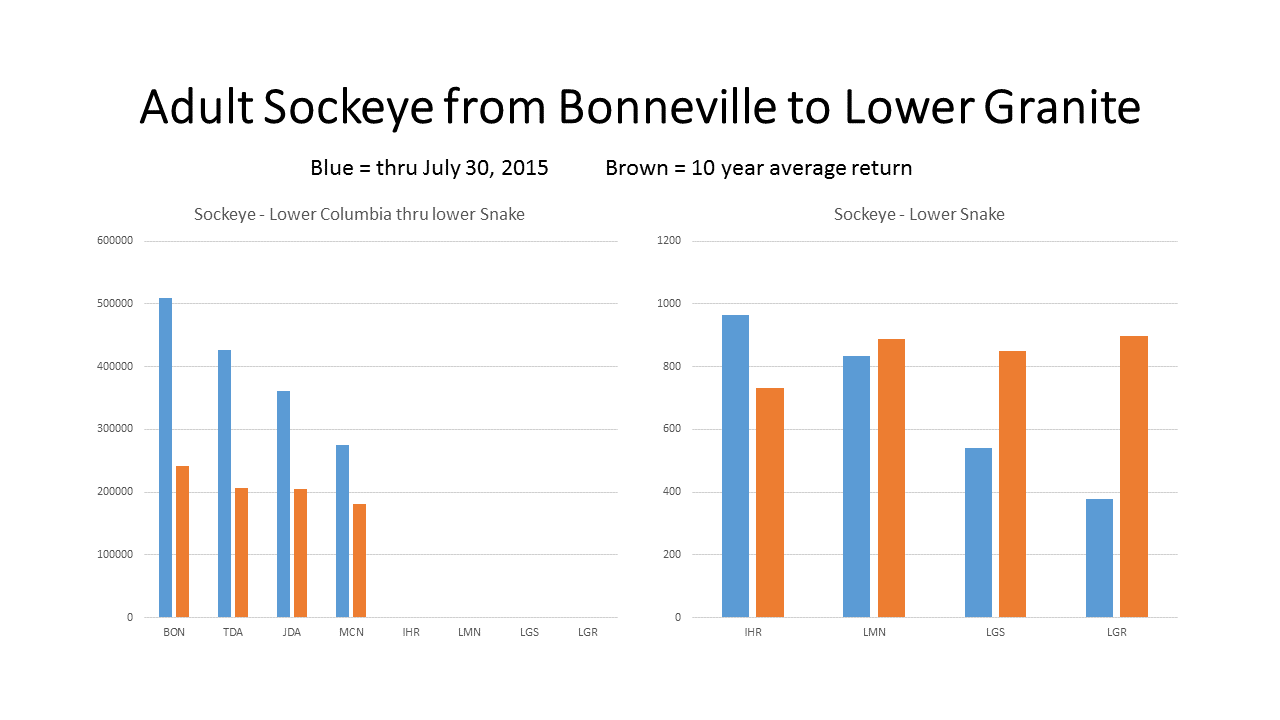

Federal and state fisheries biologists say more than a quarter million Columbia River sockeye salmon have died in the river and its tributaries this summer as the result of unusually warm water prompted by the regionwide drought and hot weather, which has warmed the river to unseasonably high levels for this time of year. The die-off has wiped out half of the anticipated 500,000-fish sockeye run.

Water temperatures in the Columbia have been measured above 70 degrees, and temperatures in tributaries have been higher. Salmon die if exposed to water warmer than 68 degrees for long. Most of the dead and dying sockeye disappeared between Bonneville and McNary Dams.

Biologists expect the sockeye die-off will continue, perhaps reaching as high as 80 percent of the run before the fish reach spawning grounds in north central Washington, British Columbia, and the mountains of central Idaho. Meanwhile, a robust run of fall Chinook – more than 900,000 fish – is forecast for the Columbia system this year. That species typically enters the river from the ocean beginning in late July and early August.

Washington and Oregon fish and wildlife agencies closed all sturgeon fishing in the Columbia on July 18 after dozens of the big, bottom-dwelling fish washed up on river banks dead, many of them near the Tri Cities of Richland, Kennewick, and Pasco. Officials also closed afternoon and evening fishing in many Northwest rivers where low flows and high water temperatures are stressing fish. Columbia river managers are releasing water from upriver storage reservoirs in an effort to cool the downstream water temperatures for salmon and steelhead migrating now and in anticipation of upcoming fall Chinook and coho migrations.

While the 2015 Columbia River runoff volume is not historically low, the problem for fish is the combination of low flows and high water temperatures brought about by summer days of 90-degree and hotter temperatures. The water temperature above Bonneville Dam, for example, has averaged 73 degrees in recent weeks, nine degrees warmer than the average for the same time period over the last five years. For salmon, that’s the difference between lethal and non-lethal conditions.

The near-record low Columbia River runoff in 2015 did not result from a lack of precipitation but from a lack of snow, particularly in the United States portions of the basin. Thus, the winter of 2014/15 could be an anomaly, or it could be an example of what the average winter in the Pacific Northwest could be like by the end of the century, if predictions of an increasingly warmer climate prove accurate.