Will Shad Become the Northwest’s Premier Fish?

A warming climate favors the non-native species in the Columbia River system

- November 28, 2021

- Carol Winkel

Could American shad, a large member of the herring family, worsen the decline of salmon and eventually displace salmon as the region’s iconic fish? That’s the startling possibility posed in a recent report from the Council’s independent scientists presented at the Council’s November meeting.

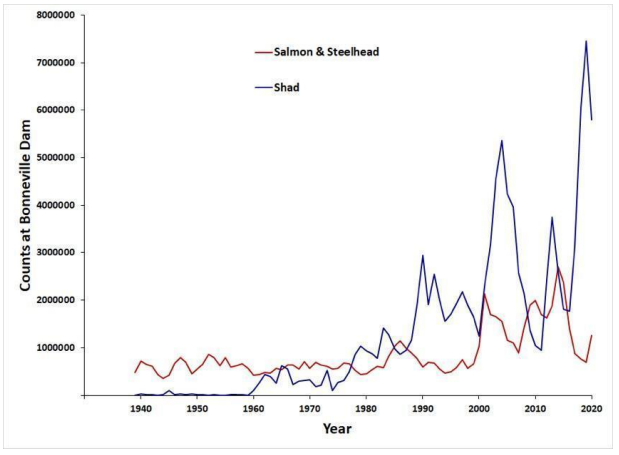

Non-native shad are now the predominant ocean-migrating fish species in the Columbia River Basin, routinely surpassing the total numbers of all returning native salmon and steelhead counted at Bonneville Dam. In some years they are more than 90 percent of recorded upstream migrants. In 2019, more than seven million shad passed above Bonneville Dam by late August, compared with fewer than 250,000 adult wild salmon and steelhead and 450,000 hatchery salmon.

“If the trend continues, there is an emerging risk that the major anadromous fish production of the Columbia River Basin will be for a non-native species rather than salmon and steelhead,” wrote Independent Scientific Advisory Board Chair Stan Gregory. Historically found in the western Atlantic Ocean and the East Coast of Canada and the United States, shad were introduced to the West Coast in the late 1880s because of their popularity in the East where they supported a thriving fishery. But they never really took off with consumers here, who did not have a tradition of eating extremely bony and oily fish. While a healthy food, they are prized today more for their roe than their flesh, although catch-and-release sport fishing is popular in places.

While tribal catches of shad are sometimes sold to wholesalers in smalls quantities, they’re difficult to get to the market quickly. By-catch of salmon in shad fisheries is also a problem. And, unlike salmon, shad aren’t culturally significant for Northwest tribes. For these reasons, there’s currently little interest in shad fisheries for tribes.

Since their introduction, shad rapidly expanded as the hydropower system developed, taking advantage of passage facilities for native salmon species to colonize the upriver reaches of the basin. Biologically, they are well suited to the basin’s rivers, and they thrive in the chain of reservoirs in the Columbia River. They tolerate a wide range of temperature, flow, turbidity, salinity, and other aspects of water quality and quantity; and they produce large numbers of eggs, so can build up populations quickly.

As temperatures increase with climate change, the warmer, more variable conditions are likely to accelerate the decline of native species while favoring non-native species like shad. The lack of a strong fishery to decrease shad numbers makes the problem worse.

As shad populations increase, so do the threats to native fishes, including greater competition for food and critical nursery habitat; predation on salmon young; disease transmission; increasing predator populations; or some combination of these impacts. And the growth of shad populations also risks straining the efforts to stabilize or recover salmon communities.

At such high numbers, shad can interfere with operations to aid adult salmon returns upriver by obstructing the counting of salmon and lowering oxygen concentrations at collection facilities; and complicating accurate identification of migrating salmon and steelhead in fish counting facilities.

Still, the abundance of both shad and salmon depends on the health of the river and reservoirs; the estuary; and above all, the ocean. The winds and currents that create this productivity may become even more erratic because of climate change, so populations of shad, other fishes, and their predators are likely to fluctuate widely and unpredictably.

Despite their abundance in the basin, management agencies have invested little effort to manage or study shad, in large measure because of other critical priorities.

“The consequences of shad for salmon, both pros and cons, aren’t well understood,” noted Independent Science Advisory Board Member Tom Quinn.

Answering questions about the impact of increasing shad numbers on salmon is an important challenge. As the ISAB states, “These emerging issues and potential risks warrant increased attention by resource managers in the Columbia River Basin to address uncertainties about possible shad effects on declining native species and to cultural practices.”