Sea Lion Reports: Stellers Are Staying Longer At Bonneville And Feasting On Winter Steelhead

- May 05, 2020

- John Harrison

Steller sea lions are arriving earlier in the year at Bonneville Dam and leaving later to the point that they live at the dam nearly all year. Even though they consumed fewer salmon and steelhead overall in the spring of 2019 than they did last year, they took a large toll on winter steelhead, an estimated 13.1 percent of the run from November 2018 through March 2019, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers reports in its 2019 annual report on sea lion predation in the tailrace of the dam. The report is posted on the website of the Fish Passage Operations and Maintenance Pinniped Task Group.

The report covers sea lion predation at the dam from January 1 through May 31, 2019, and also, for the first time, during all weeks of the fall and winter months of 2018/2019. NOAA Fisheries asked the Corps to conduct that monitoring to evaluate sea lion predation on fall- and winter-run salmon and steelhead stocks. Sea lion presence has been monitored during the fall and winter months since 2011, but consumption estimates were not regularly described.

Stellers are one of two species of sea lion that prey on adult salmon and steelhead in the Columbia River from the ocean to Bonneville Dam, a distance of about 146 miles. The other is California Sea Lions. Of the two species, Stellers are significantly larger; mature California sea lions can weigh up to 1,000 pounds, Stellers twice that.

While California Sea Lions tend to arrive in the early spring and leave by the middle of June to return to mating grounds off Southern California, Stellers are staying longer and longer. Stellers arrive in the spring, too, but their arrival has been, on average, 11.6 days earlier each year since 2011, according to the report. In 2019, the highest daily count of Stellers in the area below Bonneville Dam, called the tailrace, was 50, but the actual number likely was higher given the limited number of Stellers that have been branded and are therefore individually identifiable. The total number of Stellers was lower in 2019 than in 2018, but unlike Californias, more and more of them don’t leave and come back later in the year (recently, though, some Californias have been returning in the fall, after mating; hence the desire to monitor predation through the fall and winter). They just stay. In fact, Stellers were only away from Bonneville for about six weeks in 2019. This species is now believed to account for more than 92 percent of all sea lion predation on Spring Chinook Salmon, according to the report.

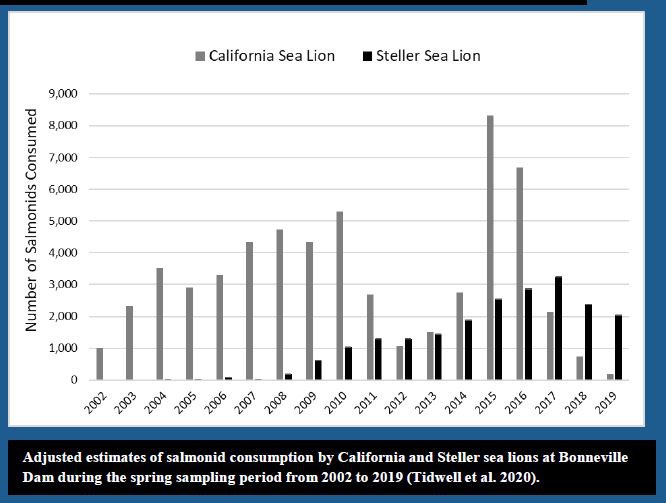

If there is good news for fish, it is that the number of Californias is continuing to go down. The number in 2019 was lower than in 2018, and much lower than the most recent 10-year average. The total daily number was never in double digits, and the maximum daily count was eight. According to the report, there is no doubt this was the result of efforts by state fishery managers to remove offending individuals.

In 2019, The amount of predation on all salmon and steelhead was about the same as in 2018, and about equal to the recent 10-year average, about 2,200 fish, or about 3.3 percent of the runs. But the area immediately downstream of Bonneville is not the only place in the lower Columbia where sea lion predation occurs on adult fish. NOAA Fisheries scientists have documented predation from Astoria all the way to the dam and theorized sea lions may kill as much as 40 percent of the annual Spring Chinook run. However, that research was not conducted in 2019 because of a federal government shutdown in the spring, and it is not being conducted this year because of social-distancing requirements in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. This year, however, the Corps has been able to monitor predation at Bonneville as usual, but the work started only recently when the total number of sea lions exceeded 20, the trigger in law for monitoring to begin.

The 2019 report reflects monitoring of sea lions at Bonneville Dam from mid-July, 2018 through the end of May, 2019. During that time, sea lions killed an estimated total of 3,182 adult salmon and steelhead, 982 during the fall and winter 2018 sampling (July 14-December 31), and 2,201 during the 2019 spring sampling period (January 1 through May 31). Of these, Chinook were hit the hardest, 419 fish in 2018 and 1,974 in the spring.

Sea lion predation on Endangered Species Act-listed species has been documented, including Willamette River Winter Steelhead, Columbia River Winter Steelhead, Upper Columbia Spring Chinook, Snake River Sockeye, and some Chum and Coho salmon. Pacific Lamprey returning from the ocean also are prey for sea lions, as are White Sturgeon. Sturgeon were particularly hard hit by sea lions in the fall and winter of 2018/19, according to the report.

The most aggressive California Sea Lions can be legally removed from the river after a process that includes capturing and branding them. The Northwest states and tribes of the Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission have applied to NOAA Fisheries for permission to enlarge the area where sea lions can be removed, increase the number removed, and make Stellers eligible for removal. A decision is expected in August.

Sea lions were first documented at Bonneville Dam in the late 1980s when California sea lions were sporadically observed preying on Spring Chinook. Steller sea lions were first documented at Bonneville in 2003. Harbor seals also are in the river, and they have been observed preying on fish at Bonneville, but their numbers and the number of fish they took were low.

Data provided by the 18 years of monitoring by the Corps at the dam is used to inform fish management decisions and has contributed to significant changes that are now being realized. For example, the number of California Sea Lions has been greatly reduced as a result of management efforts to remove qualifying animals. However, the number of Steller Sea Lions remains fairly constant and, thanks to the monitoring, information is improving about their impacts on fish.

2019/2020 Update: More Stellers, Fewer Californias

According to a status report posted on the Corps of Engineers pinniped website, Steller sea lions continued to be the dominant pinniped species at Bonneville Dam from July 2019 through May 6 of this year. The Corps issues status updates periodically during the year.

The Corps observes the tailrace below the dam for both the abundance of sea lions and predation on fish by sea lions. Abundance sampling is continuous through the year, but predation sampling does not begin, by law, until the number of sea lions at the dam exceeds 20. This year, that date was April 13.

Travel and work restrictions in response to the COVID 19 pandemic did not affect abundance sampling, but they did affect predation sampling. Data were collected, but have not been analyzed. The results will be reported when the analysis is complete, according to the report.

Steller sea lions have established a near year-round presence at Bonneville. In 2019 they were absent for only about six weeks and were first observed back at the dam on July 17. Only a few were present until the first week of September. From then on there were 10 or more daily. Between July 17 and December 31 the average daily number was 31.8. Interestingly, there were no California sea lions and just two harbor seals at the dam during fall and winter months.

From January 1 through May 6, 2020, the average daily count of Stellers was 9.5 and there were virtually no Californias – the average number was 0.9. The first California sea lion was not observed until March 3; there were no harbor seals. But the Californias did arrive, all at once – 34 were counted on March 31. Then they all left for a week, returning in low numbers beginning on April 7. According to the report, the crowd of Californias may have been following the annual spring runs of Eulachon (Pacific smelt), and as that run dissipated the sea lions left. After that, the highest daily number observed at the dam was seven.

The number of Steller sea lions at the dam in the fall and winter of 2019/2020 was “significantly higher” than the 10-year average, according to the report. During the spring, it was slightly less than the 10-year average. California sea lions simply were not around, compared to the 10-year average – “significantly less” than the 10-year average, according to the report.

Why the big reduction in California sea lions?

According to the report, “the low numbers of [California Sea Lions] near the dam suggests that management has reduced recurrence of offending individuals.”

Management actions by the Washington, Oregon, and Idaho fish and wildlife departments include capturing the most aggressive sea lions and branding them to make them identifiable, and then capturing and removing the branded animals when they are observed continuing to prey on fish. Federal law allows a limited number of these branded animals to be killed.

The report notes that three California sea lions observed at the dam did not have brands, and this “suggests that new animals are still finding the dam.”

Hazing of sea lions from the dam to try to chase them away began March 1; boat-based hazing in the river began in March but was suspended because of social-distancing restrictions in response to the pandemic.