Habitat Restoration to Help Steelhead in the Potlatch River Finds Success

- February 20, 2024

- Carol Winkel

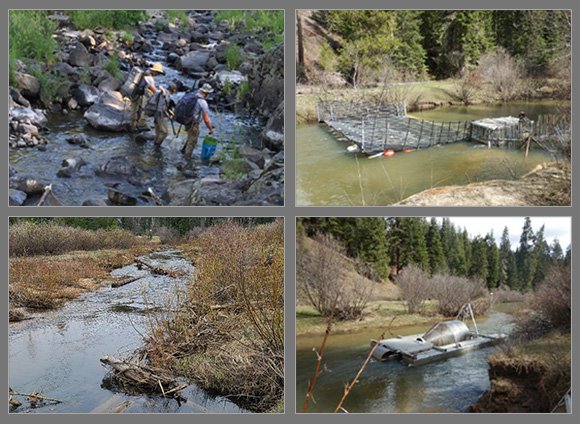

Brian Knoth, fisheries biologist with the Idaho Department of Fish and Game, briefed the Council on their efforts to improve the habitat for steelhead in the Potlatch watershed. (See presentation and video.)

The Potlatch River, located two hours south of Coeur d’Alene in North Central Idaho, is a tributary of the Clearwater River and a key watershed within the lower Clearwater. Spanning about 380,000 acres, it supports the largest spawning area for wild steelhead in the lower Clearwater River.

“The Idaho Department of Fish and Game manages the Potlatch River as a wild steelhead refuge area, which means there is no hatchery supplementation occurring for this population,” said Knoth.

A Changed Watershed

It was once a highly productive system providing abundant numbers of salmon, steelhead, and lamprey to the Nez Perce and Coeur d’Alene tribes.

“Salmon and steelhead populations throughout the Pacific Northwest have declined dramatically from their historic numbers, and today they’re a fraction of what they once were,” noted Knoth.

It’s a well-documented story of human development encroaching on nature. Two industries have had a significant impact on steelhead production in the watershed: agriculture and commercial timber harvest.

Streams were often straightened or re-located, and riparian vegetation and instream woody debris were removed during historic timber harvests in this basin, and agricultural practices have affected stream flows.

Forty percent of the area is devoted to dry land farming in which drain tiles are installed underground to quickly dry out the soil in the spring for crops. But the practice has resulted in powerful spring flow events.

“I think of this part of the watershed as acting like a parking lot,” said Knoth. “In the spring when the rains come, it hits the ground and most of that water runs off very quickly; it flows out the drains, but in this case, the Potlatch River and its tributaries are the drains.”

And these spring flow events have become more powerful over time, creating passage issues for fish migrating upstream to spawn. If the events occur after fish have spawned, the onrushing water can flush fish eggs or newly hatched fry from the system.

Restoration Strategies

The key habitat actions focus on flow supplementation to address low summer base flows; barrier removals to address passage issues; and in-stream treatments to address lack of habitat complexity.

Knoth was especially encouraged by adding water to streams.

“I think this is the strategy that has the greatest potential to influence flow conditions, particularly in certain areas in the Potlatch. We’re able to utilize headwater reservoirs and release water to supplement flows downstream during dry summer month,” said Knoth.

The results of a 2015 pilot project were extremely promising. “We found that by releasing small amounts of water from Spring Valley Reservoir, we were able to maintain perennial flow in upwards of 16 kilometers of habitat downstream of the reservoir—so a pretty massive area,” said Knoth.

“We were also able to rewater an additional 8 to 10 kilometers of habitat in Spring Valley and Little Bear Creeks, which typically go dry every year.”

The water releases also improved water quality downstream in terms of decreased water temperature and improved dissolved oxygen.

“In those two study years, we saw an increase in juvenile steelhead growth and survival,” said Knoth.

This past year, Idaho Fish and Game received a grant to create initial engineering designs to raise the dam height at the Spring Valley Reservoir to store more water to ensure enough cold water to release downstream during the worst drought conditions going forward. The department is also working to secure water rights for the stored water to protect it from unauthorized withdrawals and keep it in the stream for steelhead.

“I’m really encouraged by the progress we’re making, and hopefully it will continue,” said Knoth.

“In reality, it will probably take another couple of years to get the project fully implemented, but if we do, I think it will make a big difference in boosting steelhead production in this area.”