Protecting the Columbia Basin from invasive quagga mussels

- August 21, 2024

- Carol Winkel

At its August meeting, the Council heard updates on the region’s efforts to prevent the introduction of quagga mussels into the Columbia River Basin.

First detected in the Great Lakes in the late 1980s, probably from ship ballast water, they spread quickly to other U.S. waterbodies via contaminated boats and other watercraft. Their microscopic larvae are easily transported downstream in water currents, in water distribution systems, and in watercraft. Once established, they multiply rapidly, clogging a variety of critical waterway infrastructure, from hydropower and municipal water systems to agricultural irrigation and fish screens. The economic and environmental costs to the basin have been estimated to be as high as billions of dollars annually.

The Council’s Fish and Wildlife Program recommends establishing a defensive perimeter to keep invasive mussels out of Columbia River Basin waters and identifies measures for inspection, monitoring, prevention, and the control of aquatic invasive species, including supporting regional efforts on early detection and rapid response.

Nic Zurfluh, invasive species bureau chief for the Idaho State Department of Agriculture and Justin Bush, aquatic invasive species policy coordinator for the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife provided updates on their states’ efforts to address the challenge.

Last September, quagga mussel larvae were detected in the Snake River near Twin Falls, Idaho during routine monitoring conducted by the Idaho State Department of Agriculture, the first time they had been found in the basin. Since then, efforts have increased in key areas: prevention, readiness response, early detection and monitoring, research, and communication.

“Our number one goal is to prevent the establishment of quagga mussels in the Columbia River Basin,” said Bush. “We do this through a comprehensive and coordinated watercraft inspection program across the western United States.”

Bush noted the need to keep in mind the pathways for their introduction besides water currents.

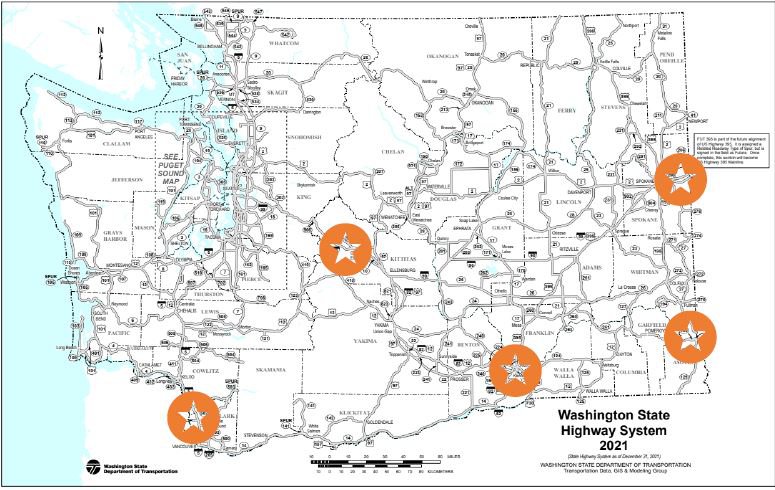

“Just this year, we inspected over 24,000 watercraft coming into the state and seven were found to have invasive mussels. It’s not just downstream movement, but introduction from human movements and activities,” said Bush.

| 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024* | |

| Operational days | 532 | 940 | 1,412 | 1,501 | 863 |

| Watercraft inspected | 31,651 | 55,812 | 51,942 | 58,618 | 24,894 |

| Mussel-fouled watercraft | 23 | 39 | 25 | 25 | 7 |

| * January 1 - July 16, 2024 | |||||

In Idaho, which was ground zero last fall, Zurfluh described the state’s rapid response focused on notifying affected entities, implementing containment measures, conducting surveys to determine the extent of the problem, and exploring treatment options.

Since the outbreak, Zurfluh noted that keeping quagga mussels out of the basin will be a year-round, full-time effort.

“We’re moving from prevention to prevention and containment, and making sure we’re getting the message out to the public to clean, dry, and drain your watercraft.”

Protecting the basin depends on a constellation of federal, state, tribes, municipal, and private entities working in coordination.

“We rely heavily on our many partners to coordinate our efforts to get the word out and implement the critical work,” said Zurfluh.

Read more: