Council briefings on Fish and Wildlife Program continue in advance of deadline for recommendations

- March 21, 2025

- Kym Buzdygon

In case you missed it: Previous briefings on the Fish and Wildlife Program included an overview of hydroperations in January (watch video | read presentation) and a review of Program strategies in February (watch video | read presentation). Learn more and submit your recommendation at nwcouncil.org/amend.

April 17, 2025, is currently the deadline to submit recommendations to amend the Fish and Wildlife Program. A special Council meeting is being held on March 27, 2025, at 12:30 pm (PDT)/ 1:30 pm (MDT) for the Council to discuss and possibly decide on an extension to that deadline.

At its March 12 meeting, the Council heard additional briefings on the 2014/2020 Fish and Wildlife Program as the deadline nears for state and federal agencies, tribes, NGOs, the public, and more to submit recommendations.

AEERPS

The first part of the briefing covered an important provision of the Northwest Power Act (the Act) that states, “The [fish and wildlife] program shall consist of measures to protect, mitigate, and enhance fish and wildlife affected by the development, operation, and management of such facilities while assuring the Pacific Northwest an adequate, efficient, economical, and reliable power supply.” An adequate, efficient, economical, and reliable power supply (often shortened to the acronym AEERPS), might seem like it belongs exclusively to the power planning side of the Council’s work. But, as General Counsel John Shurts explains, this is one of the places where Congress intended the Council to consider the link between the fish and power side. At the same time, the Act “doesn’t give you a lot of guidance on how [or] what to do with it...And we’ve had to wrestle with that over the years,” he said.

The Act does not make explicit how to define those terms or how to demonstrate that determination, particularly as it relates to the Fish and Wildlife Program. Shurts went on to explain that the Act does make clear that it is not intended to be a balancing effort. Rather, the Council is expected to achieve both objectives. The Act and legislative history also focuses on the regional power system, not exclusively the Bonneville-managed part of the federal hydrosystem, and expects some degree of impact from the fish and wildlife program on system generation and costs.

Due to a situation in the early 90s that combined increasing costs for BPA, uncertainty on how the agency would compete in emerging wholesale power markets, and expanded fish and wildlife protection and mitigation spending following the first ESA listings of Snake River salmon in 1991-92, the 1994 Fish and Wildlife Program was the first in which the Council really took on the task of defining and applying the AEERPS standard. A collaborative effort resulted in the addition of Appendices B and C to the Program, crafting an approach for analyzing the potential impacts of the Fish and Wildlife Program on the power system and on Bonneville in the context of other effects as well.

Shurts noted that this analysis is necessarily tentative, as the follow-on power plan will analyze the effects on the adequacy and economics of the region’s power supply. The Council then crafts a resource strategy for the power plan that adds the cost-effective conservation and generation resources necessary to maintain an adequate and affordable system and implement the operations to benefit fish and wildlife in a similarly reliable manner. Bonneville then has the responsibility under the Act to add resources consistent with the power plan to meet load demands and to assist in implementing the operations to benefit fish.

The Council has used the same general approach for analyzing the AEERPS standard in subsequent Programs, and staff recommends doing so again in the current amendment process. Over the life of the Program, a significant suite of hydro operations has been built up to benefit fish. Contemporary issues that may come up during the amendment process and affect system operations could include the issue of hydrosystem flexibility and daily ramping and effects on fish and wildlife, impacts on reservoir operations from the provisions of the Columbia River Treaty Agreement in Principle, and more.

Council members discussed a range of related questions and concerns, including whether and how litigation has contributed to defining the AEERPS standard, what role power markets might play in future decisions, and how various costs and benefits are considered across the system.

“The Act assumes that you will do both, and you can do both. You can have the system change in ways that’ll be good for fish and wildlife and yet, through the right resource strategy, you’ll be keeping the system adequate [and] reliable,” reiterated Shurts. “And we have...stretched the value of the system [through measures for fish and wildlife and energy efficiency] and it’s worked. We do have a system that’s adequate, and, looking forward, reliable, and that remains economical for the region. It’s a challenge every time we go through this cycle, but every time we do, we learn more."

Adaptive management

Fish and Wildlife staff presented on the adaptive management part of the Fish and Wildlife Program as part of an ongoing review of the existing 2014/2020 Fish and Wildlife Program. They explained that there is an inherent tension between needing to implement on the ground work in sometimes limited timeframes, with the need to do research, monitoring, and evaluation to ensure that goals are being met. The adaptive management cycle provides a structure to iteratively improve management actions and outcomes. True adaptive management encompasses more than “learning by doing”. It involves the multiple steps of “learn”, “plan”, “do”, “evaluate”...and “adjust”.

Adaptive management has a long history in the Program. Kai Lee, a Council member in the 80s, was an early proponent of adaptive management as a policy framework for the Fish & Wildlife Program. Adaptive management is important because the Columbia River Basin is large and complex, with unique mitigation needs. Conditions continue to change, and new critical uncertainties emerge. Some examples of adaptive management under the Program that have led to improved management and implementation include fish tagging technology, fish passage improvement, hatchery review and reform, and habitat planning. Adaptive management exists at multiple scales in the Program, including in-season decision-making and project review and adjustment.

“Projects often include decision points, where we have time to circle back and see how things are working, and maybe make adjustments,” explained Fish and Wildlife Program Scientist Kate Self.

“As scientists, we know that uncertainty exists. It exists in power planning, it exists in fish and wildlife mitigation. This is a normal part of management and it’s a normal part of the scientific method,” added Biologist for Program Performance Kris Homel. “We have an adaptive management strategy that organizes our approach to addressing uncertainties in a thoughtful manner so that we can do better on the ground management in the future...Sometimes, when people hear uncertainties, they think it means we don’t know what to do. But really it means we plug uncertainty into a process to continue to make better decisions.”

The current Program funds the critical work of assessing, monitoring, effectiveness, research, data management, reporting, and evaluation.

Council members asked about how to right size the balance between research and on-the-ground work, given the constraints of time and funding. Staff members discussed the critical progress that the Program has made over time in baseline understanding and identification of critical uncertainties, to better inform and sharpen research in the future. Staff and members also discussed the possibility of reviewing and updating the 2017 Research Plan.

Subbasin Plans

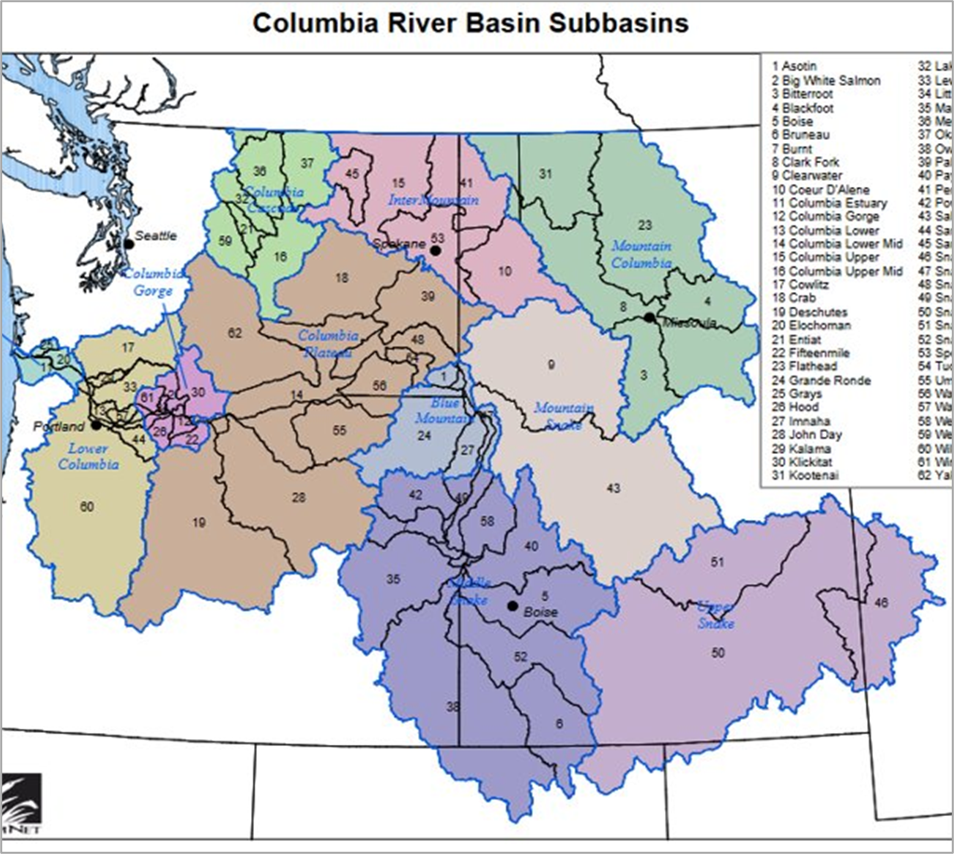

The final part of the briefing covered subbasin plans. There are 59 subbasin plans, intended to identify priorities and coordinate efforts in specific subbasin areas through a bottom up, locally driven process based on that subbasin’s specific ecology, geology, communities, and priorities.

Subbasin plans were developed largely in response to an Independent Science Group (precursor to the ISAB) review in the mid 90s that resulted in the Return to the River report. The report said that while the Program contained good measures, it lacked a solid framework to guide decision making and link actions to goals and objectives, particularly at a more regional level. At the same time, the ISRP project review also found that there needed to be more context for why certain habitat projects were being proposed, with a link between the projects and the problems they were trying to solve. In that sense, the subbasin plans were intended to provide a solid foundation under the work that was already occurring, in addition to guiding future work.

Fish and Wildlife Director Patty O’Toole also clarified that subbasin plans were intended to build a foundation for off-site mitigation, provide the scientific underpinning, and explain why certain actions and projects were the right things to do in a particular moment, not put the onus of fixing all the potential problems that were identified in a subbasin on hydrosystem mitigation.

Extensive engagement with state and federal agencies, tribes, nonprofits and other entities in the early 2000s led to the scientific review and Council adoption of most subbasin plans in the 2003 Program. Plans included a technical assessment, an inventory of existing activities, and a 10-15 year management plan. In addition to being used to implement the Council’s Fish and Wildlife Program, plans were used for additional purposes including as a guide for planning ESA recovery efforts and other watershed and restoration work.

A 2011 survey showed that the subbasin plans were largely considered helpful for preparing project proposals, identifying priorities, and providing general subbasin information. However, issues with the plans included a lack of updates for management plan sections, tension over responsible parties, and a feeling that they were too broad.

Updating subbasin plans was designated an emerging priority in the 2014 Program. Director O’Toole shared that there has been interest in updating some of the subbasin programs and/or adopting updated plans into the Program, but no updated plans have currently been received.