Independent science panel: Habitat projects show benefits to Columbia Basin fish & wildlife, while lengthy time periods needed

Barrier removal, large wood additions highlighted in suite of habitat restoration projects

- July 24, 2025

- Peter Jensen

At July’s Council meeting in Portland, members of the Independent Science Review Panel discussed results and key findings from the Habitat Retrospective Report that the ISRP published in July. This report reviewed the Fish and Wildlife Program’s habitat restoration work in the Columbia River Basin over the past several decades.

Rich Carmichael, the ISRP Chair and formerly with Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, was joined by Kurt Fresh, the ISRP Vice Chair and formerly with NOAA Fisheries’ Northwest Fisheries Science Center, Kurt Fausch, professor emeritus with Colorado State University, Stan Gregory, professor emeritus with Oregon State University, and Erik Merrill, the Council’s Independent Science Manager (read presentation | watch video).

Target species that benefit from habitat restoration in the Council’s Program include anadromous fish like salmon, steelhead, and Pacific lamprey, as well as resident fish such as cutthroat trout, and bull trout. Wildlife also benefit from these improvements.

As part of their assessment, the ISRP concluded that habitat restoration measures will benefit anadromous as well as resident fish, Fausch said. They tracked eight common methods at reach- and watershed-scales across the Basin:

- Barrier removal

- Adding large wood to make habitats more complex

- Reconnecting floodplains

- Riparian restoration

- Dike-breaching and tide gate management

- Augmenting flows

- Cold-water refuges

- Wildlife habitat restoration

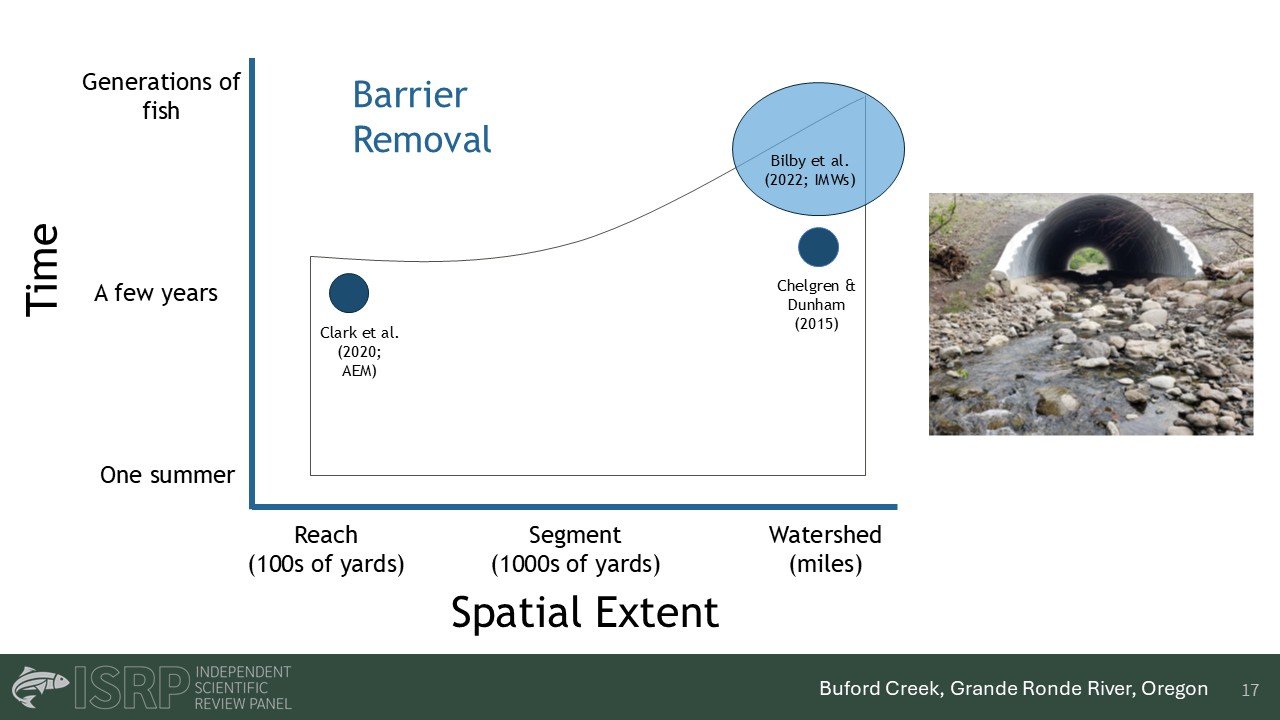

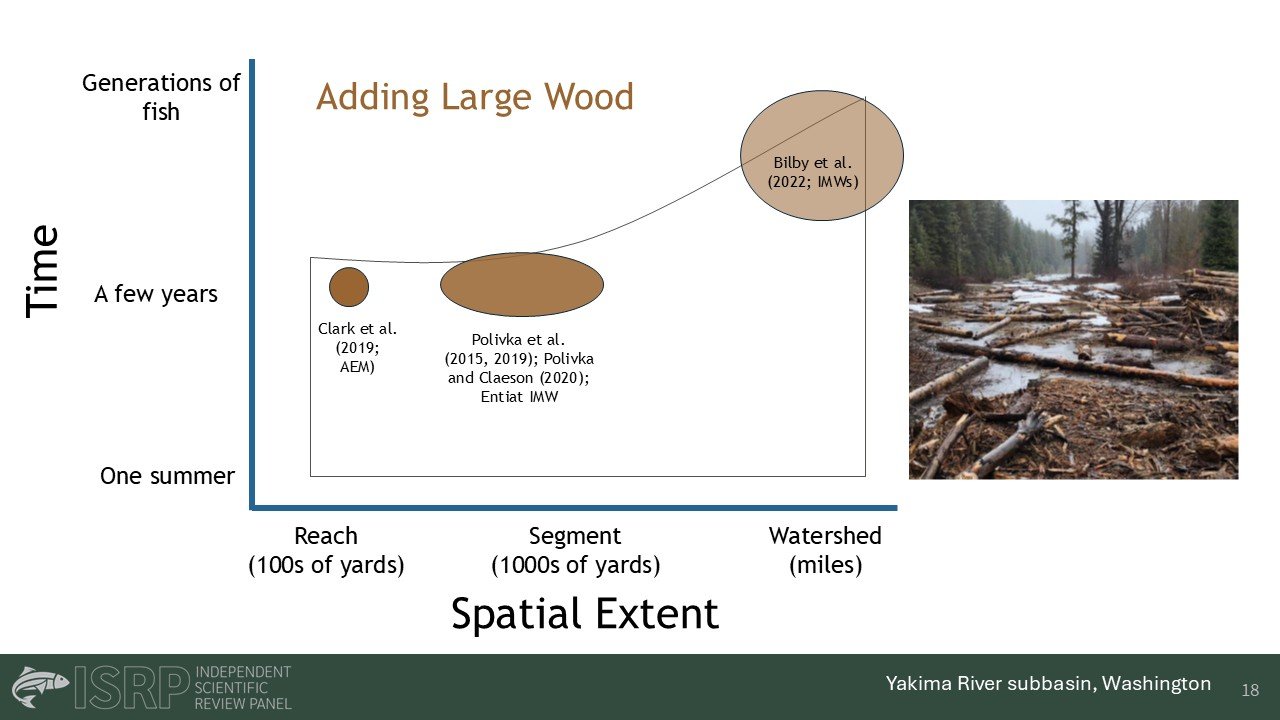

The evaluations that the ISRP reviewed were conducted over a wide range of times and spatial extents. At the reach and segment scale, the project evaluation covered between hundreds to thousands of yards of habitat improvements. Watershed-scale evaluations covered miles. Times ranged from a few years to generations of fish.

Fausch explained two examples of the ISRP’s analysis focusing on barrier removal and adding large wood.

Barrier removal

He explained that tens of thousands of barriers impact fish in the Columbia Basin because they block access to upstream habitats. Removing barriers is among the most common restoration methods.

For example, in the Upper Columbia, the Salmon Recovery Board removed about 100 barriers by 2012, which opened up almost 300 miles of blocked habitats. A 2020 study measured fish above and below 32 barrier removal sites over a 14-year period. They found that juvenile salmon and steelhead had swiftly established themselves, showing the projects were successful.

A 2022 study reviewed by the ISRP analyzed barrier removals in 10 intensively monitored watersheds over multiple generations of fish. It found fish established themselves upstream in nine of these watersheds, and measured increased juvenile or smolt density, survival, or growth in eight of the 10 watersheds.

“Overall, we concluded that barrier removal was among the most common and most successful of habitat restoration methods,” Fausch said.

Large wood additions

The Fish and Wildlife Program has been adding large wood to create pools and make habitat more complex since its beginning in the early 1980s. In the Upper Columbia, these comprise one-fifth of the habitat restoration projects. 500 structures created pools in 22 miles of streams.

A 2019 study covering several years analyzed 29 projects that were completed within the past five to six years, on average. The study found that pools and habitat complexity increased by 20-40% and doubled to nearly tripled the counts of juvenile Chinook, coho, and steelhead, on average.

A 2022 study spanning multiple generations of fish analyzed large wood that was installed in 12 of 13 intensively monitored watersheds. Tallies showed increased habitat complexity in eight of the 12 watersheds, and positive responses by juvenile or adult fish in 10 of the 12. These additions of large wood often happened in concert with other habitat restoration efforts, like barrier removal.

Program evolution and key takeaways

Gregory noted a shift in projects that the Fish and Wildlife Program has undertaken over the past 40 years. One major advancement has been the improvement in the goals and objectives in these projects, developing targets with specific timelines for achieving them. Early projects focused on local sites and were limited in their scale. That’s changed over the years. Projects have evolved in their complexity and increased their spatial scales, while coordinating with other projects to address multiple impacts.

“Quite often the factors that cause habitat degradation are not a single factor, and they’re not simply addressed by one action,” Gregory said. “We’ve seen the development of more complex designs to address multiple factors…over larger spatial scales, integrating those different restoration actions, and cooperating with other projects. That’s a major strength, and we’re increasing the scale of restoration.”

He also noted that the Program has shifted to focus on restoring ecological processes and function, particularly since the 2000 F&W Program. Other improvements in planning and prioritizing included:

- Increasing and effective use of models such as habitat and life cycle models;

- More rigorous analysis of limiting factors and density dependence;

- Use of landscape frameworks and strategic planning;

- Use of Indigenous knowledge, such as the First Foods Planning Framework used in tribal restoration efforts.

In conclusion, the ISRP report found significant improvement over more than 40 years of F&W Program habitat protection and restoration work, especially for planning and prioritization of projects and actions. Restoration methods have improved due to monitoring and process-based approaches.

Research, monitoring, and evaluation challenges remain, however, despite significant Program efforts. The ISRP found the Council’s recent efforts and strategy to be promising, but research, monitoring, and evaluation is still needed at large physical and biological scales. The ISRP also found a need to synthesize information across studies, especially for intensively monitored watersheds. Decisions and analysis on how to prioritize actions and evaluate success must account for an array of challenges, such as climate and landscape change.

Based on the retrospective report’s findings, Gregory said the ISRP recommends that the Fish and Wildlife Program’s habitat restoration efforts:

- Continue to support analyses of limiting factors and density dependence as critical components of habitat restoration planning and prioritization, including life-cycle modeling;

- Explore the potential use of habitat and life-cycle models for strategic analyses and general restoration planning for projects that lack necessary information or support for detailed project-scale modeling;

- Incorporate process-based restoration and the assessments necessary to support it in planning and prioritization;

- Determine where watershed-level assessment and coordination approaches are effectively guiding restoration and develop additional subbasin assessments to fill gaps and better represent the diversity of landscape types and ecoregions in the Basin.