Fish-eating Birds Kill Half, Or More, Of Upper Columbia Steelhead Smolts, Research Shows

- February 19, 2020

- John Harrison

Fish-eating birds are responsible for half or more of the deaths of juvenile Upper Columbia steelhead, an ESA threatened species, before they enter the ocean, 12 years of research indicates.

The Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission (CRITFC) is trying to raise public awareness of the alarming problem, CRITFC’s executive director told the Council this month.

According to a report to the Council last September by bird researchers from Oregon State University and Real Time Research, Bend, Oregon, “… the cumulative effects of avian predation on smolt survival can be substantial, with avian predation accounting for more than 50 percent of all [upper Columbia steehead] smolt losses during out-migration.”

While the problem of marine mammals eating adult salmon and steelhead as they migrate upriver from the ocean every spring has attracted a lot of attention, the problem of birds eating juvenile salmon and steelhead as they migrate downriver to the ocean is not as well known. Research shows that while birds eat juvenile fish of all species, one species in particular – Upper Columbia Steelhead, an ESA-threatened species, is particularly hard hit. Between 2008 and 2019 birds killed more steelhead from the upper Columbia region than all other causes combined.

“We’ve been working to try to bring more attention to avian predation,” said Jaime Pinkham, CRITFC executive director. “It’s one of the issues that people are becoming more and more aware of; people need to understand the magnitude of the problem.”

Blaine Parker, a CRITFC biologist, said juvenile salmon and steelhead face a gauntlet of predatory birds literally from the moment they enter the Columbia.

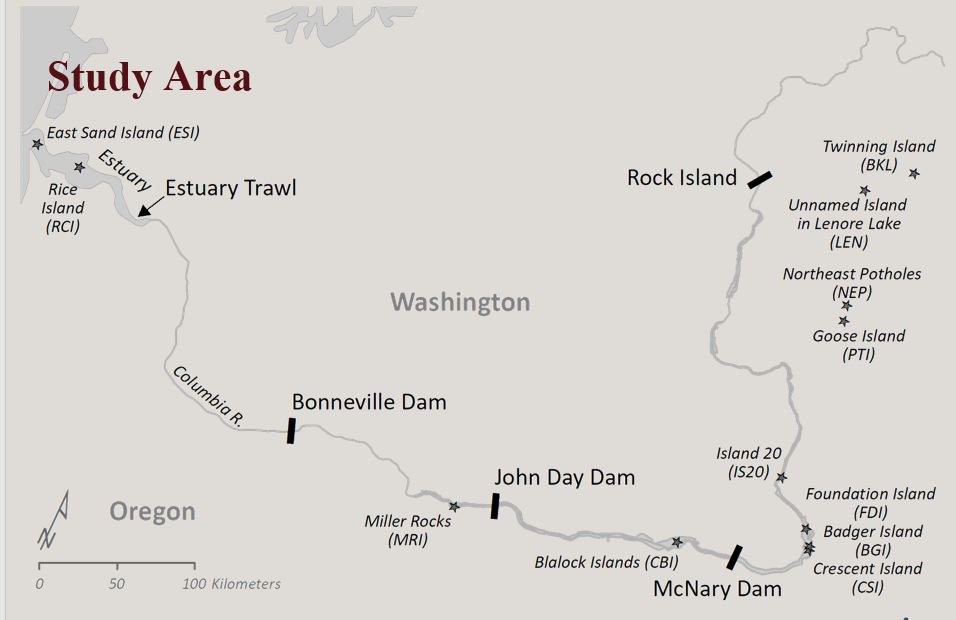

“Way up in the basin fish are exposed to avian predation, primarily by Caspian terns but also by gulls,” he said. “As they move down the system they run into more terns, more gulls, pelicans, cormorants. After hundreds and hundreds of miles of this they finally are exposed to the worst of the gauntlet, which is right when they hit the salt, in the estuary.”

He said the tribes are particularly concerned about steelhead, as the tribes’ fishing seasons in the Columbia are affected by the number of returning adult steelhead.

Last September, Dan Roby of Oregon State University and Allen Evans of RealTime Research, reported a summary of 11 years of their research, 2008-19. Roby said they “discovered to our surprise that avian predation is a major source of smolt mortality” on juvenile upper Columbia steelhead. For a number of ESA-listed stocks of Columbia Basin Chinook salmon, cumulative avian predation rates are much lower than for upper Columbia River steelhead. Juvenile steelhead in general have been shown to be more susceptible to avian predation, especially predation by Caspian terns, than other species of Columbia Basin salmonids.

Bird predation is an important problem for juvenile salmon and steelhead in the Columbia River system. Compounding the problem is the fact that the spring and early summer migration of these fish coincides with the birds’ nesting season. So, parent birds are always searching for food for themselves and their chicks. Smolts migrating downriver from the Snake and upper Columbia rivers pass through as many as 14 foraging areas.

Additionally, while the number of fish-eating birds in the Columbia River estuary has been significantly reduced in some areas since 1997, when a regional effort began to curb their impacts, the population still is larger than fish managers would like. In 2019, a large population of fish-eating Double-crested Cormorants left an island in the estuary where they had been nesting, after being harassed and even shot, and moved to two Astoria-area bridges – the Astoria-Megler Bridge and the bridge over Young’s Bay. From these nesting sites, the birds continue to feed on juvenile fish, including salmon and steelhead from upriver. Meanwhile upriver, Caspian terns nesting on Crescent Island in the Columbia near the mouth of the Snake River, and at Goose Island in Potholes Reservoir near Moses Lake, Washington, kill large numbers of smolts every year. Harrassing birds where they nest simply moves them from one place to another – like a game of whack-a-mole, Parker said :“you chase birds from one location to another; they’re not being removed, they’re just getting bounced around.” Caspian terns in the mid-Columbia area, harassed off their usual breeding island, simply moved downriver onto islands within the Umatilla National Wildlife Refuge, where they cannot be harassed.

Ultimately, Pinkham said, the problem is that bird protection is not balanced with salmon restoration.

“Missions and responsibilities need to be aligned, and a basin-wide strategy is needed,” he said, adding it is important to the tribes that the maximum number of fish that can reach the ocean actually reach the ocean.

What to do?

New legislation may not be needed because there is flexibility to address the problem in current law, Pinkham said. For example, he said, the federal government may be willing to balance federal laws that protect species, like the Endangered Species Act (Upper Columbia Steelhead) and the Migratory Bird Treaty Act (Caspian Terns).

“Our aspiration this year is to form a coalition around building an avian predation plan,” Pinkham said. “It will be a tribal and state partnership.”

He said he recently had an encouraging meeting with the assistant director of the federal Migratory Bird Program in Washington, DC, and is planning follow-up discussions. Pinkham said CRITFC volunteered to host a meeting of co-managers of fisheries and birds last fall.

Bird Researchers' Report Documents A Huge Problem For Steelhead

In its 2019 annual report on bird predation on juvenile fish in the Columbia Plateau region of Washington, bird researchers from Oregon State University and Real Time Research, Bend, Oregon, write that steelhead smolts appear to be particularly targeted by birds. Summarizing 12 years of research, the scientists wrote:

Results indicated that avian predation was often the single greatest source of mortality for steelhead during out-migration from Rock Island Dam to Bonneville Dam, with bird predation accounting for more than 50 percent of all mortality sources in 10 of the last 12 years (2008-2019), including in 2019. Estimated steelhead smolt losses to piscivorous colonial waterbirds were greater than direct losses associated with dam passage, predation from piscivorous fish, mortality from disease, and all other remaining mortality factors combined.

Even after passage through the impounded sections of the middle and lower Columbia River upstream of Bonneville Dam, the impact of piscivorous colonial waterbirds on survival of steelhead smolts in the free-flowing section of the Columbia River downstream of Bonneville Dam was substantial, with Caspian terns and double-crested cormorants nesting on East Sand Island annually consuming upwards of 28 percent of available steelhead smolts in the estuary. Results indicate that although progress has been made to increase steelhead smolt survival by decreasing Caspian tern predation between Rock Island Dam and McNary Dam, avian predation continues to be a dominate source of smolt mortality in the Columbia River Basin.