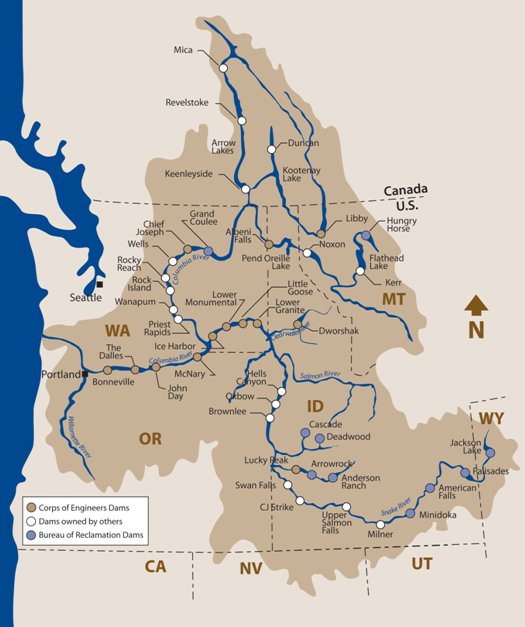

The Columbia is one of the great rivers of North America. Beginning at Columbia Lake, British Columbia, the main branch of the river travels over 1,200 miles through fourteen dams before reaching the Pacific Ocean a hundred miles downstream from Portland, Oregon. Fed mostly by melting snow, the Columbia River drains an area of about 259,000 square miles in a basin that spans seven U.S. states and a portion of southeastern British Columbia. Major tributaries feeding the Columbia include the Kootenai, Flathead, Clark Fork/Pend Oreille, Kettle, Okanogan, Methow, Spokane, Wenatchee, Yakima, Snake, Clearwater, Salmon, Owyhee, Grande Ronde, Walla Walla, Umatilla, John Day, Deschutes, Hood, Willamette, Klickitat, Lewis, and Cowlitz rivers. The largest tributary, the Snake River, drains an area of nearly 110,000 square miles or almost 50 percent of the U.S. portion of the basin. In all, the Columbia and its tributaries run through climatic conditions and topography as varied as any river in the world -- from alpine to desert to rainforest.

The Columbia River is home to six species of Pacific salmon: Chinook, coho, sockeye, chum, and pink salmon, and steelhead. The basin’s salmon and steelhead runs were once among the largest in the world, with an estimated average of between 10-16 million fish returning to the basin annually. For thousands of years, the tribal people of the basin have depended on these salmon runs and other native fish for physical, spiritual, and cultural sustenance. Commercial and sports fishing, and recreational, aesthetic, and cultural considerations endear salmon and steelhead to millions of other residents and visitors. Many animals, including bald eagles, osprey and bears, also rely on fish from the Columbia River and its tributaries to survive and feed their young.

Salmon and steelhead runs, along with other native fish and wildlife in the basin, have declined significantly in the last 150 years. Recent years have seen some improvements in the number of adult salmon and steelhead passing Bonneville Dam; however, many of these are hatchery fish. Many human activities contributed to this decline, including land and water developments across the region that blocked traditional habitats and dramatically changed natural conditions in rivers where fish evolved.

These developments included the construction of dams throughout the basin for such purposes as hydroelectric power, flood control, commercial navigation, irrigation, and recreation. Fourteen of the largest multi-purpose dams are on the mainstem Columbia; the mainstem Snake River adds another dozen major projects. Water storage in the Columbia River totals approximately 30 percent of the average annual runoff, which fluctuates from year-to-year depending on the snowpack. With its many major federal and non-federal hydropower dams, the Columbia and its tributaries comprise one of the most intensively developed river basins for hydroelectric power in the world. Hydroelectric dams in the basin produce, under normal precipitation, about 41 percent (14,000 average megawatts) of all the electricity generated in the Pacific Northwest.

Dams control how water flows in the modern Columbia River -- storing runoff, reducing flood flows, shifting flows from the natural spring/early summer peak to fall and winter to generate electricity for the region’s peak electricity demand, and blocking, inundating, or reconfiguring major river reaches. These river developments support the region’s economic prosperity while having substantial adverse effects on the native anadromous and resident fish and wildlife of the basin. To address these effects, and also to provide for coordinated, region-wide planning to meet future demand for electricity in the Pacific Northwest, Congress passed the Pacific Northwest Electric Power Planning and Conservation Act in 1980.