The history of the Columbia River is rich with people who had extraordinary vision and, importantly, the ability to inspire others. To some observers they were prescient, and to others they were simply crackpots with crazy ideas. Each, however, had a particular genius, a base of unique knowledge or ability, and charisma.

Some are major figures in Columbia River history, and others aren’t. Some acted solely for personal gain, others saw the river in a broader context as a servant of Northwest society. Some succeeded, others failed. Each, however, saw future possibilities that many of their contemporaries didn’t see — an Eden at the end of a long trail west, river transportation, hydropower, railroads, irrigation, economic growth, reduced hunger and improved living conditions. When many of the most important events in Columbia River history are traced to their roots, inevitably these people, and others like them, stand out. Here is but a sampling: Hall Jackson Kelley, promoter of westward emigration; Nathaniel Wyeth, pioneer Columbia River entrepreneur; U.S. Army Lt. John Mullen, surveyor and road builder; Sandford Fleming, Canadian railroad surveyor and designer; William Baillie-Grohman, canal builder who linked the Kootenay with the Columbia; Sam Hill, road builder and businessman; Rufus Woods, newspaperman and promoter of Grand Coulee Dam; Herb West, promoter of Columbia and Snake river navigation; Woody Guthrie, Columbia River balladeer; Sophie Pierre, Canadian salmon advocate; and Mark Hatfield, Oregon governor, U.S. senator, and Columbia River futurist.

1828: Hall Jackson Kelley, “The Prophet of Oregon”

Hall Jackson Kelley, a Boston schoolteacher, read the journals of Lewis and Clark and saw the light of what would be called Manifest Destiny in about 20 years. Like Thomas Jefferson, Kelley fervently believed it was America’s destiny as a nation to stretch from Atlantic to Pacific.

So he acted. In 1828 he convinced Congress to issue a memorial urging American settlement of the Northwest, which at that time was occupied jointly by the United States and Great Britain. The following year he created the “American Society for Encouraging the Settlement of the Oregon Territory,” and in 1830 he published a pamphlet — one of many on the subject — entitled A Geographical Sketch of that Part of North America called Oregon. Broadly distributed, it proved quite popular. Considering he actually never had been to Oregon, it was an inspired and inspiring piece. Based on the Lewis and Clark journals and his own interviews with Boston merchants, Kelley argued in the pamphlet that America had a right to colonize the Northwest by virtue of Robert Gray’s 1792 discovery of the river — this, too, was unresolved between the United States and Great Britain in 1830, and would be for 16 more years. Kelley described the geography, climate and natural resources of the Northwest in glowing, complimentary and wildly biased detail. For example, he wrote:

Much of the country within two hundred miles of the Ocean, is favorable to cultivation. The valley of the Multnomah [today the Willamette River] is particularly so, being extremely fertile. The advantages, generally, for acquiring property are paramount to those on the prairies of the West, or in any other part of the world.

He even praised the unpraiseworthy arid wastes, suggesting that the windswept, sandy plains around the confluence of the Snake and Columbia rivers were treeless because, although the soil had “great fertility,” Indians burned the trees, and their roots, branches and seeds (“a peculiar and habitual practice”). He planned two communities in Oregon and signed up volunteers to populate them. He promised land grants to his pioneers but had no power to grant them, and neither did the Congress.

Kelley finally did visit Oregon. His 1833-36 expedition arrived there via Mexico and California. A small group of emigrants who had agreed to go with him robbed him instead, and in California he conducted surveys without permission to do so and then recruited a new party for the trip to Oregon. By the time he arrived at Fort Vancouver, word had been received there that Kelley had stolen horses in California. In fact, he had not, but he was not well-received by the British as a result. Nonetheless he conducted surveys and observed the British trading methods — until Dr. John McLoughlin, Chief Factor at the fort, had had enough of him. McLoughlin wrote him a personal check, booked him passage on a ship, and sent him home.

Kelley published a book of his reminiscences and experiences in 1852, but it was little more than a protracted description of his many hardships. He died a hermit a few years later.

Despite his obscure death, Kelley played an important role in Columbia River history, as he was an early and vigorous propagandist. The communities he hoped to establish never formed. But his flamboyant writing, unsinkable optimism and wild enthusiasm for Oregon lit a fire of public interest for westward migration on the Oregon Trail.

1834: Nathaniel Wyeth, Pioneer Columbia River entrepreneur

One of the people Kelley inspired was Nathaniel Wyeth, a Cambridge merchant who visited Kelley in 1829 and came away a believer in the promise of Oregon. He enrolled in Kelley’s effort to colonize Oregon, but then pulled out and formed his own expedition. It’s not clear why, but Wyeth did have different interests. Rather than a colony, Wyeth sought to establish a trading business on the lower Columbia. Salmon and furs were the primary objects of Wyeth’s business enterprise, which he called the Pacific Trading Company.

The Hudson's Bay Company had been salting Columbia River salmon for export for a couple of decades before Wyeth decided to give it a try. He left the East Coast in March 1832 and assembled a party of 24 before he reached St. Louis. They were heavily armed and dressed in identical uniforms of woolen jackets and pantaloons and striped cotton shirts and had a quasi-military appearance. After that, desertions in route and other misfortunes complicated his plans. He arrived at Fort Vancouver in the fall, spent the winter and then returned east to St. Louis in the spring of 1833.

Undeterred, Wyeth believed the Bay Company would leave the Northwest in 1838, when the 10-year joint occupation agreement between America and Great Britain was set to expire. He planned to pick up the business the British would leave behind. He hoped to conduct a fur trade in the Rocky Mountains and, simultaneously, a salmon industry on the Columbia.

In 1834, he came West to try again, this time with 40 employees, 130 horses and a large supply of goods. He also dispatched a supply ship from Boston to meet him on he Columbia. With Wyeth on the land journey were the missionaries Jason and Daniel Lee, the first Christian missionaries to settle in Oregon’s Willamette Valley. En route, Wyeth built Fort Hall on the Snake River at the mouth of the Portneuf River in southeastern Idaho, then moved on to the Columbia where he expected to meet his ship and begin a salmon industry.

But Wyeth — and the ship, the Mary Dacre — did not arrive until September, too late to catch many salmon and pack them that year. So he built a trading post, Fort William, on Wapato Island at the mouth Willamette River, for his renamed enterprise, The Columbia River Fishing and Trading Company. From this base of operation, he explored the Deschutes River in the winter of 1834-35, eventually returning to Fort Hall for the winter of 1835-36 to cache his furs and decide what to do next.

In the spring of 1836 he was back at Fort Vancouver for a final try, but his well-established rival, while friendly, had no intention of letting a competitor succeed. Despite this competition, Wyeth befriended McLoughlin at Fort Vancouver. Competition with the superior company for furs and fish was only one of his problems. His relations with the fur trappers he employed in the mountains were strained, at best, and his salmon business failed because Indians did not bring him fish consistently, and sometimes refused to do so. Historians Dorothy Johansen and Charles Gates suggest this was because the Bay Company ordered them not to: “He had neither the capital nor experience to compete on the one hand with the well-entrenched Hudson’s Bay Company, and on the other with the hardened leaders of the mountain men whom he described as scoundrels,” the historians wrote.

In a word, Wyeth was premature. A salmon industry ultimately would develop on the Columbia, but it would rely on its own fishermen and not primarily on Indians, as Wyeth had. Wyeth discovered that the Indians, while excellent fishers, did not appreciate the importance of curing fish when they were fresh. As well, the Indians had well-established trading relationships with the Hudson’s Bay Company that Wyeth simply could not break. In 1837 Wyeth sold Fort Hall to McLoughlin and the Bay Company then returned to the East for good. Like Kelley, Wyeth raised interest in Oregon but failed to break the hold of the Hudson’s Bay Company.

1859: Lt. John Mullan: Road builder

U.S. Army Lt. John Mullan’s legacy in the Columbia River Basin is the 624-mile wagon road he built from old Fort Walla Walla, at Wallula on the Columbia River, to Fort Benton on the Missouri River in present-day Montana, thus linking the basins of the Columbia and Missouri/Mississippi rivers.

Mullan started from Fort Walla Walla on July 1, 1859 with about 100 men and completed a trail to Fort Benton, via the Coeur d’Alene River valley in present-day Idaho and the St. Regis River valley in Montana, in 1860; the wagon road was completed in the summers of 1861 and 1862.

The road was intended for military purposes, but by the time it was completed the Indian wars in eastern Washington were over. Only a few troops ever used it, and while it had some use during the Montana gold rush of the early 1860s, it soon fell into disrepair over most of its route.

Mullan, however, was one of those people who recognized the great potential of the inland Northwest to support a population and further development. In 1858 he wrote in his journal:

Night after night I have lain out in the unbeaten forests, or on the pathless prairie with no bed but a few pine leaves ... with no pillow but my saddle, and in my imagination heard the whistle of an engine, the whir of the machinery, the paddle of steamboat wheels, as they plowed the waters ... In my enthusiasm I saw the country thickly populated, thousands pouring over the borders to make homes in this far distant land.

Perhaps he saw his road as the major transportation artery to this promised land, but the reality of the road proved to be less exciting than his vision of the future. The Jesuit missionary Father Joseph Cataldo, whose Coeur d’Alene mission was on the road, commented: “The Mullan trail wasn’t much of a road. It was a big job, well done, but we used to say, ‘[Lt.] Mullan just made enough of a trail so he could get back out of here.’”

1883: Sandford Fleming, Canadian railroad surveyor

In the last two decades of the 19th century, the iron horse of the railroad galloped across the plains, prairies and snowy mountain ranges of the United States and Canada, linking the East and west coasts. In railroads were bright promises: Pacific coast metropolises would rise to rival those of the East Coast; trade with the Orient would flourish; fortunes would be made; national economies would prosper; and civilization would expand.

In Canada, the Canadian Pacific Railway pushed in both directions toward the Columbia River — west across Alberta and east up the Fraser River from the recently established coastal city of Vancouver, where the railroad met saltwater. For the westbound effort, in 1882 Major A.B. Rogers blazed a trail west from Kicking Horse Pass in the Rockies down the Kicking Horse River to the north-flowing Columbia where the city of Golden now stands. From there, he crossed the river and went up and over the Selkirk Mountains, meeting the Columbia again — now flowing south — where the city of Revelstoke stands today. It was a daring route, more direct than following the river on its great bend around the Selkirk Mountains, but riskier because it meant building over yet another mountain pass.

George Stephen, president of the Canadian Pacific, wanted an independent assessment of the mountain route before he would approve construction. So in 1883 he called back to service Sandford Fleming, who had been the company’s engineer-in-chief from 1871 to 1880. Having crossed the Rockies at Kicking Horse Pass, where the CPR was building its line, Fleming and his party descended the Kicking Horse River to Rogers’ camp on the Columbia.

It was June, and one Sunday evening, setting aside for the moment the frantic business of building a railroad, Fleming walked to a point about 500 feet above the Columbia to view “the noble landscape,” as he called it. CPR historian Pierre Berton writes that the scene must have been “like painted backdrop — the great river winding its slow way through the forested valley; the evergreen slopes of the foothills rising directly from the water; a line of blue mountains, sharp as sword blades…”

Fleming was a visionary as well as a surveyor and engineer. He saw the great, untapped promise of the Columbia River. Reflecting on the scenery and the challenge ahead for the railroad and Canada, Fleming wrote:

I asked myself if this solitude would be unchanged, or whether civilization in some form of its complex requirements would ever penetrate this region? . . .will the din of the loom and the whirl of the spindle yet be heard in this unbroken domain of nature? It cannot be that this immense valley will remain the haunt of a few wild animals. Will the future bring some industrial development: a future which is now dawning upon us? How soon will busy crowds of workmen take possession of these solitudes, and the steam whistle echo and re-echo where now all is silent? In the ages to come, how many trains will run to and from the sea to sea with millions of passengers?

The railroad was completed in November 1885 with a spike-driving ceremony at Craigellatchie, a few miles west of Revelstoke. As Fleming predicted, the silence of the mountains soon was broken. Towns sprung up along the railroad, and immigrants soon followed. The future Fleming envisioned had dawned.

1889: William Baillie-Grohman, Kootenay/Columbia canal builder

Fifty-one miles (82 kilometers) north of Cranbrook, British Columbia, Provincial Highway 93 crosses the Kootenay River and makes a long, sweeping curve around the southwestern shore of Columbia Lake, the headwaters of the Columbia River. Here in the valley between the Rocky Mountains to the east and the Selkirk Range to the west, where the south-flowing Kootenay and the north-flowing Columbia Lake are 6,000 feet apart, a visionary English entrepreneur imported Chinese laborers to begin digging a canal in 1882 that, when completed in 1889, left the entire 300-mile Selkirk Range surrounded by water — an island, he liked to say, about the size of England.

His name was William Adolph Baillie-Grohman. Half Scottish and half Austrian, son of a Tyrolean countess, he enjoyed traveling the world to hunt big game. The lure of mountain goats and grizzly bears brought him to the Columbia headwaters in 1882, and there he had a vision. The Canadian Pacific Railway’s transcontinental line passed through Golden, downstream to the northon the Columbia. Gold had been discovered downstream to the south at Wild Horse Creek on the Kootenay. Farther downstream on the Kootenay, at Creston, just north of the international border, there was wonderfully rich agricultural land waiting to be exploited if only the periodic floods could be tamed.

And so in the valley between two great rivers, Baillie-Grohman’s grand scheme fell into place: if a canal were built to link the Kootenay with Columbia Lake, the Kootenay could be diverted to an extent that would control flooding downstream at Creston and, at the same time, steamboats could operate along the two rivers between Golden and Jennings, Montana, a distance of some 300 miles. Baillie-Grohman envisioned a prosperous future. He would develop the Kootenay-Columbia canal and the farmland at Creston and become wealthier than he already was. He immediately took his idea to the provincial government, which expressed support.

There was one problem, however. The Canadian Pacific Railway objected, and that was significant opposition in British Columbia the 1880s. The railroad argued that diverting the Kootenay into Columbia Lake could flood the main line at Golden. As well, local farmers worried that the influx from the Kootenay could flood their hay fields. In addition, the federal government, not the province, was in charge of navigable waterways like the Columbia and Kootenay. If the Canadian Pacific objected, it was a near certainty that the federal government would, too. So Baillie-Grohman struck a deal. His syndicate — he had raised money for the land development and the canal company in England — would built the canal, but the level of the Kootenay would be maintained and a lock would be installed and only opened to allow steamships to pass.

The Baillie-Grohman syndicate imported 200 Chinese laborers to build the canal, which was completed in 1889. It was 6,700 feet long and 45 feet wide. The lock was 100 feet long and 30 feet wide.

It was used only three times. The Gwendoline went through from Columbia Lake to the Kootenay in 1893, and made the return trip the following year. The North Star literally blasted its way through in 1902, as it was too wide and too long for the lock. That was an interesting event. Equipment was removed from the sides of the boat so that it would fit, and the end of the lock facing Columbia Lake was extended with sand bags. The boat was floated in, the head end of the lock was dynamited, and the North Star literally sluiced into Columbia Lake. Since then, the remains of the canal have flooded periodically and spilled Kootenay River water into Columbia Lake. Portions of the canal, silted and stagnant, remain visible today.

As for Baillie-Grohman, neither the canal project, nor a sawmill he built at Canal Flats to supply wood for the canal, nor the Creston agricultural promotion, nor his writing on natural resources including Columbia River salmon, were successful enough to keep him in British Columbia, and he eventually returned to Europe. He was a better visionary than businessman or engineer, but he was one of the first visionaries to assert that engineering could tame the wild Columbia. In this sense, his optimism reflected the sense of supreme confidence that accompanied the Industrial Revolution, confidence that engineering could improve the environment, harness it, put it to work. In just a few decades, others also would propose to harness the Columbia through feats of engineering in the construction of large, multipurpose dams.

1915: Sam Hill, promoter of good roads

Sam Hill, builder of the Maryhill mansion in the eastern Columbia River Gorge, son-in-law of James J. Hill, the “Empire Builder” of the Great Northern Railroad, and independently wealthy in his own right, promoted the construction of hard-surface roads and highways to link rural communities to cities. He envisioned good roads not only for purposes of commerce, but also for convenience of long-distance travel and for the pleasure of experiencing natural wonders like the Gorge. With his friend Samuel Lancaster, an engineer, and the help of some of the wealthiest businessmen of Portland, Hill envisioned and ultimately brought to completion the Columbia River Highway through the Gorge.

Born in 1857 in Deep River, North Carolina, Hill’s family moved to Minneapolis when he was 8 years old. He grew up there, attended college in Minnesota and at Harvard for a year as an undergraduate and briefly at the law school, and then returned to Minneapolis to open a law practice. In 1886 he was hired by James J. Hill to work in the legal department of the Great Northern and two years later, in 1888, married Hill’s oldest daughter, Mary Mendanhall Hill.

Sam Hill’s interest in the Northwest began in 1893 when the Great Northern extended tracks to Seattle. Sam Hill visited the sawmill town on the shore of Puget Sound frequently on railroad business and, by 1902 when he moved there permanently, he had been named president of the Seattle Gas and Electric Company, which had been purchased several years earlier by investors in Seattle and Minneapolis.

In 1899, at a time when automobiles were rapidly gaining popularity and becoming more of a necessity of life than an amusement, Sam Hill and a few friends formed the Washington State Good Roads Association; Hill was its president through 1910 and, later, its honorary president for life. He lobbied nationally for good roads beginning in 1900, when he addressed a U.S. Senate committee on the subject. This also was the year of the first National Auto Show. He continued his lobbying for good, hard-surface roads in Washington and across the country as interest grew in improved public transportation and better roads to link rural areas with cities.

In 1906 he met Samuel Lancaster, a civil engineer with extensive experience in siting and building roads and railroads. Lancaster was a consulting engineer for the federal Bureau of Public Roads within the Department of Agriculture. The agriculture secretary, James Wilson, sent Lancaster to meet with Hill at a roads conference in Yakima to discuss the road situation in the state. The two men quickly became friends, and Hill persuaded Wilson to allow Lancaster to stay six months in Washington to help design roads. After the six months, at Hill’s urging Lancaster resigned his federal post to help design a $7 million system of roads and parks for the 1909 Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition in Seattle. Meanwhile, in 1907 Hill helped persuade the regents of the University of Washington to establish a chair of highway engineering — the first in the nation — with Lancaster as its professor in 1908-09.

Hill, as president of the Washington Good Roads Association, represented the state at the International Road Congress in Paris in October 1908. He took Lancaster and Seattle’s city engineer with him, paying their way. The three traveled throughout Europe — it was Hill’s 32nd trip to the continent — inspecting roads. Along the Rhine they saw the rock retaining walls that had been built by Charlemagne to support terraces for vineyards, and Hill told Lancaster that one day similar rock walls would support the road he envisioned through the Columbia River Gorge. Later in an interview with historian Fred Lockley, Lancaster recalled that Hill told him: “We will build a great highway so that the world can come out and see the beauties of the land out of doors . . .and we will realize the magnificence and grandeur of the Columbia River Gorge.”

Hill biographer John E. Tuhy writes that the Columbia River Highway was “the Holy Grail” of Hill’s campaign for good roads. Hill and Lancaster wanted to build a road that would blend into the remarkable scenery of the Gorge, a road that would become a matter of civic pride. Hill convinced the Multnomah County commissioners and the Oregon Legislature to support the project — he even brought the Legislature to Maryhill in February 1913 to view the experimental roads he had built there. Seattle was beginning to eclipse Portland in population and economic importance, and a new road from Tacoma to Mount Rainier was sure to boost tourism. Portland needed the highway through the Gorge.

Rufus Holman, in 1913 a Multnomah County commissioner and later a U.S. senator, called Hill the “playwright and director” of the highway. In an interview after the highway was completed, Holman recalled that he visited the Gorge with Hill in May 1913. There the two men stood on a cliff over the river at sunset and Hill said, “envision for me a wonderful road through that wild canyon. . ..a road such as no one had yet seen.”

The Columbia River Highway from the coast through the Gorge was completed in the summer of 1915, and by November the road was open to Pendleton. The highway was dedicated in June 1916 with a ceremony at Multnomah Falls.

Lancaster and Hill went on to other projects. Lancaster designed a road along the north rim of the Grand Canyon; Hill started construction on his Maryhill mansion, which was only partially completed in his lifetime. He also built a war memorial in the shape of Stonehenge to honor soldiers from Klickitat County, Washington, who died in World War I. The Stonehenge replica is just off U.S. Highway 97 a few miles east of Maryhill.

In 1928, Hill told Lockley: “When the Columbia River Highway was being built and I prophesied that the time would come when, instead of having five- or seven-passenger cars, there would be regular stages and buses, carrying as many as 12 people at a time, to Seattle and to The Dalles and to other points in the state, I was jeered at and called a dreamer and visionary.” It was a prescient comment, for indeed he was a dreamer and visionary, and the Gorge was a special place to him.

Hill died Feb. 26, 1931, in Portland following a brief illness. Two miles west of Crown Point is a memorial to him, dedicated on May 13, 1932, which would have been his 75th birthday. Tuhy comments that while many people stop to read the inscription, “probably few are aware of the effort, determination, and devotion of Sam Hill and others who made their journey an inspiring one.” Hill’s ashes are in a crypt near the Stonehenge memorial.

1918: Rufus Woods, promoter of Grand Coulee Dam

To say Rufus Woods believed in Grand Coulee Dam is to say that fish believe in water. Woods firmly believed the great dam would be as vital, as real, as necessary, and as needed in central Washington as food and water.

For sure, its promise was food and water in the form of the Columbia Basin Project, and also jobs, rural electricity and a better economy long into the future. But first, it had to be built, and if it would be built, it needed a champion.

Rufus Woods was the man.

Woods was the editor and publisher of the Wenatchee World newspaper in that central Washington city on the Columbia River. He was a strident, outspoken supporter of Grand Coulee Dam literally from the moment he heard the idea, and he heard it from his friend Billy Clapp, an attorney in nearby Ephrata. Woods trumpeted the idea in the World. On July 18, 1918, his story and its all-capitals screamer headline ran on Page 7. Here are the headline and the first sentence of the story:

FORMULATE BRAND NEW IDEA FOR IRRIGATION GRANT, ADAMS, FRANKLIN COUNTIES, COVERING MILLION ACRES OR MORE

The latest, newest; the most ambitious idea in the way of reclamation and development of water power ever formulated is now in process of development.

Woods biographer Robert Ficken wrote, in Rufus Woods, The Columbia River, & The Building of Modern Washington (Washington State University Press, 1995), that the fact that such a momentous announcement, even though it lacked details, appeared on Page 7 was “a triumph of haphazard organization over editorial significance.”

The only punctuation missing is the exclamation point — maybe several of them. It wasn’t the first proposal for a dam at the Grand Coulee of the Columbia 123miles upstream from Wenatchee, but the story in Woods’ newspaper that day would be the one that would register with the people of central Washington. It was the story that energized and excited people about the tremendous economic potential that a big dam would create, particularly in a dry country noted for its rich soil, where farmers could gaze down steep canyons to the Columbia 500 or more feet below and dream that even a fraction of its water might be pumped, somehow, to their fields. Grand Coulee Dam was the solution. Historian Paul Pitzer writes that the story that ran that day in the World “did prove to be the genesis of the Grand Coulee Dam idea.”

Woods was born in Nebraska and trained as a lawyer. He arrived in Wenatchee in 1904 and began working as a reporter. In 1907 he bought the World, a Republican newspaper with a small readership and a reputation for dullness. Woods changed that. He once declared that “the providence of the newspaper is much broader than just a concern from which to make money.” A newspaper, he said, “should stand for something.” He wrote his editorials in the first person and sometimes, when he was particularly excited about an issue, used whole paragraphs of capital letters.

He had a lot of fun at the World. He liked to dress in goofy clothes, he drove around in a convertible that featured a portable desk and typewriter — always ready to write. He joked and enjoyed promoting wild ideas as well as legitimate causes in his paper. In 1949, for example, he proposed that Lake Roosevelt behind Grand Coulee Dam be stocked with whales. He was the hero of the little man, and one of his constant editorial drumbeats was the need to free the Northwest from the grip of big corporations and big government.

Woods was a leader of the Progressivism movement in Washington in the teens and ‘20s, and the cause of Grand Coulee Dam and Columbia River development conformed with his progressive and reformist instincts. Industry, agriculture, economic development, self-determination, freedom from East Coast corporate robber barons and faceless big government — all of these benefits were in the promise of the great dam, Woods believed. Against long odds, Woods and a small group of nearly fanatical dam proponents kept the Grand Coulee dream alive through the 1920s, with the World as their organ of propaganda.

Woods and his colleagues, who informally became known as the Dam University, lobbied hard for local control of the Grand Coulee project, but ultimately acquiesced to President Franklin Roosevelt’s Interior Secretary, Harold Ickes, who insisted that the project be federal. Once the dam was built, most of its power was sent to Hanford and the urban area around Portland. The federal Bureau of Reclamation ran the dam, and the power was sold by the Bonneville Power Administration, a federal agency based in Portland. To Woods’ frustration, his dam was built but, with the exception of the Columbia Basin Project, most of its benefit was downriver and the industry he had envisioned near the dam did not materialize.

Woods’ biographer, Robert Ficken, writes: “Although disappointed, Woods was by no means embittered by the frustration of his dreams. The fight for Grand Coulee had been ‘a real drama’ and construction of the dam a ‘miracle.’ With his friends, Rufus had produced, for all its imperfection, ‘something grand, noble, heroic, [and] imposing.’ Unwilling to give up, he continued to rush ‘hither and yon’ on behalf of new development proposals.”

The economic promise of north central Washington remained bright, Woods believed, as long as one kept in mind a fundamental proposition: “let us never forget the importance of water water water.”

1930: Herbert G. West, champion of navigation

In the early 1930s,when advocates of rural electrification and irrigation envisioned the promise of prosperity in the massive Bonneville and Grand Coulee Dams, others envisioned the Columbia and Snake rivers as waterways of commerce from the Pacific Ocean and beyond to their farms. Grand Coulee would irrigate the fertile, dry interior plateau; Bonneville would create a lake — slackwater — that would flood the falls of the Cascades and make barge traffic much easier. With one or two more dams like Bonneville, and with locks big enough for ocean-going vessels — sea locks, they were called — ocean-going freighters might steam all the way to the river towns of the interior and make them port cities.

Inland navigation had a champion in Herbert G. West, who moved from Portland to Walla Walla in 1930. By occupation, West was a salesman, but by avocation he was a promoter and propagandist. Navigation on the Columbia and Snake rivers was his product, and he was its tireless salesman. Eventually, he would be elected mayor of Walla Walla and would be on a first-name basis with many of the region’s most important politicians, most notably U.S. Sen. Warren Magnuson, D-Wash., who provided the political muscle to realize West’s slackwater vision for the lower Snake River, connecting the Inland Empire to Portland and the Pacific Ocean.

West was the first managing secretary of the Inland Empire Waterways Association, a pro-navigation development association that began humbly enough in Walla Walla in 1934. In that year, with construction having begun at Bonneville and Grand Coulee the year before, numerous small, loosely organized and generally uncoordinated local development associations formed throughout the interior Columbia River Basin. Chambers of Commerce in a number of small Snake River towns organized a February meeting in Lewiston to promote the idea of an “open river.” It was billed as an informational meeting, but the night before a small group of men met in Walla Walla — Herbert West among them — to develop the Walla Walla Chamber’s official position to present at the meeting. What emerged was a seven-point proposal that called for sea locks at Bonneville and an open river, among other things, from there to Lewiston, Idaho. The next day the Lewiston delegates listened, but refused to vote on Walla Walla’s bold proposals, and so the Walla Walla group met again and formed an organization to champion their vision — the Inland Empire Waterways Association.

Initially, the IEWA had no greater promise than other development groups, but the IEWA had Herbert West, whom author Keith Peterson has described as “tireless and ruthless in his efforts to build IEWA’s membership.” Soon West was appointed to President Roosevelt’s Natural Resources Committee and also to the Water Resources Committee of the Northwest Regional Planning Commission.

At the same time he was building the IEWA’s political foundation among regional lawmakers, West was building the organization from the ground up with donations from individuals who saw in West the leader who just might accomplish the great things he promised. West built the IEWA into a major political and economic force, meeting with Roosevelt advisor Harold Ickes when he toured the Bonneville Dam construction site. With the IEWA, he promoted river-based commerce when the dam was completed, as he saw success at Bonneville as the first step toward success on the Snake. He allied himself with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the federal agency in charge of building Bonneville and maintaining the navigation channel in the river. The cozy relationship, which would result in many occasions of visible political support — the Corps for the IEWA and the IEWA for the Corps — would endure for decades.

West was nothing if not tenacious in support of dams on the lower Columbia and Snake rivers. His long-term vision remained fixed on slackwater and the vibrant river-based commerce he was certain it would create, and he promoted any aspect of the dams if he saw it might benefit the goals of the IEWA. In the 1930s, he promoted navigation. In the 1940s, when he realized that, politically, the dams would not be authorized by Congress solely for navigation, he promoted their potential hydroelectric benefits. In the 1950s, when he realized fishery interests opposed the dams because of the destruction they might cause to migrating salmon and steelhead, he asserted that modern turbines would not harm fish. He said those who opposed dams on for such reasons were impeding the region’s progress. In May 1952, for example, he wrote to the Columbia River Fishermen’s Protective Association, a gillnetter’s union, “It is high time that the people who are dependent on the fishing industry for their livelihood should stop their blind, unreasoning attacks on progress and development.” In May 1955, he testified before a Congressional subcommittee that tests showed fish could pass the dams “without irreparable damage to the fishery resource.”

It would take decades to realize Herbert West’s vision of an open river to Lewiston. Congress did not authorize the four dams of the Lower Snake River Project until 1945, and it would be another 30 years until Lower Granite Dam, the last of the four projects and the one that finally brought slackwater to Lewiston, would be completed. And it can be argued that if the battle over the four lower Snake River dams had been waged in the 1960s and ‘70s they might not have been authorized because that is when the nation’s sentiment began to turn against dams, and environmental concerns were taken more seriously in Congress than they were during the Depression and post-war boom times of the ‘30s, ‘40s and ‘50s. Nonetheless, without the tenacity and patience of Herbert West, the Lower Snake River Project — the four federal dams — likely would not have happened.

1941: Woody Guthrie, hydropower balladeer

In 1941, folksinger Woody Guthrie, described by his friend Pete Seeger as a political radical who distrusted government, was hired by the government — specifically, the information service of the Bonneville Power Administration in Portland, Oregon — to write songs about a New Deal jobs program that was building two dams on the Columbia River as a venture to make hydropower and sell it at cost to the public. That is, first to the public and then to the privately owned electric utilities, if any power was left over.

The songs were intended to be used in an informational film called The Columbia, a revision of Bonneville’s original 1939 film Hydro. Bonneville hoped The Columbia would have a more approachable, grassroots feel when narrated by Guthrie’s songs.

In desperate need of any kind of job, having left his last radio program in Los Angeles and unable to pay his rent, he said yes, anticipating the power of a regular paycheck (he had a wife and three small children) and the chance to write about something new and potentially powerful for the people. Indeed, although he was a populist who thought government was run by rich people for the benefit of rich people, the idea of a regionwide public power project that was already benefitting those out of work by providing jobs apparently was intriguing. And additionally, the public power project soon would benefit everyone with low-cost electricity, not just the despised rich people. And, of course, there was that paycheck.

He was 28 and popular, if not widely known, as the result of his radio programs and a collection of his Dust Bowl ballads, released the previous year. He arrived at Bonneville Power without a finalized contract, so was only able to get an emergency appointment of 30 days. Guthrie spent that month as a Bonneville employee (May 13 through June 13, 1941) writing; his official title was “information consultant.” During this time he toured Hood River, Oregon, and Bonneville and Grand Coulee dams and saw people working at the dams and the places that would be irrigated by the Columbia Basin Project with water from Grand Coulee, which was completed that year. New to the beauty of the Pacific Northwest, he was inspired. He typed lyrics at a desk at Bonneville and at his apartment and recorded 26 songs with his guitar in a tiny converted utility room that he described as “a clothes closet there at the Bonneville Power administration house” in Portland. He was paid a total of $266.66 (about $5,000 in 2021 dollars). Some songs were new and some old with new lyrics, but he tapped out nearly a song a day. The Columbia film was postponed after the United States entered World War II and was not completed until 1949, when an ending featuring the Vanport flood finally was written and filmed. Another of Guthrie’s greatest songs, “Pastures of Plenty” is also a part of this canon. The song ties together migrants en route to Oregon for work in the fruit orchards, workers building the dams, and the plight of all workers whoever and wherever they are, and is used very effectively in the final film.

Collectively, the remarkable songs defined the government’s grand experiment in making power for the people. One song in particular, “Roll on, Columbia, Roll On,” became a Northwest anthem and Washington state’s official folk song. In just a few simple words about the rolling river and its power, the chorus of that song captures the promise of Columbia River hydropower to light rural homes, provide jobs and improve lives. In other songs, he needled the critics who believed Grand Coulee Dam was a colossal waste of money and electricity in a remote and sparsely populated region.

Bill Murlin, a former Bonneville Power Administration information officer, collected and edited the songs for a publication that was issued by the U.S. Department of Energy in 1987 to honor Bonneville’s 50th anniversary. To Murlin, Guthrie’s songs are part of the heritage of the Pacific Northwest. They are a source of special pride to Northwesterners, wherever they live, he said at the time, adding: “because of Woody, people who have never seen the Columbia River sing about it.”

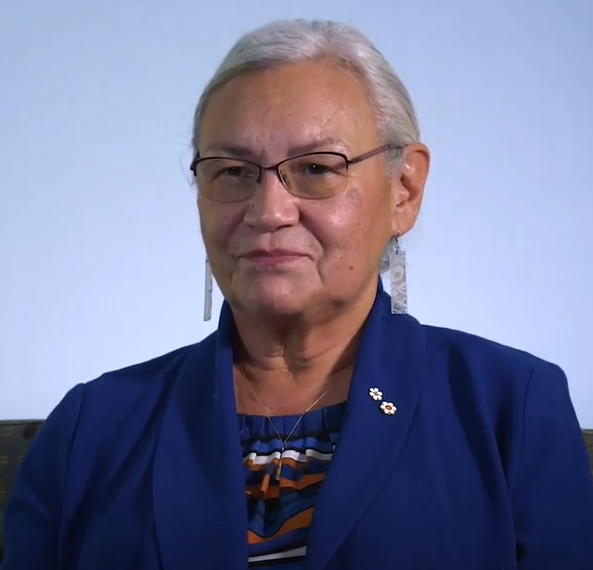

1993: Sophie Pierre: Canadian Columbia River salmon advocate

Sophie Pierre, a chief of the Ktunaxa-Kinbasket Nation, whose homeland includes the headwaters of the Columbia and the upper Kootenay River, envisions a united effort of First Nations to focus on rebuilding the salmon and steelhead runs that were lost to Grand Coulee Dam. At a salmon conference in Vernon, British Columbia, in October 1993, she put her vision in perspective:

That mighty Columbia River starts right in the heart of our Ktunaxa homeland. And it’s not just the Ktunaxa that have the Columbia as a homeland. We have that in common with the Shuswap and the Okanagan. When this river was being so dramatically impacted and the resources so indiscriminately destroyed, these three nations of people were not considered. It was like we didn’t even exist. Wasn’t that the real point? We were not supposed to exist, at least not very much longer.

As I was growing up, I learned an aboriginal teaching: Everything in life comes a full circle. There is nothing you do that does not come back to you. The destruction on the Columbia has come back full circle, where we come back to the point that we are looking at the restoration of this great river. Speaking from an aboriginal perspective, I know, and you know, that river will never be exactly the same as it was. There are too damn many dams on that river, and we are too dependent on that [hydroelectric] power.

So what we’re talking about is the optimum restoration possible of those species that can survive and thrive in a Columbia River that is at its optimum quantity and quality. We’re talking about bringing that river back to life. Bringing it back full circle.

Salmon may yet return to the Canadian Columbia River. If they do, it will be through the collaborative efforts of Indian tribes on both sides of the border, as well as provincial, state and federal fish and wildlife agencies. The primary obstacle is fish passage at Grand Coulee. The technology is available; what’s lacking is money, agreement and resolve to make it happen.

Pierre, who retains a leadership position with the band, continues to do her part on behalf of the fish and her community. In 2007, 14 years after she spoke on behalf of salmon restoration at the Vernon conference, the Canadian Columbia River Intertribal Fisheries Commission (CCRITFC), which includes Ktunaxa bands in its membership, was moving ahead with an effort to study the feasibility of reintroducing salmon above Chief Joseph and Grand Coulee dams. The CCRITFC retained ESSA Technologies Ltd., a Vancouver, B.C., consulting firm, to prepare a study addressing the myriad social, economical, legal, political, and environmental/biological issues that would have to be addressed if reintroduction were pursued. Earlier, in April 2003, the CCRITFC petitioned the International Joint Commission to take up the matter by revisiting its 1941 Order of Approval for the construction of Grand Coulee, but in October 2006 the IJC declined and recommended the CCRITFC raise the matter with Canada's Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade (DFAIT). ESSA planned to issue its feasibility report in the spring of 2007. Meanwhile, by early 2007, DFAIT had not indicated whether it would take up the matter.

2001: Senator Mark O. Hatfield, prophet of public service

In the history of the Columbia River Basin there are many outstanding political leaders, men and women who envisioned a better future for the Northwest by putting the river to work to electrify homes and farms, provide low-cost power to industries, irrigate crops, control the river’s periodic floods and create a waterway of commerce that would connect the inland Northwest with lower-river ports and the rest of the world. Without their vision and leadership, the benefits would not have been realized.

One of these leaders is Sen. Mark Hatfield, who served in the Senate for 30 years and before that was governor of Oregon for two terms. He has been called the moral conscience of the Senate for his outspoken advocacy of human rights, nuclear disarmament, the peaceful resolution of international conflicts and improvements in health care, education and social services. He was a critic of the effort to build nuclear power plants in the Northwest because of their high cost compared to the region’s hydropower, and the uncertainty and danger of nuclear waste storage and disposal.

To Hatfield, completing the Columbia River hydropower system in the mid-1970s, and reaping its benefits to this day, shouldn’t be the end of the Columbia River hydropower story. The hydropower system delivers tremendous benefits to the Northwest in the form of navigation, recreation, flood control, irrigation and low-cost electricity. The hydrosystem took a toll on fish and wildlife, but Congress passed the Northwest Power Act in 1980 to address those impacts. Hatfield played a key role in writing the act and shepherding it through Congress. As a longtime critic of nuclear power, he was responsible for the provisions in the act that treat energy conservation as a resource the same as electricity generating plants.

Now, 21 years after Congress passed the act, Hatfield believed it was time to think about the future, and the benefits our society receives from the dams. In 2018, when Bonneville’s debt from the Hydro-Thermal Power Program is finally repaid, some $500 million per year that currently pays for one completed nuclear plant and two that never were built, suddenly will be available. When the debt is retired, (it accounts for more than 30 percent of the rates charged by Bonneville for its electricity), Bonneville either could reduce its electricity rates or it could leave rates where they are and direct the money to programs that would benefit society. Hatfield prefers the latter, and he has some specific ideas.

In a speech to a Columbia River conference in 2001, Hatfield pointed out that the hydrosystem was developed to deliver social benefits — rural electrification, primarily — and that if Northwesterners hoped to retain the benefits of the system it was time to start thinking about what new benefits the system might deliver in the future. At the time, Hatfield was retired from the Senate. Some members of Congress from the Midwest and East Coast thought it was time for the nation to take over the Columbia River system of federal dams and spread the low-cost power to a broader area. Hatfield’s advice: Stop focusing on protecting the power system and begin thinking about how to make it even more valuable to the Northwest. Not only would the region benefit, but the system would be protected from takeover.

He said the hydrosystem has been the envy of the rest of the nation for years because, in simple terms “it’s just plain human nature to covet what you can’t have.” With investments in new technologies, like wind turbines and fuel cells, and with renewed interest in energy conservation, the region could build a power system that, in combination with the dams, would be the envy of the region for its environmental benefits as well as its low cost. But more important, with some creative thinking, the power system could return to its future, in a sense, by focusing new attention on providing social benefits. Electrifying the rural areas in the 1930 and ‘40s and providing electricity to all at its cost of production were economic ideals, but they also were social ideals, and they had profound social benefits for the Northwest.

“Other than Bonneville’s commitment to fund fish and wildlife and other environmental programs, what social purposes are we fighting for today?,” Hatfield asked in his conference speech. “Not rural electrification. We did that. Not further expansion of federal irrigation and farming. That’s unlikely. In other words, not the social purposes of 60 years ago. To guarantee the long-term viability of the system, we must discover new social benefits and pursue their fulfillment as fervently as earlier generations pursued theirs,” he said, adding, “This requires fresh thinking.”

Hatfield was thinking about modern problems: hunger, education, affordable health care, inadequate science and medical research, to name a few. “By tackling these with the revenues generated by Bonneville, we find the ultimate purpose for which we seek to protect the system,” he said. “Many of you may be shocked by this suggestion, but using the benefits of this great energy machine to attack today’s most serious problems in society is the single most effective way to preserve the benefits of the system.”

Redirecting the nuclear debt in this way would forge new and vital links with a broad range of interests, including social service advocates, teachers’ unions, school boards, the medical community and others, he said. “As always with this self-financing power system, the benefits we enjoy are the benefits we pay for when we buy power from Bonneville. If there is a silver lining to the WPPSS nuclear debacle, this is it. The hundreds of millions of dollars spent every year on debt service should not be halted once it is repaid, but diverted to programs that actually have a positive, lasting impact on human lives,” he said.

Hatfield admitted it would not be an easy change to make. It would require statutory changes and, most important, the commitment of the region’s political leaders and Bonneville to leave the power rates unchanged and create a mechanism for receiving and distributing the enormous annual block of money for social purposes. “If we are serious about protecting the benefits of the power system for future generations, we must once again require the system to serve the people — all the people — because it’s the right thing to do both morally and politically,” he said. “Opportunities to make large-scale, meaningful improvements in the lives of disadvantaged people come seldom in a lifetime.”

As his final words echoed off the conference room walls, the audience of several hundred people responded with the polite applause befitting a bombshell idea. One person, and only one, rose to give him a standing ovation. Some, I’m sure, in their minds were jumping to their feet, pumping the air with their fists and cheering wildly. But they didn’t want to make such a statement in front of their peers. Similarly, others, I’m sure, in their minds were boiling because this visionary ex-politician, whom they had considered a friend until this day, would have the audacity to say power rates should do anything but come down in the future. But there was no outward cheering or cursing, only applause that ended rather quickly.

Hatfield smiled, nodded his acknowledgment, and took his seat. He’d been invited to discuss how to preserve the benefits of the Columbia River power system, a system that Northwesterners pay for through their electricity rates, and he had delivered a message that clearly made some in the audience squirm. Imagine, forgoing the opportunity to reduce power rates in favor of, what? Social purposes? The opportunity to reduce hunger, improve education, heal the sick and fight poverty? With electricity revenues?

It was vintage Hatfield.